177

CHAPTER VII.

THE DEFENSE

The case for the defense opened on Monday morning of April 2nd when Vanderveer, directly facing the judge and witness chair from the position vacated by the prosecution counsel, moved for a directed verdict of not guilty on the ground that there had been an absolute failure of evidence upon the question of conspiracy, any conspiracy of which murder was either directly or indirectly an incident, and there was no evidence whatever to charge the defendant directly as a principal in causing the death of Jefferson Beard. The motion was denied and an exception taken to the ruling of the court.

Fred Moore made the opening statement for the defense. In his speech he briefly outlined the situation that had existed in Everett up to and including November 5th and explained to the jury the forces lined up against each other in Everett’s industrial warfare. Not for an instant did the attention of the jury flag during the recital.

Herbert Mahler, secretary of the I. W. W. in Seattle during the series of outrages in Everett, was the first witness placed upon the stand. Mahler told of the lumber workers’ convention and the sending of organizer James Rowan to make a survey of the industrial situation in the lumber centers, Everett being the first point because of its proximity to Seattle and not by reason of any strikes that may have existed there. The methods of conducting the free speech fight, the avoidance of secrecy, the ardent desire for publicity of the methods of the lumber trust as well as the tactics of the I. W. W., were clearly explained.

Cooley cross-examined Mahler regarding the

178

song book with reference to the advocacy and use of sabotage, asking the witness:

“How about throwing a pitchfork into a threshing machine? Would that be all right?”

“There are circumstances when it would be, I suppose,” replied Mahler. “If there was a farmer deputy who had been at Beverly Park, I think they certainly would have a right to destroy his threshing machine.”

“You think that would justify it?” inquired Cooley.

“Yes,” said the witness, “I think that if the man had abused his power as an officer and the person he abused had no other way of getting even with him and that justice was denied him in the courts, I fully believe that he would be. That would not hurt anybody; it would only hurt his pocketbook.”

“Now what is this Joe Hill Memorial Edition?”

“Joe Hillstrom, known as Joe Hill, had written a number of songs in the I. W. W. Song Book and he was murdered in Utah and the song book was gotten out in memory of him,” responded Mahler.

“He was executed after having been convicted of murder in the first degree, and sentenced to death. And you say he was murdered?” said Cooley.

“Yes,” said Mahler with emphasis. “Our contention has been that Hillstrom did not have a fair trial and we are quite capable of proving it. I may say that President Wilson interceded in his behalf and was promptly turned down by Governor Spry of Utah. Hillstrom was offered a commutation of sentence and he refused to take it. He wanted a retrial or an acquittal. When the President of the United States had interceded with the Governor of Utah, when various labor organizations asked that he be given a retrial, and a man’s life is to be taken from him, and people all over the country ask for a retrial, that certainly should be granted to him.”

James P. Thompson was placed upon the stand to explain the principles of the I. W. W. The courtroom was turned into a propaganda meeting during

179

the examination of the witness. One of the first features was the reading and explanation of state’s exhibit “K,” the famous I. W. W. preamble which has been referred to on various occasions as the most brutally scientific exposition of the class struggle ever penned:

I. W. W. PREAMBLE

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system.

We find that the centering of the management of industries into fewer and fewer hands makes the trade unions unable to cope with the ever growing power of the employing class. The trade unions foster a state of affairs which allow one set of workers to be pitted against another set of workers in the same industry, thereby helping defeat one another in wage wars. Moreover, the trade unions aid the employing class to mislead the workers into the belief that the working class have interests in common with their employers.

These conditions can be changed and the interests of the working class upheld only by an organization formed in such a way that all its members in any one industry, or in all industries, if necessary, cease work whenever a strike or lockout is on in any department thereof, thus making an injury to one an injury to all.

Instead of the conservative motto, “A fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work,” we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, “Abolition of the wage system.”

It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism. The army of production

180

must be organized, not only for the every day struggle with capitalists, but also to carry on production when capitalism shall have been overthrown. By organizing industrially we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.

“Men in society represent economic categories,” said Thompson. “By that I mean that in the world of shoes there are shoemakers, and in the world of boats there are seamen, and in this society there are economic categories called the employing class and the working class. Now, between them as employing class and working class there is nothing in common. Their interests are diametrically opposed as such. It is not the same thing as saying that human beings have nothing in common. The working class and the employing class have antagonistic interests, and the more one gets the less remains for the other.

“Labor produces all wealth,” continued Thompson, “and the more the workers have to give up to anyone else the less remains for themselves. The more they get in wages the less remains for the others in the form of profits. As long as labor produces for the other class all the good things of life there will be no peace; we want the products of labor ourselves and let the other class go to work also.

