27

CHAPTER II.

CLASS WAR SKIRMISHES

“Shingle-weaving is not a trade; it is a battle. For ten hours a day the sawyer faces two teethed steel discs whirling around two hundred times a minute. To the one on the left he feeds heavy blocks of cedar, reaching over with his left hand to remove the rough shingles it rips off. He does not, he cannot stop to see what his left hand is doing. His eyes are too busy examining the shingles for knot holes to be cut out by the second saw whirling in front of him.

“The saw on his left sets the pace. If the singing blade rips fifty rough shingles off the block every minute, the sawyer must reach over to its teeth fifty times in sixty seconds; if the automatic carriage feeds the odorous wood sixty times into the hungry teeth, sixty times he must reach over, turn the shingle, trim its edge on the gleaming saw in front of him, cut out the narrow strip containing the knot hole with two quick movements of his right hand and toss the completed board down the chute to the packers, meanwhile keeping eyes and ears open for the sound that asks him to feed a new block into the untiring teeth. Hour after hour the shingle weaver’s hands and arms, plain, unarmored flesh and blood, are staked against the screeching steel that cares not what it severs. Hour after hour the steel sings its crescendo note as it bites into the wood, the sawdust cloud thickens, the wet sponge under the sawyer’s nose, fills with fine particles. If ‘cedar asthma,’ the shingle weaver’s occupational disease, does not get him, the steel will. Sooner or later he reaches over a little

28

too far, the whirling blade tosses drops of deep red into the air, and a finger, a hand or part of an arm comes sliding down the slick chute.”[2]

This description of shingle weaving was given by Walter V. Woehlke, managing editor of the Sunset Magazine, in an article which had as its purpose the justification of the murders committed by the Everett mob, and it contains no over-statement. Shingle weavers are set apart from the rest of the workers by their mutilated hands and the dead grey pallor of their cheeks.

“The nature of a man’s occupation, his daily working environment, marks in a large degree the nature of the man himself, and cannot help but mold the early years, at least, or his economic organization. Men who flirt with death in their daily calling become inured to physical danger, they become contemptuous of the man whose calling fails to bring forth physical prowess. So do they in their organizations become irritated and contemptuous at the long-drawn-out process of bargaining, the duel of wits and brain power engaged in by the more conservative organizations to win working concessions. Their motto becomes ‘Strike quick and strike hard,’* * *” So says E. P. Marsh, President of the Washington State Federation of Labor, in speaking of the shingle weavers.[3]

Logging, no less than shingle weaving, is a dangerous occupation. The countless articles of wood in every-day use have claimed their toll of human blood. A falling tree or limb, a mis-step on the river, a faulty cable, a weakened trestle; each may mean a still and mangled form. Time and again the loggers have organized to improve their working conditions only to find themselves beaten

29

or betrayed. Playing upon the natural desire of the woodsmen for organization, shrewd swindlers have formed unions which were nothing more than dues collection agencies. Politicians have fathered organizations for their own purposes. Unions built by the men themselves have fallen into the hands of officials who used them for selfish personal gain. Over and over the employers have crushed the embryonic unions only to see them rise again with added strength. Forced by the very necessities of their daily lives, the workers always returned to the fight with a new and better form of unionism.

Like the loggers, the shingle weavers were routed time and again, but their spirit never died. The Everett shingle weavers formed their union as a result of a successful strike in 1901. In 1905 they were strong enough to resist a proposed reduction of wages. In 1906 they struck in sympathy with the Ballard weavers, and lost. Within a year the defeated union was back as strong as before. By 1911 the International Shingle Weavers Union had attained a membership of nearly 2,000, the majority of whom were in accord with the Industrial Workers of the World. The question of affiliation with the I. W. W. was widely discussed and was only prevented from going to a referendum vote by the efforts of a few officials. Further discussion of the question was excluded from the columns of their official organ, “The Shingle Weaver,” by the Ninth Annual Convention.[4]

Following this slap in the face, the progressive members quit the union in large numbers, leaving affairs in the hands of conservative and reactionary elements. Endeavors were made to negotiate contracts with the employers; and in 1913 the officials secured $30,000 from the American Federation of Labor and made a pretense at the organization of all workers in the woods and mills into one body. This was a move aimed at the Forest and Lumber

30

Workers of the I. W. W., which was feared alike by the employers and the craft union officials because of its new strength gained thru the affiliation of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers in the southern states. Instead of gaining ground by the move, the shingle weavers union lost in membership and subsequently claimed that industrial unionism was a failure in the lumber industry.

