49

CHAPTER III.

A REIGN OF TERROR

No sooner had Mediator Blackman left Everett than the “law and order” forces resumed their hostilities with a bitterness and brutality that seems almost incredible. On September 7th Mrs. Frennette, H. Shebeck, Bob Adams, J. Johnson, J. Fred, and Dan Emmett were dragged from the platform at Hewitt and Wetmore Avenues and were literally thrown into their cells. Next morning Mrs. Frenette was released but the men were “kangarood” for 30 days each. Petty abuses were heaped upon them and Johnson was cast into the “black hole” by the sheriff. Some of the men were severely beaten just before their release a few days afterward.

When Fred Reed and James Dwyer were arrested the next night for street speaking, the crowd of Everett citizens, in company with the few I. W. W. members present, followed the deputies to the county jail, demanding the release of Reed, Dwyer and Peck, and those who had been arrested the night before. In its surging to and from the crowd pushed over a post-rotted picket fence that had been erected in the early days of Everett. This violence, together with cries of “You’ve got the wrong bunch in jail! Let those men out and put the ‘bulls’ in!” was the basis from which the trust-owned press built up a story of a riot and attempted jail delivery. On the same flimsy basis a warrant was issued charging Mrs. Frennette with inciting a riot.

The free speech committee sent John Berg to Everett that same day to retain an attorney for the men held without warrants. He secured the services of E. C. Dailey, and, while waiting to learn the result

50

of the lawyer’s efforts, he went to the I. W. W. hall only to find it closed. A man was there waiting to get his blankets to go to work and Berg volunteered to get them for him. He then went to the county jail and asked for McRae. When McRae came in and learned that Berg wanted to see the secretary in order to get the keys to the hall, he yelled out:

“You are another I. W. W. Throw him in jail, the old son-of-a-b——!”

Without having any charges placed against him, Berg was held until the next morning, when McRae and a deputy took him out in a roadster to a lonely spot on the county road. Forcing him to dismount, McRae ordered Berg to walk to Seattle under threats of death if he returned, and then knocked Berg down and kicked him in the groin as he lay prostrate. McRae was drunk. Berg subsequently developed a severe rupture as a result of this treatment. He managed to make his way to Seattle and in spite of his condition returned to Everett that same night.

Undaunted by their previous deportations, and determined to circumvent the deputies who were seizing men from the railroad trains and regular boats, a body of free speech fighters, on September 9th, took the train to Mukilteo, a village about four miles from Everett, and there, by pre-arrangement, were taken aboard the launch “Wanderer.”

The little boat would not hold the entire party and six men were towed behind in a large dory. There were 17 first class life preservers on board, the captain borrowing some to supplement his equipment.

When the “Wanderer” reached a point about a mile and a half from the Weyerhouser dock a boat was seen approaching. It was the scab tug “Edison,” belonging to the American Tugboat Company. On board was Captain Harry Ramwell, Sheriff McRae and a body of about sixty deputies. When the “Edison” was about 200 feet away the sheriff commenced shooting—but let Captain Jack Mitten tell his own story.

51

“The first shot went over the bow. I don’t know whether there was one or two shots fired, then there was a shot struck right over my head onto the big cast iron muffler. The next shot came on thru the boat,—I had my bunk strapped up against the wall,—and thru the blanket,—and the cotton in the blanket turned the bullet,—and it struck flat on the bottom of the bunk.

“I shut the engine down and went out to the stern door and just as I stepped out there was a shot went right by my head and at the same time McRae hollered out and says ‘You son-of-a-b—, you come over here!’ Says I, “If you want me, you come over here.” With that they brought their boat and my boat up together. Six shots in all were fired.

“McRae commenced to take the people off the boat and when he had them all off he kicked the pilot house open and says, ‘Oho, there is a woman here!’ Mrs. Frennette was sitting in the pilot house. Anyhow, they took her and he says, ‘You’ll get a one piece suit on McNeil’s island for this,’ and then he says to Cap Ramwell—Cap Ramwell was sitting on the side—’This is Oscar Lindstrom, drag him along too.’

“Then they were going to make fast the line—they had made fast my stern line—and as I bent over with the line McRae struck me with his revolver on the back of the head, and when I straightened up he struck me in here, a revolver about that long. (Indicating.) I said something to him and then he ran the revolver right in here in my groin and he ruptured me at the same time. I told him ‘It’s a fine way of using a citizen.’ He says, ‘You’re a hell of a citizen, bringing in a bunch like that,’ he says, ‘to cause a riot in this town.’ I says, ‘Well, they are all union men anyway.’ He says, ‘You shut your damn head or I will knock it clean off!’ and I guess he would, because he had whiskey enough in him at the time to do it.

“There was a small man, I believe they call him Miller, he saw him standing there and he says, ‘You here, too?’ and he hauled off and struck him in the

52

temple and the blood flowed way down over his face and shirt. He struck him again and staggered him. If he hadn’t struck him so he would have gone inboard, he would have gone over the edge, close to the edge.

“Then there was a man by the name of Berg, it seemed he knowed John Berg. He said, ‘You ——, I will fix you so you will never come back!’ and then he went at Berg, but Berg was foxy and kept ducking his head. He rapped him on the shoulders two or three different times, I wouldn’t say how often, but he didn’t draw blood on Berg. (An I. W. W. member named Kurgvel was also beaten on the head and shoulders.)

“They drove us all in alongside of the boiler between the decks, down on the main deck of the “Edison” and kept us there till they docked and got automobiles and the patrol wagon and filed us off into them and took us to jail.”

The arrest of Captain Mitten and acting engineer Oscar Lindstrom made twenty-one prisoners in all, and these were jailed without any charge being placed against them. As Berg was taken into the jail, McRae cursed him roundly, ordering two deputies to hold him while a beating was administered over the shoulders and back with a leather strap loaded with lead on the tip.

The men were treated with great brutality within the jail. One young fellow was asked by the deputies, “Are you an I. W. W.?” and each time the lad answered “Yes!” he was thrown violently against the steel walls of the cell, until his body was a mass of bruises. Mitten was denied a chance to communicate with his Everett friends in order to get bail. The nights were cold and the prisoners had to sleep on the bare floor without blankets.

At the end of nine days all the men were offered their liberty except Mitten. They promptly refused the offer. “All or none!” was their indignant demand, and Peck and Mitten were set at liberty with the rest as a result of this show of solidarity.

53

Upon his release Captain Mitten found that the life preservers had been stolen from his boat, and the flattened bullet removed from his bunk. Scotty Fife, the Port Captain of the American Tugboat Company, told Captain Mitten that he had straightened up the things on the “Wanderer!”

Thus to the crimes of unlawful arrest, false imprisonment, theft, deportation, assault and physical injury, the lumber trust added that of piracy on the high seas. And all this was but a taste of what was yet to come!