“The trades unions are unable to cope with the power of the employers because when one craft strikes the others remain at work and by so doing help the company to fill orders, and that is helping to break the strike. If a group of workers strike and win, other workers are encouraged to do likewise: if they strike and lose, other workers are discouraged and employers are encouraged to do some whipping on their own account.

“We believe in an industrial democracy; that the industry shall be owned by the people and operated on a co-operative plan instead of the wage plan; that there is no such thing as a fair day’s pay; that we should have the full product of our labor in the co-operative system as distinguished from the wage system.

181

“Furthermore,” went on the witness, as the jury leaned forward to catch his every word, “our ideas were suggested to us by conditions in modern industry, and it is the historical mission of the workers to organize, not only for the preliminary struggles, but to carry on production afterward.”

“We object to this!” shouted Mr. Cooley, and the court sustained the objection.

Despite continual protests from the prosecution Thompson gave the ideas of the I. W. W. on many questions. Speaking of free speech the witness said:

“Free speech is vital. It is a point that has been threshed out and settled before we were born. If we do not have free speech, the children of the race will die in the dark.”

The message of industrial unionism delivered thru the sworn testimony of a labor organizer was indeed an amazing spectacle. Judge Ronald never relaxed his attention during the entire examination, the jury was spell-bound, and it was only by an obvious effort that the spectators kept from applauding the various telling points.

“There is overwork on one hand,” said Thompson, “and out-of-work on the other. The length of the working day should be determined by the amount of work and the number of workers. You have no more right to do eight or ten or twelve hours of labor when others are out of work, despondent, committing suicide, than you have to drink all the water, if that were possible, while others are dying of thirst.

“Solidarity is the I. W. W. way to get their demands. We do not advocate that the workers should organize in a military way and use guns and dynamite. The most effective weapon of labor is economic power: the modern wage workers are the living parts of industry and if they fold their arms, they immediately precipitate a crisis, they paralyze the world. No other class has that power. The other class can fold their arms, and they do most of the time, but our class has the economic power. The

182

I. W. W. preaches and teaches all the time that a far more effective weapon than brickbats or dynamite is solidarity.

“We have developed from individual production, to social production, yet we still have private ownership of the means of production. One class owns the industries and doesn’t operate them, another class operates the industries and does not own them. We are going to have a revolution. No one is more mistaken than those who believe that this system is the final state of society. As the industrial revolution takes place, as the labor process takes on the co-operative form, as the tool of production becomes social, the idea of social ownership is suggested, and so the idea that things that are used collectively should be owned collectively, presents itself with irresistible force to the people of the twentieth century. So there is a struggle for industrial democracy. We are the modern abolitionists fighting against wage slavery as the other abolitionists fought against chattel slavery. The solution for our modern problems is this, that the industries should be owned by the people, operated by the people for the people, and the little busy bees who make the honey of the world should eat that honey, and there should be no drones at all in the hives of industry.

“When we have industrial democracy you will know that the mills, the mines, the factories, the earth itself, will be the collective property of the people, and if a little baby should be born that baby would be as much an owner of the earth as any other of the children of men. Then the war, the commercial struggles, the clashes between groups of conflicting interests, will be a night-mare of the past. In the place of capitalism with its one class working and its other class enjoying, in the place of the wages system with its strife and strikes, lockouts and grinding poverty, we will have a co-operative system where the interests of one will be to promote the interests of all—that will be Industrial Democracy.”

183

Thompson explained the meaning of the sarcastic song, “Christians at War,” to the evident amusement of the jury and spectators. The witness was then asked about Herve’s work on anti-patriotism in this question by attorney Moore:

“What is the attitude of your organization relative to internationalism and national patriotism?”

“We object to that as incompetent and immaterial,” cried Veitch of the prosecution.

“What did you put this book in for then?” said Judge Ronald in a testy manner as he motioned the witness to proceed with his answer.

“In the broader sense,” answered Thompson, “there is no such thing as a foreigner. We are all native born members of this planet, and for the members of it to be divided into groups or units and to be taught that each nation is better than the other leads to clashes and the world war. We ought to have in the place of national patriotism—the idea that one people is better than another,—a broader conception, that of international solidarity. The idea that we are better than others is contrary to the Declaration of Independence which declares that all men are born free and equal. The I. W. W. believes that in order to do away with wars we should remove the cause of wars; we should establish industrial democracy and the co-operative system instead of commercialism and capitalism and the struggles that come from them. We are trying to make America a better land, a land without child slaves, a land without poverty, and so also with the world, a world without a master and without a slave.”