The industrial depression of 1914-15 found all unions in bad shape. Employers used the army of unemployed as an axe to cut wages. In the spring of 1915 notice of a wage reduction was posted in the Everett shingle mills. The weavers promptly struck. Scabs, gunmen, injunctions, and violence followed. The strike failed, the wage reduction was made, but the men returned to work relying upon a “gentlemen’s agreement” that the employers would voluntarily raise the wages of the shingle weavers when shingles again sold for what they were bringing before the depression. Faith in agreements had gotten in its deadly work; the shingle weavers believed that the employers meant to keep their word.

In the spring of 1916 shingles soared to a price higher than had prevailed for years, but the promised raise failed to materialize. With but a skeleton of an organization to back them, a handful of determined delegates met in Seattle in April and decided to demand the restoration of the 1915 scale thruout the entire jurisdiction of the Shingle Weavers’ Union, setting May 1st as the date when the raise should take effect.

At the time set, or shortly thereafter, most of the mills in the Northwest paid the scale. Everett, where the employers had given their “word of honor,” refused the strikers’ demand. The fight was on! The Seaside Shingle Company, which held no membership in the Commercial Club, soon granted the raise. Many of the other companies, notably the Jamison Mill, began the importation of scabs within the month. The cry of “outside agitators” was forgotten long enough to go outside in search of

31

notorious gunmen and scab-herders. The slums, the hells of Capitalism, were raked with a fine-toothed comb for degenerates with a record for lawless deviltry. The strikers threw out their picket line and the ever-present class war began to show itself in other than peaceful ways.

During May, June and July the picket line had to be maintained in the face of strong opposition by the local authorities who were the pliant tools of the lumber trust. The ranks of the pickets were constantly being thinned by false arrest and imprisonment on every charge and no charge, until on August 19th there were but eighteen men on the picket line.

On that particular morning the Everett police searched the little handful of pickets in front of the Jamison Mill to make sure that they were unarmed, and when that fact was determined, they started the men across the narrow trestle bridge that extended over an arm of the bay. When the pickets were well out on the bridge, the imported thugs, some seventy in number, personally directed and urged on by their employer, Neil Jamison, poured in from either side, leaving no means of escape save that of making a thirty foot leap into the deep waters of the bay, and with brass knuckles and blackjacks made an attack upon the defenseless weavers. The pickets were unmercifully beaten. Robert H. Mills, business agent of the Shingle Weavers’ Union, was knocked down by one of the open-shop thugs and kicked in the ribs and face as he lay senseless in the roadway. From a vantage point, thoughtfully removed from the danger zone, the police calmly surveyed the scene.

When darkness fell that night, the pickets, aided by irate citizens, returned to the attack with clubs and fists. The tables were turned. The “moral heroes” had their heads cracked. Seeing that the scabs were thoroly whipped, the “guardians of the peace” rushed to the rescue with drawn revolvers. In the melee one union picket was shot thru the leg.

32

About ten nights later, Mr. Jamison herded his scabs into military formation and after a short parade thru the main streets led them to the Everett Theater; the party being in appreciation of their “efficiency.” This arrogant display incensed the strikers and citizens, and when the scabs emerged from the show a near-riot occurred. Mills was present and altho too weak from his recent injuries to have taken any active part in the fray, he was arrested and thrown in jail in default of bail. The man who had murderously assaulted him at the mill swore out the complaint. Mills was subsequently tried and acquitted on a charge of inciting to riot. Nothing was done to his assailant. And in none of these acts of violence was the I. W. W. in any way a participant.

During this period there existed a strike of longshoremen on the entire Pacific Coast, including the port of Everett. The wrath of the employers fell heavily upon the Riggers and Stevedores because that body was not in sympathy with the idea of craft contracts or agreements, and because of the adoption by a large majority of a proposal to “amalgamate all the unions of the Maritime Transportation Industry, between the Warehouse at the Shipping Point and Warehouse at the Receiving Point into one big powerful organization, meeting, thinking, and acting together at all times.”[5]

The industrially united employers of the Pacific Coast did not relish the idea of the workers grouping themselves together along lines similar to those on which the owners were associated. The longshoremen’s strike started on June 1st and was marked by more or less serious disorders at various points, most of the violence being precipitated by detectives placed in the unions by the employers. The tug boat men were also on strike in Everett, particularly against the American Tug Boat Company owned by Captain Harry Ramwell. All of the unions on strike in Everett were affiliated with the A. F. of L. Striking longshoremen from Seattle aided the shingle weavers on their picket line from time to time, and individual members of the I. W. W., holding duplicate cards in the A. F. of L. stood shoulder to shoulder with the strikers, but officially the I. W. W. had no part in any of the strikes.