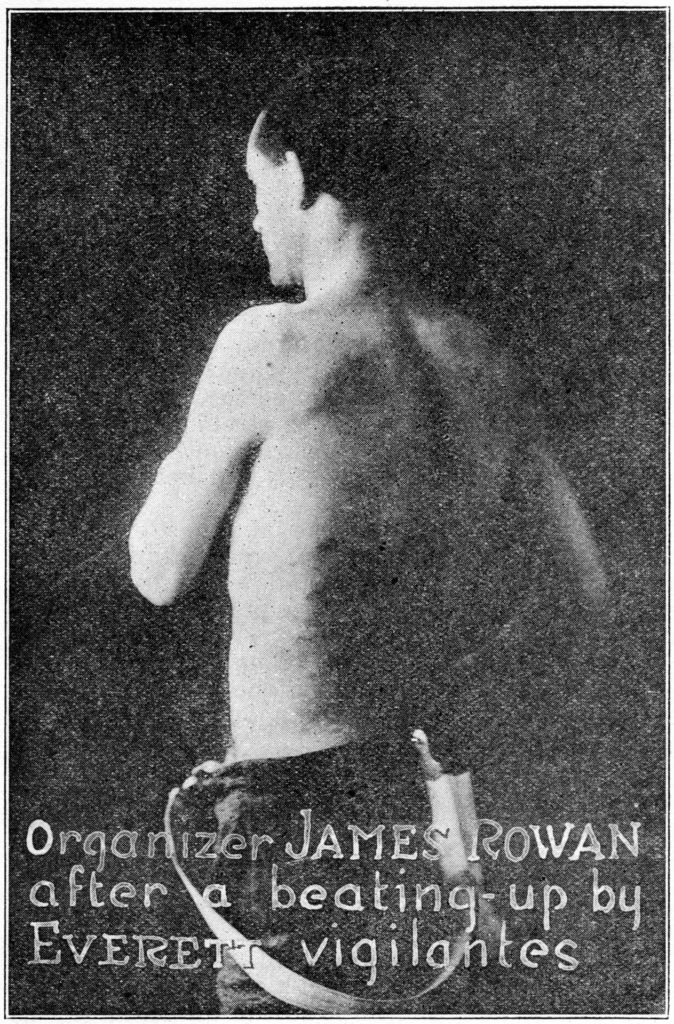

Organizer James Rowan returned to Everett from Anacortes on the afternoon of September 11th and was met at the depot by three deputies who promptly took him to the county jail. There were at that time between thirty and forty other members of the I. W. W. being unlawfully held. Rowan learned that these men had been taken from their cells one at a time and beaten by the deputies, Thorne and Dunn having especially severe cuts on the face and head.

Rowan’s story of the outrage that followed gives a glimpse of the methods employed by the lumber trust.

“As soon as I dropped off the train at Everett I was met by three deputies. One of them told me the sheriff wanted to see me and I asked if he was a deputy. He said, ‘Yes,’ and showed me a badge. Then I went up with two of the deputies to the county jail. In a minute or two Sheriff McRae came in and he was pretty drunk. He caught hold of me and gave me a yank forward, and he says, ‘So you are back, eh?’ and I says ‘Yes.’ And he says ‘We are going to fix you so you won’t come back any more.’ There was some more abusive talk and then I was searched and put in a cell.

“Just after dark that night I was taken out of the cell, my stuff was given back, and McRae says, ‘We are going to start you on the road to Seattle.’ With a deputy he took me out to the automobile and McRae drove the automobile, and we had some conversation. McRae seemed to feel very sore because

54

I told the people on the street that the jail was lousy, and he says ‘We wanted you to get out of here and you would not do it, and now,’ he says, ‘Now instead of dealing with officers you have to deal with a bunch of boob citizens, and there is no telling what these boobs will do.’ There was more talk that is not worth repeating and most of it not fit to repeat anyhow.

“We went out in the country until we came to where the road crosses the interurban tracks about two miles from Silver Lake and McRae told me to get out. He then pointed down the track and says, ‘There is the road to Seattle and you beat it!’ so I started down the track.

“I hadn’t gone far, maybe 50 or 75 yards, when I met a bunch of gunmen. They came at me with guns. They had clubs and they started to beat me up on the head with the butts of their guns and with the clubs. They all had handkerchiefs over their face except one. They threw a cloth over my head and beat me some more on the head with their gun butts and then they dragged me thru the fence at the right-of-way and went a little ways back into the woods. Then they held me down over a log about eighteen inches or two feet in diameter. There were about a dozen of them I would say. Two or three held each arm and two or three each leg and there were four or five of them holding guns around my ribs—they had the guns close around my ribs all the time, several of them—and they tore my clothes off, tore my shirt and coat off. Then one of them beat me on the back, on the bare back with some kind of a sap, I don’t know just what kind it was, but I could hear him grunt every time he was going to strike a blow. I was struck fifty times or more.

“After he got thru beating me they went back to the fence toward the road and I picked up my scattered belongings and went down to Silver Lake, taking the first car to Seattle.”

Rowan exhibited his badly lacerated and bruised back to several prominent Seattle citizens, and then

55

Organizer James Rowan;

Showing his back lacerated by Lumber Trust thugs.

56

had a photograph made, which was widely circulated. Contrary to the expectation of the lumber barons this treatment did not deter free speech fighters from carrying on the struggle. Instead, it brought fresh bodies of free speech enthusiasts to the scene within a short period.

The personnel of the free speech committee changed continually because of the arrest of its members. On Sunday, September 10th, at a mass meeting in Seattle Harry Feinberg and William Roberts were elected to serve. Roberts had just come down from Port Angeles and desired to investigate conditions at first hand, so in company with Feinberg he went to Everett on the 11th. They met Jake Michel, who telephoned to Chief of Police Kelley for permission to hold a street meeting.

“I have no objection to this meeting,” replied Kelley, “but wait a minute, you had better call up McRae and find out.”

Attempts to reach McRae at the Commercial Club and the sheriff’s office met with failure. Meanwhile Feinberg had gone ahead with the meeting, the following being his sworn statement of what transpired:

“I went to Everett at 7:30 Monday night. I got a box and opened a meeting for the I. W. W. There must have been three thousand people on the corner, against buildings and looking out of the windows.

“I spoke about 35 minutes, with the crowd boisterous in their applause. Three companies of deputies and vigilantes, about one hundred and fifty thugs in all, marched down the street and divided up in three companies. One of the deputies came up and told me he wanted me and grabbed me off the box.

“They took me up to the jail, took my description, and my money and valuables, which were not returned. By that time Fellow Worker Roberts was brought in. A drunken deputy came in and grabbed me by the coat and dragged me out of the jail, with the evident permission of the officers. The vigilantes proceeded to beat me up on the jail steps. There

57

were anyway fifty deputies waiting outside and all of them crowded to get a chance to hit me. They gave me a chance to get away finally and shot after me, or in the air, I could not tell which, but I was not hit by the bullets.”

The sworn statement of William Roberts corroborated the foregoing:

“I took the box after Fellow Worker Feinberg had been arrested. The crowd were extreme in their hostility to the lawlessness of the officers. I told them to keep cool, that the I. W. W. would handle the situation, in their own time and way. They arrested me, and, right there, they clubbed me on the head. They brought me to the jail, where Feinberg was at the desk. They took me out of the jail and threw me into the bunch of vigilantes with clubs. They started beating me around the body. One of them said: ‘Do anything, but don’t kill him!’

“Finally one of them hit me on the head and I came out of it and as I was getting away they shot in the air. A bunch of them then jumped into an automobile, came after me and again clubbed me. One of them knocked me out for ten minutes, according to one of the women who were watching.

“While we were in the jail, two men we did not know were brought into the jail with their heads cut open. The vigilantes were clubbing women right and left, and a young girl, about eight years of age, had her head cut open by one of Sheriff McRae’s Commercial Club tools.”

Roberts ran down the street to the interurban depot, where he hid behind a freight car until just before the car left for Seattle. Feinberg, with his face and clothing covered with blood, got on the same car about a mile and a half from Everett and the two returned to Seattle.