When the lengthy direct examination of Thompson had been finished, the prosecution questioned him but five minutes and united in a sigh of relief as he left the stand.

The next witness called was Ernest Nordstrom, companion of Oscar Carlson who was severely wounded on the Verona. Nordstrom testified rather out of his logical order in the trial by reason of the

184

fact that he was about to leave on a lengthy fishing trip to Alaska. His testimony was that he purchased a regular ticket at the same time as his friend Carlson, but these tickets were not taken up by the purser. The original ticket of this passenger was then offered in evidence. The witness stated that the first shot came from almost the same place on the dock as did the words “You can’t land here.” He fell to the deck and saw Carlson fall also. Carlson tried to rise once, but a bullet hit him and he dropped; there were nine bullet holes in him. Nordstrom was asked:

“Did you have a gun?”

“No sir.”

“Did Carlson have a gun?”

“No sir.”

“Did you see anybody with a gun on the boat?”

“No. I didn’t.”

Organizer James Rowan then gave his experiences in Everett, ending with a vivid recital of the terrible beating he had received at the hands of deputies near Silver Lake. Upon telling of the photograph that was taken of his lacerated back he was asked by Veitch:

“What was the reason you had that picture taken?”

“Well,” said Rowan, in his inimitable manner, “I thought it would be a good thing to get that taken to show up the kind of civilization that they had in Everett.”

Dr. E. J. Brown, a Seattle dentist, and Thomas Horner, Seattle attorney, corroborated Rowan’s testimony as to the condition of his back. They had seen the wounds and bruises shortly after the beating had been administered and were of the opinion that a false light was reflected on the photograph in such a way that the severest marks did not appear as bad as they really were.

Otto Nelson, Everett shingle weaver, gave testimony regarding the shingle weavers’ strikes of 1915 and 1916 but was stopped from going into detail by the rulings of the court. He told also of the

185

peaceful character of all the I. W. W. meetings in Everett, and stated that on one occasion police officer Daniels had fired two shots down one of the city streets at an I. W. W. man who had been made to run the gauntlet.

H. P. Whartenby, owner of a five-ten-fifteen cent store in Everett, said that the I. W. W. meetings were orderly, and further testified that he had been ordered out of the Commercial Club on the evening of November 5th but not until he had seen that the club was a regular arsenal, with guns stacked all over the place.

To establish the fact that the sidewalks were kept clear, that there was no advocacy of violence, that no resistance was offered to arrest, and that the I. W. W. meetings were well conducted in every particular, the defense put on in fairly rapid succession a number of Everett citizens: Mrs. Ina M. Salter, Mrs. Elizabeth Maloney, Mrs. Letelsia Fye, Bruce J. Hatch, Mrs. Dollie Gustaffson, Miss Avis Mathison, Mrs. Peter Aiken, Mrs. Annie Pomeroy, Mrs. Rebecca Wade, F. G. Crosby, and Mrs. Hannah Crosby. The fact that these citizens, and a number of other women who were mentioned in the testimony, attended the I. W. W. meetings quite regularly, impressed the jury favorably. Some of these women witnesses had been roughly handled by the deputies. Mrs. Pomeroy stated that the deputies, armed with clubs and distinguished by white handkerchiefs around their necks, invaded one meeting and struck right and left. “And they punched me at that!” said the indignant witness.

“Punched you where?” inquired Vanderveer in order to locate the injury.

“They punched me on the sidewalk!” answered the witness, and the solemn bailiff had to rap for order in the court room.

Cooley caught a Tartar in his cross-examination of Mrs. Crosby. He inquired:

“Did you hear the I. W. W.’s say that when they got a majority of the workers into this big union

186

they would take possession of the industries and run them themselves?”

“Why certainly!”

“You did hear them say they would take possession?”

“Why certainly!” flashed back the witness. “That’s the way the North did with the slaves, isn’t it? They took possession without ever asking them. My people came from the South and they had slaves taken away from them and never got anything for it, and quite right, too!”

“Then you do believe it would be all right, yourself?” said Cooley.

“I believe that confiscation would be perfectly right in the case of taking things that are publicly used for the public good of the people——.”

“That’s all,” hastily cut in Cooley.

“That they should be used then by the people and for the people!” finished the witness.

“That’s all!” cried Cooley loudly and more anxiously.

Frank Henig, the next witness, told of having been blackjacked by Sheriff McRae and exhibited the large scar on his forehead that plainly showed where the brutal blow had landed. He stated that he had tried to secure the arrest of McRae for the entirely unwarranted attack but was denied a warrant.