33

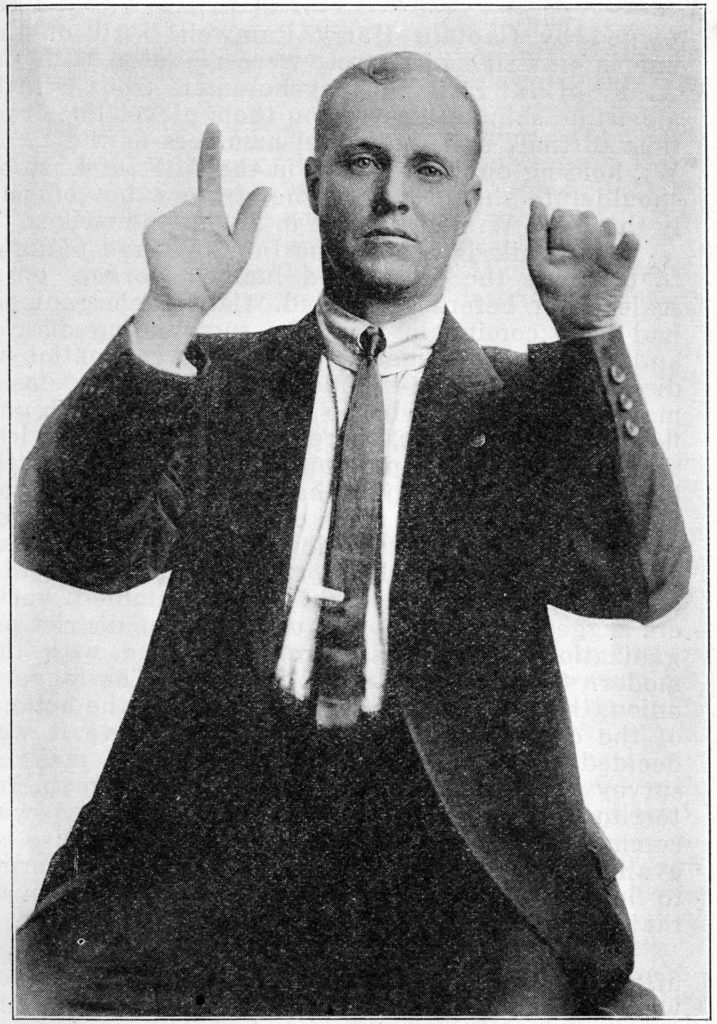

One of the thousands who donate their fingers to the Lumber Trust. The Trust compensated all with poverty and some with bullets on November 5, 1916.

34

Meanwhile in Seattle the I. W. W. had planned to organize the forest and lumber workers on a scale never before attempted. Calls for organizers had been coming in from the surrounding district and there were demands for a mass convention to discuss conditions in the industry. Yet, strange as it may seem to those who do not know of the ebb and flow of labor unions, there were at that time less than half a hundred paid-up members in the Seattle loggers branch, so great had been the depression from 1914 to 1916. The conference was set for July 4th and five hundred logger delegates responded, representing nearly as many camps in the district. Enthusiasm ran high! The assembled workers suggested the adoption of a plan of district organization along lines more in keeping with the modern trend of the lumber industry. The loggers’ union, then known as Local 432, ratified the actions of the conference. As a preliminary move it was decided that an organizer be secured to make a survey of the lumber situation in the surrounding territory. General Headquarters in Chicago was communicated with, James Rowan was found to be available, and on July 31st he was sent to Everett to find out the sentiment for industrial unionism at that point.

That night Rowan spoke on Wetmore Avenue fifty feet back from Hewitt Avenue, in compliance with the street regulations. No mention was made of local conditions as Rowan had just come from another part of the country and was unaware that a shingle weavers strike was in progress. His speech consisted mainly of references to the Industrial Relations Commission Report, a pamphlet

35

summarizing that report being the only literature offered for sale at the meeting. Toward the end of his speech Rowan declared:

“The A. F. of L. believes in signing agreements with the employers. The craft unions regard these contracts as sacred. When one craft goes on strike the others are forced to remain at work. This makes the craft unions scab on each other.”

“You are a liar!” cried Jake Michel, an A. F. of L. representative, staunchly defending his organization.