John Ovist, a resident of Mukilteo who had joined the I. W. W. in Everett on Labor Day, got on the box and said, “Fellow comrades——” but got no further. He was knocked from the box. Ovist states: “Mr. Henig was standing alongside of me when Sheriff McRae came up and cracked him over

58

the forehead with a club. I don’t know what else happened to him for just then Sheriff McRae came in front of me and pushed the fellow off the box. When the two fellows were arrested I started to speak and McRae took me and turned me over to one of them—I don’t know what you call them—deputies, or whatever they are. He had a white handkerchief around his neck and he took me toward the county jail. There was a policeman standing in front of the jail. If I am not mistaken his name is Ryan, a short heavy-set fellow. I walked by him. Of course, I never thought he was going to hit me, but I felt something over behind. He hit me with a club behind the ear and cut my head until it was bleeding awful.”

“When we came to the county jail, Henig, he was in there already. His face was red and he was full of blood. And they took us into the toilet to have us wash the blood off, and when I came back I heard screams and pounding.

“Then the sheriff recognized me, he had been down in Mukilteo before, and he says, ‘What are you doing up here?’ I said, ‘Well, I didn’t come up here, they brought me up here.’ He says, ‘You are a member of the I. W. W., too.’ So I told him, ‘I don’t see why I should come and ask you what organization I should belong to!’ So he opened the gate and says, ‘Here is a fellow from Mukilteo,’ he says. ‘Beat it!’ And I seen, I guess—a hundred and fifty or maybe two hundred, I didn’t have time to count them, right out back of the jail lined up in lines on either side. And I had to run between them and come out the other end. They banged me on the head with clubs, and all over. I looked bad and I felt worse. I had blue marks on my shoulders and on my hips and under my knees.

“I got thru them and there was a couple ran after me, but I beat it ahead of them. I guess they intended to club me. I ran down to that depot where the electric car goes thru to Seattle and then I turned to look around because the car was at Hewitt and Colby, and as I went down the walk two

59

men stopped me and asked me if I hadn’t had enough. They told me to beat it, and as I turned around the same policeman, Ryan, I think his name is, hit me on the forehead and then pulled his gun and said, ‘Beat it!’ He was drunk and they were all swearing at me.

“After I got a block or so, there were two or three shots. I walked two more blocks and then was so dizzy I had to rest. Finally I walked further and an automobile came past me and I tried to holler but they didn’t hear me. And then I walked a little further and the stage came along and they picked me up.”

Eye witnesses declared that officer Daniels was one of those who fired shots at the fleeing men after they had been forced to run the gauntlet.

Frank Henig, an Everett citizen, tells what happened in these words:

“I will start from the time I left the house. My wife and I, and the little baby were going to the show. When we got on Wetmore there was a big crowd standing there. I had worked the night before in the mill and I had cedar asthma, so I said to my wife, ‘I would like to stay out in the fresh air,’ And she said, ‘All right, I will meet you at nine o’clock at Wetmore and Hewitt.’

“There was quite a crowd and I got up pretty close in front so I could hear the speaker. I stood there a little while and finally the sheriff came along with a bunch of deputies, and the speaker said, ‘Here they come, but now people, I will tell you, don’t start anything, let them start it.’

“They took him off the box and arrested a couple of others with him, and then immediately after that the Commercial Club deputies came along in a row. They had white handkerchiefs around their necks. So I looked out there and the crowd commenced to yell and cheer like, and McRae got excited and started toward me, saying, ‘We have been looking for you before.’ When he said that I stopped—before that I had tried to get farther back—I stopped and he got hold of me. Meanwhile

60

Commissioner Kelley came up and took care of me and McRae walked away a little way. Kelley had hold of my right arm and he pinched me a little bit, and I said ‘Let go Kelley and I will go with you.’

“We stood there a few minutes longer and McRae came back. Kelley said ‘Come along with me,’ and just as I said ‘All right,’ McRae grabbed me by the coat and hit me on the head with a black club fastened to his strap with a leather thong. I was looking right at him and he knocked me unconscious. Then Kelley picked me up and shook me and I came to again, and I fell over the curb of the sidewalk.

“Kelley then turned me over to Daniels, a policeman in Everett, and he turned me over to a couple of Commercial Club deputies. Then Fred Luke came along and said, ‘I will take care of him.’ So we walked a little ways and he said, ‘You better go to the doctor and have that dressed.’ I said to him, ‘Oh, I guess it ain’t so bad,’ and so he said, ‘Come along with me and we will wash up at the jail.’ I said, ‘All right,’ and while I was going up the steps to the jail, why a policeman by the name of Bryan or something like that,—a little short fellow, well anyhow he got canned off the force for being drunk, that is how I heard of him,—when I was kind of slow walking along because I was bleeding pretty bad, he said, ‘Hurry up and get in there, you low-down, dirty son-of-a-b——’ And I answered, ‘I guess I ain’t arrested, I don’t have to hurry in there.’ So he cursed some more.

“I went into the jail and washed up and came back into the office of the county jail. The fellows that they had arrested were sitting in the chairs and McRae came in and grabbed one of the I. W. W.’s—I guess they were I. W. W.’s, anyway one of them that was arrested—and he says, ‘What in hell are you doing up here, don’t you know I told you to keep away from here?’ and while he was going in the door into the back office I saw him haul off with his sap, but I don’t see him hit him, but the little fellow cried like a baby.

61

“McRae came back and he looked at me and said, ‘What in hell are you doing up here?’ I didn’t know what to say for a little while and then I said, ‘I didn’t do nothing, Mac, I don’t see what you wanted to sap me for.’ And he said, ‘I didn’t sap you,’ he said, ‘Kelley hit you.’ Then I said to him, ‘My wife says for me to meet her down at the corner of Wetmore and Hewitt at nine o’clock and I would like to go down there and meet her.’ So he said, ‘All right, you go; you hurry and go.’ I was going out the front door and he said, ‘No, don’t go out there. If you go out there, they will kill you!’ He led me to the back door of the jail, I don’t know where it was, I never was in jail in my life before, and he said, ‘Hurry and beat it, and pull your hat down over your head so they wont know you.’ But when I got to town everybody knew, because there was blood still running all over my face after I washed up.”

Henig endeavored to prosecute McRae for his illegal and unwarranted assault but all attempts to secure a warrant met with failure. Lumber trust law operates only in one direction.

In this raid upon the meeting McRae smashed citizens right and left, women as well as men. He was even seen to kick a small boy who happened to get in his path. Deputy Sam Walker beat up Harry Woods, an Everett music teacher; another deputy was seen smashing an elderly gentleman on the head; still another knocked Mrs. Louise McGuire, who was just recovering from a sprained knee, into the gutter; and Ed Morton, G. W. Carr and many other old-time residents of Everett were struck by the drunken Commercial Club thugs.

Mrs. Leota Carr called up Chief of Police Kelley next morning, the following being an account of the conversation that ensued:

“I said, ‘What are you trying to kill my husband for?’ and he kind of laughed and said he didn’t believe it, and I said, ‘Did you know they struck him over the head last night and he could hardly go to work today?’ He said, ‘My God, they didn’t strike

62

him, did they?’ and I said, ‘They surely did!’ And he said ‘Why there isn’t a better man in town than he is,’ and I said, ‘I know it.’ It surprised me to think that he thought I didn’t know it myself. And then I said, ‘These here deputies are making more I. W. W.’s in town than the I. W. W.’s would in fifty years.’ And he said, ‘I know it.’ Then I said, ‘Why do you allow them to do it? You are the head of the police department.’ He replied, ‘McRae has taken it out of my hands; the sheriff is ahead of me and it is his men who are doing it, and I am not to blame.'”