Jake Michel, secretary of the Everett Building Trades Council, gave evidence regarding a number of the I. W. W. street meetings. He was questioned at length about what he had inferred from the speeches of Rowan, Thompson and others. Replying to one question he said:

“I think the American Federation of Labor uses the most direct action that any organization could use.”

“In a strike?”

“Yes.”

“And by that you mean a peaceful strike?” said Cooley suggestively.

187

“Well, I haven’t seen them carry on very many peaceful ones yet,” replied Michel.

Cooley asked Michel whether Rowan had said that “the workers should form one great industrial union and declare the final and universal strike; that is, that they should remain within the industrial institutions and lock the employers out for good as owners?”

“I never heard him mention anything about locking anyone out; I think he wanted to lock them in and make them do some of the work!” answered Michel.

“You haven’t any particular interest in this case, have you?” asked Cooley with a sneer.

“Yes, I have!” replied Michel with emphasis.

When asked what this particular interest was, Michel caused consternation among the ranks of the prosecution by replying:

“The reason I have that interest is this; I have two sons and two daughters. I want to see the best form of organization so that the boys can go out and make a decent living; I don’t want my girls to become prostitutes upon the streets and my boys vagabonds upon the highways!”

Harry Feinberg, one of the free speech prisoners named on the first information with Watson and Tracy, was then placed on the stand and questioned as to the beating he had received at the hands of deputies, as to the condition of Frank Henig after McRae’s attack, and upon matters connected with various street meetings at which he had been the speaker. Mention of the name of George Reese brought forth an argument from the prosecution that it had not been shown that Reese was a detective. After an acrimonious discussion Vanderveer suddenly declared:

“Just to settle this thing and settle it for now and all the time, I will ask a subpoena forthwith for Philip K. Ahern and show who Reese is working for.”

The subpoena was issued and a recess taken to

188

allow it to be served. As Vanderveer stepped into the hall, detective Malcolm McLaren said to him, “You can’t subpoenae the head of the Pinkerton Detective Agency!”

“I have subpoenaed him,” responded Vanderveer shortly as he hurried to the witness room.

While awaiting the arrival of this witness, Feinberg was questioned further, and was then taken from the stand to allow the examination of two Everett witnesses, Mrs. L. H. Johnson and P. S. Johnson, the latter witness being withdrawn when Ahern put in an appearance.

Vanderveer was very brief, but to the point, in the examination of the local head of the Pinkerton Agency.

“Mr. Ahern, on the fifth day of November you had in your employ a man named George Reese?”

“Yes sir.”

“For whom was he working, thru you, at that time?”

“For Snohomish County.”

“That’s all!” said Vanderveer triumphantly.

Cooley did not seem inclined to cross-examine the witness at any length and Vanderveer in another straightforward question brought out the fact that Reese was a Pinkerton employe during the Longshoremen’s strike—this being the time that Reese also was seated as a delegate to the Seattle Trades Council of the A. F. of L.