From an automobile near the edge of the crowd, Donald McRae, Sheriff of Snohomish County, called to Michel:

“Jake, I will run that guy in if you say so.”

“I don’t see any need to run him in;” remonstrated Michel. “He hasn’t said anything yet to run him in for.”

Nevertheless McRae, usurping the powers of the local police department, made Rowan leave the platform and go with him to the county jail. McRae was drunk.

Rowan was held for an hour. Immediately upon his release he returned to the corner to resume his speech. Police Officer Fox thereupon arrested him and took him to the city jail. He was thrown into a dark cell for refusing to do jail work, was taken into court next morning and absurdly charged with peddling without a license, was denied a jury trial, refused a postponement, not allowed a chance to secure counsel, and was sentenced to thirty days imprisonment with an alternative of leaving town. No ordinance against street speaking at Wetmore and Hewitt then existed. Rowan chose to leave town. No time was set as to how long he was to remain away. He then left for Bellingham and from there went to Sedro-Woolley. Using an assumed name to avoid the blacklist he worked at the latter place for a short time to familiarize himself with job conditions, subsequently returning to Everett.

Levi Remick, a one-armed veteran of the industrial war, was next sent to Everett on August 4th

36

to act as temporary delegate. He interviewed a number of people and sold some literature. Receiving orders to stop selling the pamphlets and papers, he inquired the price of a peddler’s license and finding it prohibitive he returned to Seattle to secure funds to open an office. A small hall was found at 1219½ Hewitt Avenue, a month’s rent was paid, and on August 9th Remick placed a sign in the window and started to sell literature and transact business for the I. W. W.

The little hall remained open until late in August. Migratory workers, strikers, and citizens generally, dropped in from time to time to ask about the organization or to purchase papers. Solidarity and the Industrial Worker were particularly in demand, the latter paper having commenced publication in Seattle on April 1st, 1916. A number of Everett citizens, desiring to hear a lecture by James P. Thompson, who had spoken in Everett without molestation in 1915 and in March and April of 1916, made donations to Remick sufficient to cover all expenses, and it was arranged that Thompson speak on August 22nd. Attempts to secure a hall met with failure; the halls of Everett were closed to the I. W. W. The conspiracy against free speech and free assembly was on in earnest! No other course was left but to hold the proposed meeting on the street, so Hewitt and Wetmore, the spot where the Salvation Army and various religious and political bodies spoke almost nightly, was selected and the meeting advertised.

Early in the morning on the day before the scheduled meeting, Sheriff McRae, commanding a body of police officers over whom he had no official control, stormed into the I. W. W. hall and tore from the wall all bills advertising Thompson’s meeting, saying with an oath:

“That man won’t be allowed to speak in Everett!”

Turning to Remick and throwing back his coat to display the badge, he yelled:

37

“I order you out of this town! Get out by afternoon or you go to jail!”

McRae was drunk. Stalking out as rapidly as his condition would permit he staggered down the street to a near-by pool hall where the order was repeated to the men assembled therein. These, with other workingmen, 25 in all were rounded up, seized, roughly questioned, searched, and all those who had no families or property in Everett were forcibly deported. That night ten more were taken from the shingle weaver’s picket line and sent out of town without due process of law. Treatment of this kind became general.

“Not a man in overalls is safe!” declared the secretary of the Everett Building Trades Council. “Men just off the job with their pay checks in their pocket have been unceremoniously thrown out of town just because they were workingmen.”[6]

Remick closed the little hall and left for Seattle the next morning to place the question of the Thompson meeting before the Seattle membership. Shortly before noon Rowan, who had just returned to Everett, went to the hall and finding it closed and locked he proceeded to open it up. Within a few minutes Sheriff McRae, in company with police officer Fox, entered the place and ordered Rowan to leave town by two o’clock. He then tore up the balance of the advertising matter for the Thompson meeting. McRae was drunk. Rowan went to Seattle, where the report of this occurrence made the members more determined than ever to hold the meeting that night.