At the city park four nights after this outrage, only one arrest for street speaking having occurred in the meantime, the aroused citizens of Everett met to hear Attorney E. C. Dailey, T. Webber, and various local speakers deal with the situation, and to view at first hand the wounds of Ovist, Henig and other towns people who had been injured. Thousands attended the meeting, and disapproval of the actions of the Commercial Club and its tools was vehemently expressed.

This remonstrance from the people had some effect. The Commercial Club, knowing that all arrests so far had been unlawful, took steps to “legalize” any further seizing of street speakers at Hewitt and Wetmore Avenues. The lumber interests issued an ordinance preventing street speaking on that corner. The Mayor signed it without ever putting it to a reading, thus invalidating the proposed measure. This made no difference; henceforth it was a law of the city of Everett and as such was due to be enforced by the lumber trust.

During the whole controversy there had not been an arrest made on the charge of violation of any street speaking ordinance. With the new ordinance assumed to be a law, Mrs. Frennette went to Everett and interviewed Chief Kelley. After telling him that the I. W. W. members were being disturbed and mistreated by men who were not in uniform, she said:

63

“It seems that there is an ordinance here against street speaking and we feel that it is unjust. We feel that we have a right to speak here. We are not blocking traffic and we propose to make a test of the ordinance. Will you have one of your men arrest me or any other speaker who chooses to take the box, personally, and bring me to jail and put a charge against me, and protect me from the vigilantes who are beating the men on the street?”

Kelley replied that so far as he was concerned he would do the best he could but McRae had practically taken the authority out of his hands and that he really could not guarantee protection. So a legal test was practically denied.

Quiet again reigned in Everett following the brutalities cited. A few citizens were manhandled for too openly expressing their opinion of mob methods and several wearers of overalls were searched and deported, but the effects of bootleg whiskey seemed to have left the vigilantes.

On Wednesday, Sept. 20th, a committee of 2000 citizens met at the Labor Temple and arranged for a mass meeting to be held in the public park on the following Friday. The meeting brought forth between ten and fifteen thousand citizens, one-third of the total population at least, who listened to speakers representing the I. W. W., Socialists, trades unions and citizens generally. Testimony was given by some of the citizens who had been clubbed by the vigilantes. Recognizing the hostile public opinion, Sheriff McRae promised that the office of the I. W. W. would not again be molested. As he had lied before he was not believed, but, as a test, Earl Osborne went from Seattle to open up the hall once more.

For a period thereafter the energies of the deputies were given to a course of action confined to the outskirts of the city. Migratory workers traveling to and from various jobs were taken from the trains, beaten, robbed and deported. As an example of McRae’s methods and as depicting a phase of the life of the migratory worker the story of “Sergeant” John J. Keenan, sixty-five years old,

64

and still actively at work, is of particular interest:

“I left Great Falls, Mont., about the 5th of September after I had been working on a machine in the harvest about nine miles from town. The boys gathered together—they were coming from North Dakota—and we all came thru together. We had an organization among ourselves. We carried our cards. There was a delegate with us, a field delegate, and I was spokesman, elected by the rank and file of the twenty-two. There was another division from North Dakota on the same train with us, going to Wenatchee to pick apples. We were going to Seattle. I winter in Seattle every year and work on the snow sheds.

“We carried our cooking utensils with us, and when we got off at a station we sent our committee of three and bought our provisions in the store, and two of the cooks cooked the food, and we ate it and took the next train and came on. This happened wherever we stopped.

“We arrived in Snohomish, Wash., on Sept. 23rd at about 8:45 in the morning. When the committee came down I sent out and they brought me back the bills—I was the treasurer as well—one man carried the funds, and they brought back $4.90 worth of food down, including two frying pans, and when I was about cooking, a freight train from Everett pulled in and a little boy, who was maybe about ten years old, he says, ‘Dad, are you an I. W. W.?’ I says, ‘I am, son.’ ‘Well,’ he says, ‘there are a whole bunch of deputies coming out after you.’ I laughed at the boy, I thought he was joshing me.

“About half an hour after the boy told me this the deputies appeared. In the first bunch were forty-two, and then Sheriff McRae came with more, making altogether, what I counted, sixty-four. The first bunch came around the bush alongside the railroad track where I was and the sheriff came in about twenty minutes later with his bunch from the opposite way.

“In the first bunch was a fat, stout fellow with two guns. He had a chief’s badge—a chief of police’s

65

badge—on him. He was facing toward the fire and he says, ‘If you move a step, I will fill you full of lead!’ I laughed at him, says I, ‘What does this outrage mean?’ There was another old gentleman with a chin beard, fat, middling fat, probably my own age, and he picked up my coat which was lying alongside me and looked at my button. He says, ‘Oh, undesirable citizen!’ I says, ‘What do you mean?’ He says, ‘Are you an I. W. W.?’ I says, ‘I am, and I am more than proud of it!’ ‘Well,’ he says, ‘we don’t want you in this county.’ I says, ‘Sure?’ He says, ‘Yes.’ I says, ‘Well, I am not going to stay in this county, I am going to cook breakfast and go to Seattle.’ He says, ‘Do you understand what this means?’ I says, ‘No.’ He says, ‘The sheriff will be here in a few minutes and he will tell you what it means.’ I heard afterward that this man was the mayor of Snohomish.

“I was sitting right opposite the fire with my coffee and bread and meat in my hand when Sheriff McRae came up and says, ‘Who is this bunch?’ So a tall, black deputy, a tall, dark complected fellow, says, ‘They are a bunch of harvest hands coming from North Dakota.’ McRae says, ‘Did you search these men?’ And he says, ‘Yes.’ ‘Did you find any shooting arms on them?’ He says, ‘No.’ They had searched us and we had no guns or clubs.

“McRae then asked, ‘Who is their leader?’ and this old gentleman that spoke to me first, he says, ‘They have no leader, but that old man over there is the spokesman.’ So he came over to me and says, ‘Where are you going?’ I says, ‘I am going to Seattle.’ Then he used an expression that I don’t think is fit for ladies to hear. I says, ‘My mother was a lady and she never raised any of us by the name you have mentioned, and,’ I says, ‘I don’t think I have done anything that I will have to walk out of the county.’ He says, ‘Do you see that track?’ I says, ‘Yes.’ He says, ‘Well, you will walk down that track!’ I says, ‘But for these twenty-one men that are here in my hands I wouldn’t walk a foot for you.’ He says, ‘You get out. I am going to shoot all

66

these things to pieces.’ I says, ‘You will shoot nothing to pieces, I bought them with my hard-earned money.’ He says, ‘All right, take them with you.’ Then he shot up the cans and things, and he says, ‘That is the track to Seattle and you go up it, and if I ever catch you in this county again you will get what you are looking for.’

“So we walked up the hill toward Seattle and there is a town, I think they call it Maltby, and we got there between four and five o’clock in the evening. Fellow Worker Thornton, Adams and Love were the committee men and they asked me how I felt. I told them my feet were pretty sore.

“I went over to the station agent and found out that there was a freight due at 9:30 but that sometimes it didn’t get in until three in the morning. I then asked permission to light a fire and cook some coffee, and after we were thru eating we lay down.