With about twenty other members of the I. W. W., Thompson went to Everett. The Salvation Army was holding services on the corner. Placing his platform even further back from the street intersection Thompson waited until the Army had concluded and then commenced his lecture. Using the Industrial Relations Commission Report as the basis

38

of his talk, he spoke for about twenty minutes without interruption. Then a body of fifteen policemen marched down the street and swung into the crowd. The officer in charge stepped up to Thompson and requested him to go to see the chief of police at the police station. After addressing a few remarks to the crowd Thompson withdrew from the platform. His place was taken at once by Rowan, who was immediately dragged from the stand and turned over to the same officer who had charge of Thompson and his wife. Mrs. Edith Frennette then spoke briefly and called for a song. The audience responded with “The Red Flag,” but meanwhile Mrs. Frennette and Mrs. Lorna Mahler had been placed under arrest. In succession several others attempted to speak but were pulled or pushed off the stand. The police then formed a circle by holding hands around those who were close to the platform. One by one the citizens were allowed to slip outside the “ring-around-a-rosy” until only “desperadoes” were left. These made no effort to resist arrest, and were started toward the city jail. The officer entrusted with Thompson was so interested in his captive that Rowan was able to quietly remove himself from the scene, returning to the street corner where he spoke for more than half an hour before being rearrested.

Aroused by this invasion of liberty, Mrs. Letelsia Fye, an Everett citizen, arose to recite the Declaration of Independence, but even that proved too revolutionary for the tools of the lumber trust. A threatening move on the part of the police brought back the thought of her two unprotected children and caused her to cease her efforts to declare independence in Everett.

“Is there a red-blooded man in the audience who will take the stand?” called out the gallant little woman as she stepped from the platform. Jake Michel promptly accepted the challenge and was as promptly suppressed by the police at the first mention of free speech.

In the jail the arrested persons were searched one by one and thrown into the “receiving tank.”

39

When Thompson’s turn came, Commissioner of Public Safety, as Chief of Police Kelly was known under Everett’s form or government, said to him:

“Mr. Thompson, I don’t want to lock you up.”

“That’s interesting,” replied Thompson. “Why have you got me down here?”

“We don’t want you to speak on the street at this time.”

“Have you any ordinance against it, that is, have I broken any law?” enquired Thompson.

“Oh no, no. That isn’t the idea,” rejoined Kelly. “We have strikes on, labor troubles here, and we don’t want you to speak here at all. You are welcome at any other time, but not now.”

“Well,” said Thompson, “as a representative of labor, when labor is in trouble is the time I would like to speak, but I am not going to advocate anything that I think you could object to.”

“Now, Thompson,” said Kelly, “if you will agree to get right out of town I will let you go. I don’t want to lock you up.”

“Do you believe in free speech?” asked Thompson.

“Yes.”

“And I am not arrested?”

“No, you are not arrested.”

“Come up to the meeting then,” Thompson said with a smile, “for I am going back and speak.”

“Oh no, you are not!”—and Kelly kind of laughed. “No, you are not!”

“If you let me go I will go right up to the corner and speak, and if you send me out of town I will come back,” said Thompson emphatically. “I don’t know what you are going to do, but that’s how I stand.”

“Lock him up with the rest!” was the abrupt reply of the “Commissioner of Public Safety.”

At this juncture James Rowan was brought in from the patrol wagon, and searched. As the officers were about to put him in the cell with the others, Sheriff McRae called out:

40

“Don’t put him in there, he is instigator of the whole damn business. Turn him over to me.” He then took Rowan in his automobile to the county jail and threw him in a cell, along with B. E. Peck, who had previously been given a “floater” out of town for having spoken on the street on or about August 15th. McRae was drunk.

More than half a thousand indignant citizens followed the twenty-one arrested persons to the jail, loudly condemning the outrage against their constitutional rights. Editor H. W. Watts, of the Northwest Worker, a union and socialist paper published in Everett, forcibly expressed his opinion of the suppression of free speech and was thereupon thrown into jail. Fearing a serious outbreak, Michel secured permission to address the people surrounding the jail. The crowd, upon receiving assurances from Michel that the men would be well treated and could be seen in the morning, quietly dispersed and returned to their homes.

The free speech prisoners were charged with vagrancy on the police blotter, but no formal charge was ever made, nor were they brought to trial. Next morning, Thompson and his wife, who had return tickets on the Interurban, were deported by rail, together with Herbert Mahler, secretary of the Seattle I. W. W. Mrs. Mahler, Mrs. Frennette and the balance of the prisoners were taken to the City Dock and deported by boat. At the instigation of McRae, and without a court order, the sum of $13. was seized from the personal funds of James Orr and turned over to the purser of the boat to pay the fares of the deportees to Seattle. Protests against this legalized robbery were of no avail; the amount of the fares was never repaid. Mayor Merrill of Everett, replying to a letter from Mahler, promised that this money would be refunded to Orr. His word proved to be as good as that of the Everett shingle mill owners. Prominent members of the Commercial Club lent civic dignity to the deportation by their profane threats to use physical force in the event that any of the deported prisoners dared to return.

41

Upon their arrival in Seattle the deported men conferred with other members of the union, telling of the beating some of them had received while in jail, and as a result there was organized a free speech committee composed of Sam Dixon, Dan Emmett and A. E. Soper. Telegrams were then sent to General Headquarters, to Solidarity and to various branches of the organization, notifying them of what had happened. At a street meeting that night, Mrs. Frennette, Mrs. Mahler and James P. Thompson, gave the workers the facts and collected over $50.00 for the committee to use in its work. In Everett the Labor Council passed a resolution stating that the unions there were back of the battle for free speech and condemning McRae and the authorities for their illegal actions. The Free Speech Fight was on!

Remick, in the meantime, had returned to Everett and found that all the literature had been confiscated from the hall. The day following his return, August 24th, Sheriff McRae blustered into the hall with a police officer in his train. Leering at Remick he exclaimed:

“You God damn son of a b——, are you back here again? Get on your coat and get into that auto!”

Seizing an I. W. W. stencil that was lying on the table he tore it to shreds.

“If anybody asks who tore that up,”—bombastically—”tell them Sheriff McRae tore it!”

Shoving Remick into the automobile with the remark that jail was too easy for him and they would therefore take him to the Interurban and deport him, the sheriff drove off to make good his threat. McRae was drunk.

On the corner that night, Harry Feinberg spoke to a large audience and was not molested. That this was due to no change of policy on the part of the lumber trust tools was shown when secretary Herbert Mahler went to Everett the following day in reference to the situation. He was met at the depot by Sheriff McRae who asked him what he had come to Everett for. “To see the Mayor,” answered

42

Mahler. “Anything you have to say to the Mayor, you can say to me,” was McRae’s rejoinder. After a brief conversation Mahler was deported to Seattle by the same car on which he had made the trip over. McRae was drunk.

F. W. Stead reopened the hall on the 26th and managed to hold it down for a couple of days. Three speakers appeared and spoke that night. J. A. MacDonald, editor of the Industrial Worker, opened the meeting. George Reese spoke next, but upon commencing to advocate the use of violence he was pulled from the platform by Harry Feinberg, who concluded the meeting. No arrests were made.

It was during this period that Secretary Herbert Mahler addressed a letter to Governor Ernest Lister, informing him of the state of lawlessness existing in Everett. A second letter was sent to Mayor Merrill and in it was enclosed a copy of the letter to Lister. No reply was received to the communication.

For a time following this there was no interference with street meetings. Feinberg spoke without molestation on Monday night and Dan Emmett opened up the hall once more. On Tuesday evening, the same night as the theater riot, Thompson addressed an audience of thousands of Everett citizens, giving them the facts of the arrests made the previous week, and advising the workers against the use of violence in any disputes with employers.

After having been held by McRae for eight days without any commitment papers, Rowan was turned over to the city police and released on September 1st. He returned to the street corner and spoke for several succeeding nights including “Labor Day” which fell on the 4th. Incidentally he paid a visit to the home of Jake Michel and, after industrial unionism was more fully explained, Michel agreed that the craft union contract system forced scabbery upon the workers. Rowan left shortly thereafter for Anacortes to find out the sentiment for organization in that section.

This period of comparative peace was due to the fact that the lumber barons realized that their

43

actions reflected no credit upon themselves or their city and they wished to create a favorable impression upon Federal Mediator Blackman who was in Everett at the request of U. S. Commissioner of Labor Wilson. It was during this time, too, that the protagonists of the open shop were secretly marshalling their forces for a still more lawless and brutal campaign.

Affairs gradually slipped from the hands of the Everett authorities into the grasp of those Snohomish County officials who were more completely dominated by the lumber interests.

“Tom,” remarked Jake Michel one day to Chief of Police Kelley, “it seems funny that you can’t handle the situation.”

“I can handle it all right,” replied Kelley, bitterly, “but McRae has been drunk around here for the last two or three weeks and he has butted into my business.”

It was on August 30th that the lumber trust definitely stripped the city officials of all power and turned affairs over to the sheriff. On this point a quotation from the Industrial Relations Commission Report is particularly illuminating in showing a common industrial condition:

“Free speech in informal and personal intercourse was denied the inhabitants of the coal camps. It was also denied public speakers. Union organizers would not be permitted to address meetings. Periodicals permitted in the camps were censored in the same fashion. The operators were able to use their power of summary discharge to deny free press, free speech, and free assembly, to prevent political activities for the suppression of popular government and the winning of political control. I find that the head of the political machinery is the sheriff.”