“About 9:30 the train came along and I called the men. As the train was backing up I saw some light come, and one auto throwing her searchlight, and I counted four automobiles. That is all I could count but there were a whole lot of them coming. I says, ‘Men, we have run up against a stone wall.’

“Fellow Worker Love and I—he came off the machine with me in Great Falls—we were first in line and Sheriff McRae and two other men with white handkerchiefs around their necks came forward first and he says, ‘You son-of-a-b——, I thought you were going to Seattle?’ I says, ‘Ain’t I going to Seattle? I can’t go till the train goes,’ I says, ‘you’ve had me walking now till I have no foot under me. What do you mean by this outrage? My father fought for this country and I have a right here. I am on railroad property and have done nothing to anybody.’ McRae then hit Fellow Worker Love on the head and I yelled ‘Break and run, men, or they will kill you!’ He turned around then and he said to me, ‘You dirty old Irish bastard, now I will make you so you can’t run. I’ll show you!’ With that he let drive and hit me, leaving this three cornered mark here (indicating place on head).

67

And when the others went up the track he says, ‘Get now, God damn your old soul, or I will kill you!’ I says, ‘Sheriff, look here, you are a perfect gentleman, you are, to hit a fellow old enough to be your father.’ He made as if to hit me again and then Fellow Worker Love came back and says, ‘Have a heart!’ I says ‘You run,’ and he says ‘No, they are not going to kill you while I am here.’ And Fellow Worker Paterson came back down the track and I says, ‘What is the matter, Paterson, are you crazy? Get the men and tell them to go over the line. Don’t stay in this county or they are liable to murder you!’ Then Love and I went off the track into the thick bushes and lay down till next morning.

“At daylight we got up, went down to the junction and gathered up fifteen of the men. When the train pulled in the trainman asked me where I was going and I said I was going to Seattle. He says, ‘Do you carry a card?’ ‘Yes,’ says I. ‘Produce!’ says he. That is the word the trainmen use. So I put my hand in my pocket and pulled it out. ‘You better get back in the caboose, you are hurt,’ he said. He saw the blood where Fellow Worker Love had bandaged my head with his handkerchief. ‘No,’ says I, ‘Where the men are riding is good enough for me.’ So we went to where the interurban comes in and I was seven men short. I paid two-fifty into Seattle, and we came in, and I made a report to the Seattle locals.”

Incidents similar to this were of almost daily occurrence, scores of deportations taking place during the month of September. Then on the 26th, despite his promises to refrain from molesting the hall, McRae entered the premises, forcibly seized Earl Osborne, the secretary, took him a long distance out in the country, and at the point of a gun made him start the thirty-mile trip on foot to Seattle. On the 29th of September the Everett authorities arrested J. Johnson and George Bradley in Seattle. Johnson was held on an arson charge but no legal warrant for his arrest was issued until October 17th, or until he had been in jail for nineteen

68

days. Then the charge against him was that he had set fire to a box factory—but this was soon changed when it was learned by the authorities that the box factory had not caught fire until after Johnson was in jail, and for the first charge they substituted the claim that Johnson had burned the garage of one Walter Smith, a scab shingle weaver deputy. George Bradley, who had been deported from Everett after having served one day as secretary, was accused of second degree arson as an alleged accomplice. Each man was told that the other had confessed and the best thing to do was to make a clean breast of matters, but this scheme of McRae’s fell thru for two reasons: the men were not guilty, and they had never seen or heard of each other before. Johnson was in jail fifty-eight days without a preliminary hearing. Both men were released on property bonds, and the trials were “indefinitely postponed,” that still being their status at this writing.

No further attempts were made to open the hall after Osborne’s deportation until October 16th when the organization in Seattle again selected a man to act as secretary in Everett. Thomas H. Tracy took charge on that date, remaining in Everett until a few days prior to November 5th, at which time he resigned, his place being taken by Chester Micklin.

During the month of October there were between three and four hundred deportations, the vigilantes operating mainly from the Commercial Club. Many of these “slugging parties” were attended by Mayor D. D. Merrill, Governor Clough, Captain Harry Ramwell, T. W. Anguish, W. R. Booth, Edward Hawse, and other “pillars of society” in Everett. Most of the men were deported without any formalities whatever, and the methods used in handling the others may well be judged by frequent entries on the police blotter to the effect that men arrested by Great Northern detective Fox were ordered turned over to Sheriff McRae by Mayor Merrill. The railroad company, acting in conjunction with the lumber trust, put on a private army, and had its men roughly dressed to resemble honest

69

workingmen. Cases of “hi-jacking” became quite numerous about this time, but no redress from this highway robbery could be had.

On the question of the hiring of armed forces by the railroads the Industrial Relations Commission Report has this to say:

“Under the authority granted by the several states the railroads maintain a force of police, and some, at least, have established large arsenals of arms and ammunition. This armed force, when augmented by recruits from detective agencies and employment agencies, as seems to be the general practice during industrial disputes, constitutes a private army clothed with a degree of authority which should be exercised only by public officials; these armed bodies, usurping the supreme functions of the state and oftentimes encroaching on the rights of citizens, are a distinct menace to public welfare.”

A number of the men deported during September and October were not members of the I. W. W., some even being opposed at the time to the tenet of the organization, “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common,” but almost without exception the non-members who suffered deportation made it a point to join the union when the nearest branch or field delegate was reached. In Everett, delegates working quietly among the millmen, longshoremen, and other workers, were also getting numerous recruits as the class struggle stood forth in its naked form. All the efforts of the lumber trust to suppress the I. W. W. were as tho they had tried to quench a forest fire with gasoline.

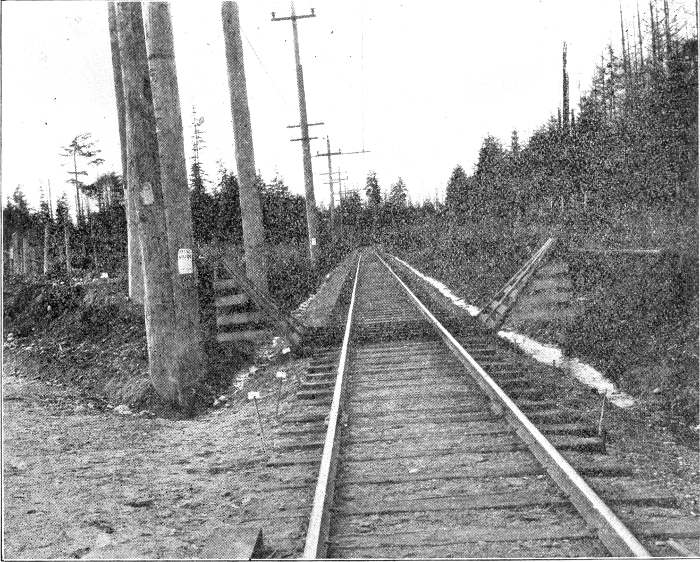

It was on October 30th that forty-one men left Seattle by boat in a determined effort to reach the corner of Hewitt and Wetmore Avenues in order to test the validity of the alleged ordinance prohibiting free speech at that point. They were the first contingent of an army of harvesters who were just returning from a hard season’s labor in the fields

70

Beverly Park

71

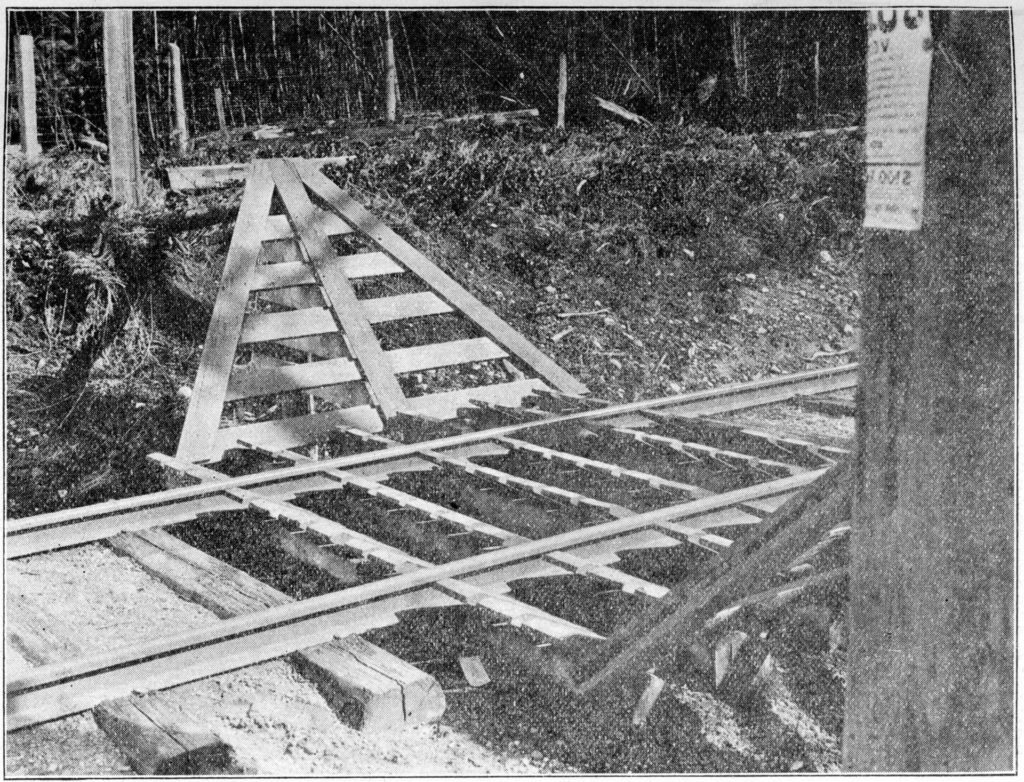

A close up view of Beverly Park showing cattle guards.

72

and orchards. The party was double the size of any free speech group that had tried to enter Everett at any previous time.

They were met at the dock by a drunken band of deputies, most of whom wore white handkerchiefs around their necks as a means of identification. The deputies were armed with guns and clubs, and they outnumbered the I. W. W. body five to one. Several of the lawless crew were so intoxicated they could scarcely stand, and one in particular had to be forcibly restrained by his less drunken associates from attempts to commit murder in the open. The I. W. W. men were clubbed with gun butts and loaded clubs whenever their movements were not swift enough to suit the fancies of the drunken mob. John Downs’ face was an indistinguishable mass of blood where Sheriff McRae had “sapped up” on him and split open his upper lip. Boat passengers who remonstrated were promised the same treatment unless they kept still. In its mad frenzy the posse struck in all directions. So blindly drunk and hysterical was deputy Joseph Irving that he swung his heavy revolver handle with full force onto the head of deputy Joe Schofield. He continued the insane attack, while McRae, awry-eyed and lusting for blood, assisted in the brutal task until warning cried from the other vigilantes showed them their mistake. Schofield was carried to an automobile and hastened to the nearest drug store, where it was found necessary to call a physician to take three stitches to bind together the edges of the most severe wound.

The prisoners were loaded into large auto trucks and passenger cars, more than twenty of which were lined up in waiting, and were taken out to a lonely wooded spot near Beverly Park on the road to Seattle. McRae, with deputies Fred Luke, William Pabst and Fred Plymale, took one I. W. W. out in their five-passenger Reo, McRae afterward endeavored unsuccessfully to prove an alibi because his own car was in a garage. Deputy Sheriff Jefferson Beard also took out a prisoner.

73

Upon their arrival at Beverly the prisoners were made to dismount at the point of guns and stand in the cold drizzling rain until their captors had formed two lines reaching from the roadway to the interurban tracks. There in the darkness the men were forced to run stumbling over the uneven ground down a gauntlet that ended only with the cruel sharp blades of a cattle guard, while on their unprotected heads and shoulders the drunken outlaws rained blow after blow with gun-butts, black-jacks, loaded saps and pick-handles. In the confusion one boy escaped from Ed Hawse, but before he could get away into the brush this bully, weighing about 260 pounds, bore down upon him, and with a couple of other deputies proceeded to beat him well-nigh into insensibility. Deputies who lost their clubs in the scramble aimed kicks at the privates of the men as they passed down the line. Deputy Fred Luke swung at one man with such force that the leather wrist thong parted and the club disappeared into the woods. With drunken deliberation Joseph Irving cracked the head of man after man, informing each one that they were getting an extra dose because of his mistake in beating up a brother deputy. In the thick of it all, smashing, kicking, and screaming obscene curses at the helpless men and boys who dared demand free speech within the territory sacred to the lumber trust, was the deputy-sheriff of Snohomish County, Jefferson E. Beard!

A few of the men broke the lines and ran into the woods, a bullet past their heads warning others from a like attempt. Across the cattle guard, often sprawling on hands and knees from the force of the last blows received, went the men who had cleared the gauntlet. Legs sank between the blades of the guard and strained ligaments and sprained ankles were the result. One man suffered a dislocated shoulder at the hands of a Doctor Allison, another had the bridge of his nose broken by a blow from McRae, and dangerously severe wounds and bruises were sustained by nearly all of the forty-one.

So horrible were the moans and outcries of the

74

stricken men, so bestial were the actions of the infuriated deputies, that one of their own number, W. R. Booth, sickened at the sight and sound, went reeling up the roadway retching as he left the brutal scene.

Attracted by the curses of the deputies, the sound of the blows, and the moans and cries of the wounded men, Mrs. Ruby Ketchum came to the door of her house nearly a quarter of a mile away, and remained there listening to the hideous din, while her husband, Roy Ketchum, and his brother, Lew, went down to the scene of the outrage to investigate. The Ketchum brothers reported that the deputies were formed in two lines ending in six men, three on each side of the cattle guard. A man would be taken out of the car and two deputies would join his arms up behind him meanwhile hammering his unprotected face from both sides as hard as they could strike with their fists. Then the man was started down the line, one deputy following to club him on the back to make him hurry, and the other deputies striking with clubs and other weapons and kicking the prisoner as he progressed. Just before reaching the cattle guard he was made to run, and, in crossing the blades, the three men on the east side of the track would swing their clubs upon his back while the men on the west clubbed him across the face and stomach. This was repeated with the men as fast as they were dragged from the autos. They also heard the sound of blows and then cries of “Oh my God! Doc, don’t hit me again, doc, you’re killing me!” Lew Ketchum took deputy Fred Luke by the coat tails and pulled him back from the cattle guard, asking, “What are you doing, what is going on here?” and Luke replied, “We are beating up forty-one I. W. W.’s.”