In Everett the sheriff’s office was controlled by the Commercial Club and the Commercial Club in turn was dominated, thru an inner circle, by the lumber trust. Acting for the trust a small committee meeting was held on the morning of the 30th with

44

the editor of a trust-controlled newspaper, the secretary of the Commercial Club, two city officials, a banker and a lumber trust magnate in attendance. A larger meeting of those in control met in the afternoon and, pursuant to a call already published in the Everett Herald, several hundred scabs, gunmen, and other open shop advocates were brought together that night at the Commercial Club.

Commissioner of Finance, W. H. Clay, suggested that as Federal Mediator Blackman, an authority on labor questions, was in the city it might be well to confer with him regarding a settlement. Banker Moody said he did not think a conference would be advisable as Mr. Blackman might be inclined to lean toward the side of the laboring men, and at a remark by “Governor” Clough, formerly Governor of Minnesota and spokesman for the mill owners, to the effect that there was nothing to be settled the suggestion was not considered further.

H. D. Cooley, special counsel for a number of the mills, Governor Clough, a prominent mill owner, and others then addressed the meeting in furtherance of the plans already laid. Clough asked McRae if he could handle the situation. McRae said he did not have enough deputies.

“Swear in the members of the Commercial Club, then!” demanded Clough. This was done. Nearly two hundred of the men whose membership had been paid for by the mill owners “volunteered” their services. McRae swore in a few and then, for the first time in his life, found swearing a difficulty, so W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club, who was neither a city nor a county official, administered the remainder of such oaths as were taken by the deputies. The whole meeting was illegal.

From time to time the deputy force was added to until it ran way up in the hundreds. It was divided into sections A, B, C, etc. Each division was assigned to a special duty, one to watch incoming trains for free speech advocates, another to watch the boats for I. W. W. members, and others for various duties such as deporting and beating up workers.

45

This marked the beginning of a reign of terror during which no propertyless worker or union sympathizer was safe from attack.

About this same time the Commercial Club made a pretense of investigating the shingle weavers’ strike. Not one of the strikers was called to give their side of the controversy, and J. G. Brown, international president of the Shingle Weavers’ Union, was refused permission to testify. The committee claimed that the employers could not pay the wages asked. An adverse report was returned and was adopted by the club.

Attorneys E. C. Dailey, Robert Fassett, and George Loutitt, along with a number of other fair minded members who did not favor the open shop program, withdrew from membership on account of these various actions. Their names were placed on the bulletin board and a boycott advised. Feeling against the organization responsible for the chaotic conditions in Everett finally became so strong that practically all of the merchants whose places were not mortgaged or who were not otherwise dependent upon the whims of the lumber barons, posted notices in their windows,

“WE ARE NOT MEMBERS OF THE

COMMERCIAL CLUB.”

Their names, too, were placed on the bulletin board, and the boycott and other devices used in an endeavor to force them into bankruptcy.

Prior to these occurrences and for some time thereafter, the club was addressed by emissaries of the open shop interests. A. L. Veitch, special counsel for the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Association, on one occasion addressed the deputies on labor troubles in San Francisco and the methods used to handle them. Veitch was later one of the attorneys in the case against Thomas H. Tracy, and he was employed by the state, it being stipulated that he receive no state compensation. H. D. Cooley,

46

lumber mill lawyer and former prosecuting attorney, also spoke at different times on the open shop questions. Cooley was likewise an attorney for the prosecution in the Tracy case and he, like Veitch, was retained by “interested parties.” Cooley was one of the anti-union speakers at a meeting of the deputies which was also addressed by F. C. Beach, of San Francisco, president of the M. & M., Robert Moody, president of the First National Bank of Everett, Governor Clough, mill magnate, F. K. Baker, president of the Commercial Club, and Col. Roland H. Hartley, open shop candidate for the nomination as governor of Washington at the pending election. Leigh Irvine, of Seattle, secretary of the Employers’ Association, and Murray, president of the National Association of Manufacturers, were also active in directing the destinies of the Commercial Club.

A special open shop committee was formed, the nature of its operations being apparent when the following two quotations from its minutes, taken from among others of similar purport, are considered:

“Decided to go after advertisements in labor journals and the Northwestern Worker.”[7]

“Matter of how far to go on open shop propaganda at the deputies meeting this morning was discussed. Also the advisability of submitting pledges. Mr. Moody to take up matter of the legality of pledges with Mr. Coleman. Note: At deputies meeting all speakers touched quite strongly on the open shop, and as far as it was possible to see all in attendance seemed favorable.”[8]

Just how far they finally did go is a matter of history. At the time, however, there were appropriations made for the purchase of blackjacks, leaded clubs, guns and ammunition, and for the

47

employment of detectives, labor spies, and “agents provocateur.”[9]

FOOTNOTES:

[2] Sunset Magazine, February 1917. “The I. W. W. and the Golden Rule.”

[3] Supplemental report on “Everett’s Industrial Warfare,” by President Ernest P. Marsh to State Federation of Labor convention held at Everett, Wash., from January 22 to 26, 1917.

[4] Vol. 9, No. 2, The Shingle Weaver, Special Convention Number, February, 1911.

[5] Proposition No. 5, submitted to referendum of membership of Pacific Coast District I. L. A., Riggers and Stevedores Local 38, at their annual election on Jan. 6, 1916.

[6] Dreamland Rink Meeting, Seattle, Nov. 19th, over 5,000 in attendance.

[7] Minutes of Open Shop Committee, Sept. 27th.

[8] Minutes of Open Shop Committee, October 29.

[9] The incidents of the foregoing chapter are corroborated by the sworn testimony of prosecution witnesses Donald McRae, sheriff of Snohomish County; and D. D. Merrill, Mayor of Everett; and by witnesses called by the Defense, W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club: J. G. Brown, International president of the Shingle Weavers’ Union; W. H. Clay, Commissioner of Finance in Everett; Robert Faussett, Everett attorney; Harry Feinberg, one of the defendants; Mrs. Letelsia Fye, Everett citizen; Jake Michel, Secretary Everett Building Trades Council; Herbert Mahler, Secretary Seattle I. W. W. and subsequently secretary of the Everett Prisoners’ Defense Committee; Robert Mills, business agent Everett Shingle Weavers’ Union; James Orr, and Levi Remick, I. W. W. members; James Rowan, I. W. W. organizer; and James P. Thompson, National Organizer for the I. W. W. and a speaker of international reputation.

48

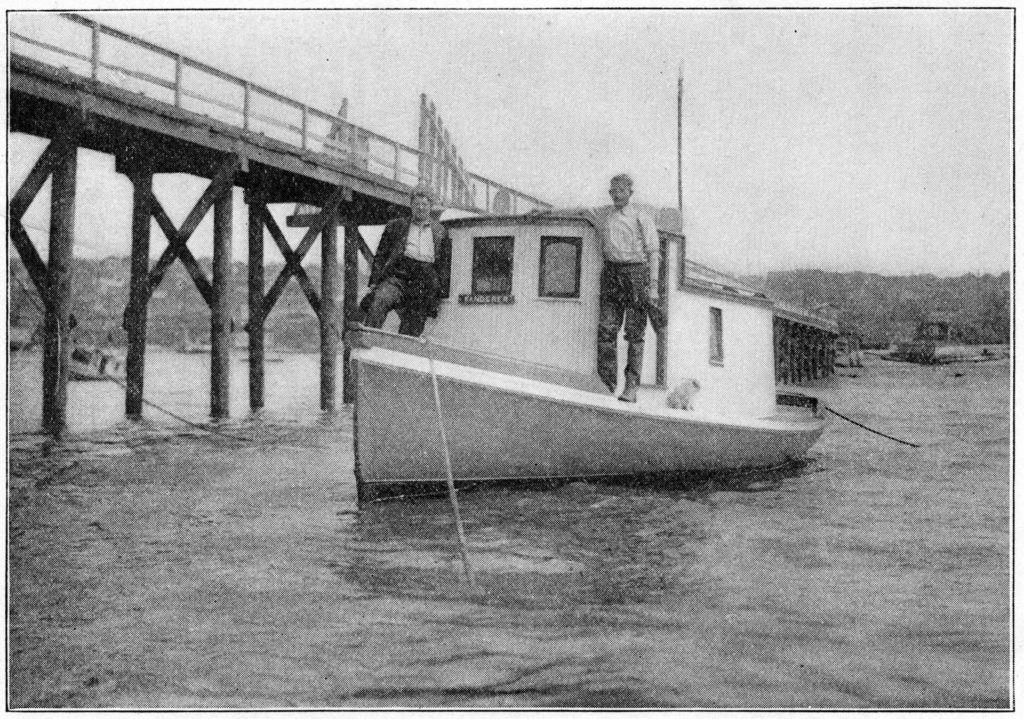

Joe (Red) Doran Capt. Jack Mitten

The Launch Wanderer.