Harry Hubbard tells the story in these words from the time the autos arrived at Beverly:

“I got out of the car with another fellow, Rice, and I says, ‘We had better stay together, it looks to me like we were going to get tamped up,’ and somebody grabbed hold of him, and I stood a

75

minute, and then I ran by one fellow up into the woods. Just as I got out of the radius of the automobile lights I fell over a stump on the edge of the embankment. I was in kind of a peculiar predicament and I had to get hold of the stump to pull myself up, and just as I did that some fellow behind me swung with a blackjack and grazed my temple, knocking me to my knees. I got up and he grabbed hold of me and we both fell down the bank together. Then two or three others grabbed me, and this Hawse had me by the collar, and Sheriff McRae walked up and said ‘You are the son-of-a—— that was over here last week,’ and I answered, ‘I was working here last week.’ Then he said, ‘Are you an I. W. W.?’ I said, ‘Yes,’ and he hit me an upward swing on the nose. He repeated, ‘You are an I. W. W., are you?’ and again I said, ‘Yes.’ He then swore at me and said, ‘Say that you ain’t!’ and I replied, ‘No, I won’t say that I ain’t,’ and he hit me three more times on the nose.

“Then the man who was holding my left wrist with one hand and my shoulder with the other, said, ‘Wait a minute until I get a poke at him,’ and McRae said, ‘All right, doc,’ and then someone else said ‘All right Allison, hit him for me!’ This fellow they called Doc Allison hit me and blackened my eye. McRae swore at me, he seemed to be intoxicated and he looked and acted like a maniac, he said ‘If you fellows ever come back some of you will die, that’s all there is to it.’ I said, ‘I don’t think there is any necessity for killing anybody,’ and he answered ‘I will kill you if you come back,’ and he raised his blackjack and said ‘Run!’ I said ‘I wont run,’ and he hit me again and I dropped to the ground. He raised his foot over my face, and used some pretty raw language, and as he stood there with his heel over my face I grabbed hold of a fellow’s leg and pulled myself along so instead of hitting my face his heel scraped my side. Then I got some kicks, three of them in the small of the back around my kidneys.

“When I got up I walked thru the line, there

76

were twenty or thirty different ones hollered for me to run, but I was stubborn and wouldn’t do it. And when I got to the cattle guard and stood at the other side kind of wiping the blood off my face I heard some one coming and I said, ‘Four Hundred,” and he said ‘Yes,’ and he was crying. It was a young boy and I walked down the track with him afterward.

“At the City Hospital in Seattle next day the doctor told me my nose was badly fractured and that I had internal injuries. A few days later my back pained me severely and I passed blood for a time after that.”

C. H. Rice, whose shoulder was dislocated, gives about the same version.

“Two big fellows would hold a man until they were thru beating him and then turn him loose. I was turned loose and ran probably six or eight feet, something like that, and I was hit and knocked down. As I scrambled to my feet and ran a few feet again I was hit on the shoulder with a slingshot. This time I went down and I was dazed, I think I must have been unconscious for a moment because when I came to they were kicking me, and some of them said, ‘He is faking,’ and others said, ‘No, he is knocked out.’ I remember seeing some of the boys during that time running by me, and when they got me up I started to run a bit farther and was knocked down again.

“Then they called for somebody there, addressing him as Dr. Allison, and he grabbed my arm and pulled me up, and he raised my arm up and said, ‘Aw, there is nothing the matter with you,’ and jerked it down again. My arm was out of place, it seemed way over to one side, and I couldn’t straighten it up.

“As I was going over the cattle guard several of them hit me and some one hollered ‘Bring him back here, don’t let him go over there.’ They brought me back and this doctor said ‘You touch your shoulder with your hand,’ and I couldn’t. He says ‘There is nothing the matter with you.’

77

“Then the fellow who was on the dock, and who had been drinking pretty heavily, because they would have to shove him back every once in a while, he shouted out ‘Let’s burn him!’ About that time Sheriff McRae came over and got hold of my throat and said, ‘Now, damn you, I will tell you I can kill you right here and there never would be nothing known about it, and you know it.’ And some one said, ‘Let’s hang him!’ and this other fellow kept hollering ‘Burn him! Burn him!’ McRae kept hitting me, first on one side and then the other, smacking me that way, and then he turned me loose again and hit me with one of those slingshots, and finally he said ‘Oh, let him go,’ and he started me along, following behind and hitting me until I got over the cattleguard.

“I went down to the interurban track until I caught up with some of the boys. They tried to pull my shoulder back into place and then they took handkerchiefs and neckties, and one thing and another, and made a kind of a sling to hold it up. We then went down to the first station and the boys took up a collection and the eight of us who were hurt the worst got on the train and went to Seattle. The others had to walk the twenty-five miles into Seattle. Most of us had to go to the hospital next day.”

Sam Rovinson was beaten with a piece of gaspipe, but taking advantage of the fact that the shooting when Archie Collins made his escape had attracted the attention of the deputies he got thru the gauntlet with only minor injuries. Rovinson testifies that McRae said to him:

“This time we will let you off with this, but next time you come up here we will pop you full of holes.”

“I just came up here to exercise my constitutional right of free speech,” expostulated Rovinson.

“To hell with free speech and the Constitution!” shouted McRae, “You are now in Snohomish county, and we are running the county!”

78

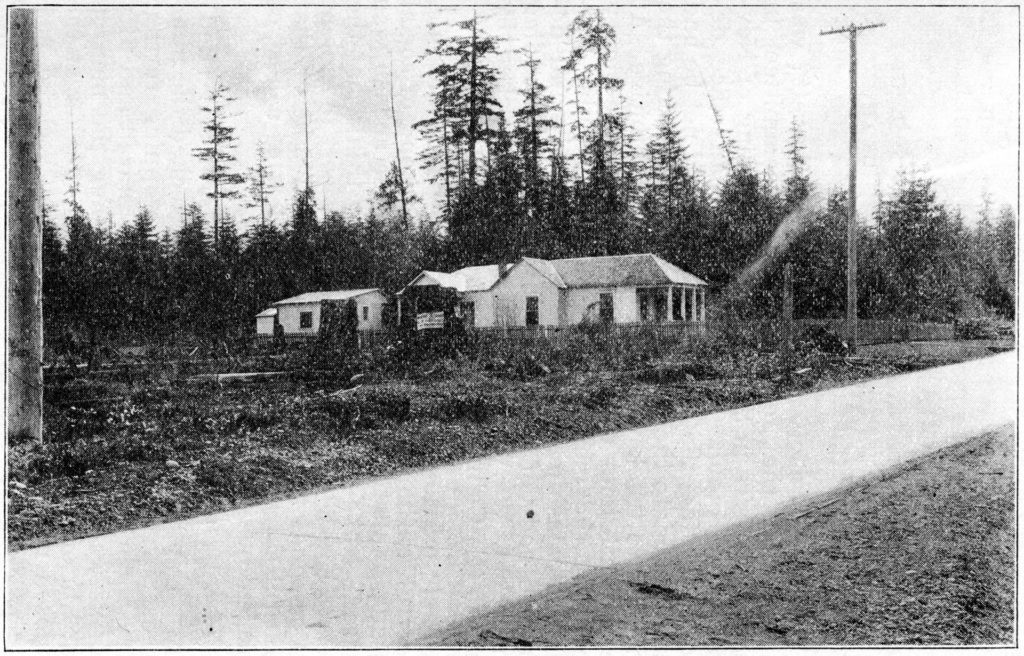

After the deputies had returned to town the two Ketchum brothers took their lanterns and went out to the scene thinking they might find some of the men out there hurt, with a broken leg, or arm or something, and that they could be taken to their house to be cared for. No men were seen, but three covered with blood were found and after examination were returned to where they had been picked up.

Early next morning some of the deputies, frightened at their cowardly actions of the previous night, were seen at Beverly Park making an examination of the ground. Two of them approached the Ketchum residence and asked if any I. W. W.’s had been found lying around there. After being assured that they had stopped short of murder, the deputies departed.

A little later an investigation committee composed of Rev. Oscar McGill of Seattle, and Rev. Elbert E. Flint, Rev. Jos. P. Marlatt, Jake Michel, Robert Mills, Ernest Marsh, E. C. Dailey, Commissioner W. H. Clay, Messrs. Fawcett, Hedge, Ballou, Houghton and others from Everett, made a close examination of the grounds. In spite of the heavy rain and notwithstanding the fact that deputies had preceded them, the committee found blood-soaked hats and hat bands and big brown spots of blood soaked into the cement roadway. In the cattle guard was the sole of a shoe, evidently torn off as one of the fleeing men escaped his assailants.

“Hearing of the occurrence I accompanied several gentlemen, including a prominent minister of the gospel of Everett, next morning to the scene. The tale of that struggle was plainly written. The roadway was stained with blood. The blades of the cattle guard were so stained, and between the blades was a fresh imprint of a shoe where plainly one man in his hurry to escape the shower of blows, missed his footing in the dark and went down between the blades. Early that morning workmen going into the city to work, picked up three hats from the ground, still damp with blood. There can

79

be no excuse for nor extenuation of such an inhuman method of punishment,” reported President E. P. Marsh to the State Federation of Labor.

J. M. Norland stated that “there were big brown blotches on the pavement which we took to be blood. They were perhaps two feet in diameter, and there were a number of smaller blotches for a distance of twenty-five feet. In the vicinity of the cattle guard the soil was disarranged and there were shoe marks near the cattle guard. You could also notice where, in their hurry to get across, they would go in between, and there would be little parts or shreds of clothing there, and on one there was a little hair.”

All that day the talk in Everett centered around the crime of the preceding night. Little groups of citizens gathered here and there to discuss the matter. The deputies went about strenuously denying that they had a hand in the infamous affair, and friends of long standing refused to speak to those who were known positively to have been concerned in the outrage. A number of the ministers of the city conferred regarding a course of action, but finding the problem too deep for them to solve they left it to up to the individual. Various Everett citizens, representing a large degree of public sentiment, felt that the thing to do was to hold an immense mass meeting in order to present the facts of the hideous crime to the whole public. This plan met with immediate approval from many quarters, and the I. W. W. in Seattle was notified of this desire by mail, by telephone, and by means of citizens’ delegations. Rev. Oscar McGill conferred with secretary Herbert Mahler and was quite insistent upon the necessity for such a meeting, as the Everett papers had carried no real information about the affair in Beverly. He brought out the fact that there had been thousands in attendance at the mass meeting in the Everett city park a month or so previous to this occurrence, and the speakers were then escorted by a large body of citizens from the interurban depot to the meeting place, and the feelings of the people

80

were such that similar or even more adequate protection would be given were another meeting held. He suggested that the meeting be held in broad daylight and on a Sunday. That the plan met with the approval of the I. W. W. membership was shown by its adoption at a meeting the night following the trouble at Beverly Park. And the date selected was Sunday, November 5th.

Immediately steps were taken to inform the various I. W. W. branches in the Northwest of the proposed action. Telegrams were sent to Solidarity, and a ringing call for two thousand men to help in the fight for free speech was published in the Industrial Worker. In addition to telegraphing the story and its attendant call for action to the unions of the Pacific Coast there were various members selected from among the forty-one who had been beaten, and these were dispatched to different points to spread the tale of Everett’s atrocities, and to gain new recruits for the “invading army” of free speech fighters.

Seeking the widest possible publicity the free speech committee had printed and circulated thousands of handbills in Everett to call attention to the proposed meeting.

CITIZENS OF EVERETT ATTENTION!

A meeting will be held at the corner of Hewitt and Wetmore Aves., on Sunday, Nov. 5th, 2 p. m. Come and help maintain your and our constitutional right. Committee.

The authorities in Everett were notified, the editors of all the Seattle daily papers were requested to have representatives present at the meeting, and reporters were called in and told of the intentions of the organization. During the week frequent meetings were held in the hall in Seattle to arrange for the incoming free speech fighters, and without an exception all these meetings were held with no

81

examination of membership books and were open to the public. With their cards laid upon the table the members of the Industrial Workers of the World were preparing to call the hand of the semi-legalized outlaws of Snohomish county who had cast aside the law, abrogated the Constitution of the United States, and denied the right of free speech and free assembly.

Following the Beverly affair the Commercial Club redoubled its activities. Blackjacks and “Robinson-clubs,” so called because they were manufactured especially for the deputies by the Robinson Mill, were set aside for revolvers and high power rifles, and the ranks of the deputies were enlarged by the off-scouring and scum of the open shop persuasion.

McRae entered the I. W. W. hall on Friday, Nov. 3rd, the day Thomas H. Tracy turned the office over to Chester Micklin, and abruptly said “By God, I will introduce myself. I am Sheriff McRae! I won’t have a lot of sons-of-bitches hanging around this place like in Seattle.”

Micklin looked at the drunken sheriff a moment and replied, “The constitution guarantees us free speech, free assembly, and free——”

“To hell with the Constitution,” broke in McRae. “We have a constitution here that we will enforce.”

“You believe in unions, you believe in organized labor, don’t you?” asked Micklin.

“Yes, I belonged to the shingle weavers at one time,” returned McRae, “but when the shingle weavers went out on strike I donated $25.00 to their strike fund and they gave me a rotten deal and sent the check back to me, and to hell with the shingle weavers and the rest of the unions!”

Then, as he was leaving the hall, McRae pulled from his pocket a letter; took from it a black cat cut from pasteboard and stuck it in the secretary’s face, saying “That’s the kind of ——s that is in your organization!”

Next morning the sheriff raided the hall and seized the men who were found there, with the

82

exception of the secretary. Turning to Micklin he said boastfully “I’ll bet you a hundred dollars you ——s won’t hold that meeting tomorrow!” McRae was drunk.

The arrested men were searched and deported and, as was the case in every previous arrest and deportation, there was no resistance offered, no physical violence threatened, and no weapons of any character found upon any of the I. W. W. men.

That night the deputies were secretly assembled at the Commercial Club where they were given their final instructions by the lumber trust and ordered to report fully armed and ready for action at the blowing of the mill whistles. With these preparations the open shop forces were ready to go to still greater lengths to uphold “law and order!”

The answer of the I. W. W. to this damnable act of violence at Beverly Park and to the four months of terrorism that had preceded it was a call for two thousand men to enter Everett, there to gain by sheer force of numbers that right of free speech and peaceable assembly supposed to have been guaranteed them by the Constitution of the United States.[10]

FOOTNOTE:

[10] (The incidents in the foregoing chapter are corroborated by the sworn testimony of I. W. W. men who were shot at, beaten, robbed, and abused; by citizens of Everett and Seattle who were also beaten and mistreated or who witnessed the scenes; by physicians, attorneys, public officials, members of craft unions, and by deputies who hoped to make amends by testifying to the truth for the defense.)

83

The Ketchum Home near Beverly Park