189

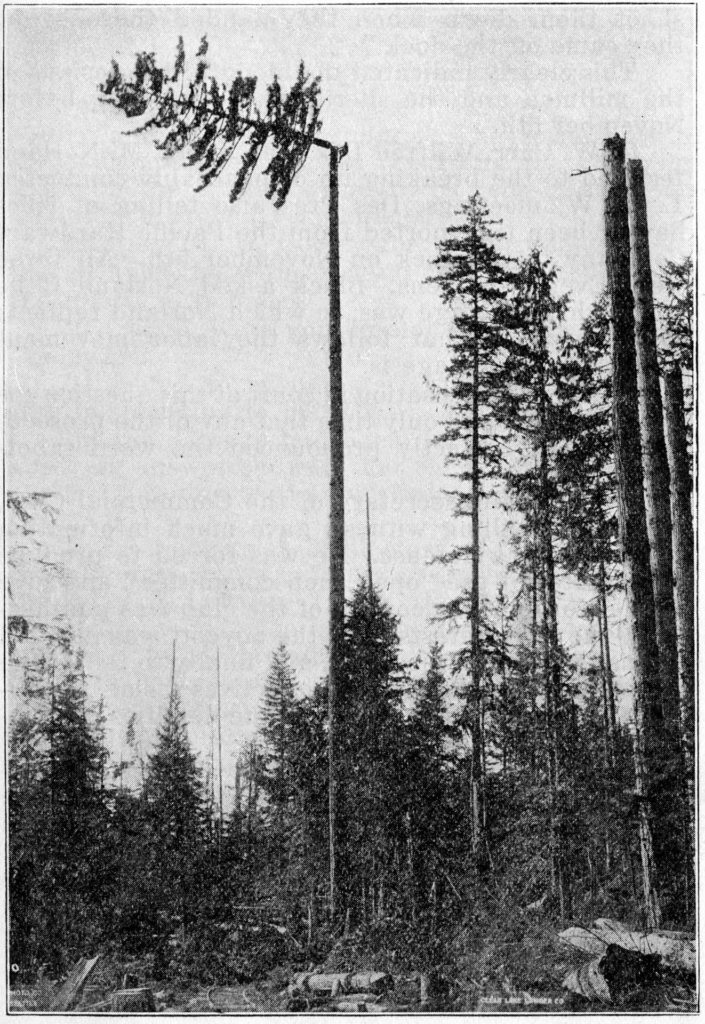

Cutting off top of tree to fit block for flying machine.

A portion of the testimony of Mrs. L. H. Johnson was nearly as important as that concerning Reese. She recited a conversation with Sheriff McRae as follows:

“McRae said he would stop the I. W. W. from coming to Everett if he had to call out the soldiers. And I told him the soldiers wouldn’t come out on an occasion like this, they were nothing but Industrial Workers of the World and they had a right to speak and get people to join their union if they wanted to. And he said he had the backing of the millmen to keep them out of the city, and he was

190

going to do it if he had to call the soldiers out and shoot them down when they landed there, when they came off the dock.”

This clearly indicated the bloodthirsty designs of the millmen and the sheriff at a time long before November 5th.

G. W. Carr, Wilfred Des Pres, and J. M. Norland testified to the breaking up of peaceably conducted I. W. W. meetings, Des Pres also telling of rifles having been transported from the Pacific Hardware Company to the dock on November 5th. All three were Everett citizens. Black asked Norland if he knew what sabotage was, to which Norland replied:

“Everybody that follows the labor movement knows what sabotage is.”

There was a sensation in court at this question for it was the first and only time that any of the prosecution counsel correctly pronounced the word sabotage!

W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club, altho an unwilling witness, gave much information of value to the defense. He was forced to produce the minutes of the “open shop committee” and give up the story of how control of the club was purchased by the big interests, how the boycott was invoked against certain publications, and finally to tell of the employment of Pinkerton detectives prior to November 5th, and to give a list of the deputies furnished by the Commercial Club.

During the examination of this witness some telegrams, in connection with the testimony, were handed up to the judge. While reading these Judge Ronald was interrupted by a foolish remark from Black to Vanderveer. Looking over his glasses the judge said:

“Every time I start to read anything, you gentlemen get into a quarrel among yourselves. I am inclined to think that the ‘cats,’ some of them, are here in the courtroom.”

“I will plead guilty for Mr. Black, Your Honor!” said Vanderveer quickly, laughing at the reference to sabotage.

191

Testimony to further establish the peaceable character of the I. W. W. meetings and the rowdyism of the police and deputies was given by witnesses from Everett: Gustaf Pilz, Mrs. Leota Carr, J. E. McNair, Ed Morton, Michael Maloney, Verne C. Henry and Morial Thornburg. The statements of these disinterested parties regarding the clubbings given to the speakers and to citizens of their acquaintance proved very effective.

Attorney H. D. Cooley for the prosecution was placed upon the witness stand and Vanderveer shot the question at him:

“By whom were you employed in this case, Mr. Cooley?”

“Objected to as immaterial!” cried Veitch, instantly springing to his feet.

But the damage had been done! The refusal to allow an answer showed that there were interested parties the prosecution wished to hide from the public.

Levi Remick related the story of the deportation from Everett, and was followed on the witness stand by Edward Lavelly, James Dwyer, and Thomas Smye, who testified to different atrocities committed in Everett by McRae and the citizen deputies. Their evidence had mainly to do with the acts of piracy committed against the launch “Wanderer” and the subsequent abuse of the arrested men. A little later in the trial this testimony was fully corroborated by the statements of Captain Jack Mitten. During Mitten’s examination by Black the old Captain continually referred to the fact that the life preservers and other equipment of his boat had been stolen while he was in jail. The discomfiture of the youthful prosecutor was quite evident.

J. H. Buel impeached the testimony of state’s witness Judge Bell who had made the claim that a filer at the Clark-Nickerson mill had been assaulted by a member of the I. W. W. Vanderveer asked this witness:

“What was the name of the man assaulted?”

192

“Jimmy Cain.”

“Who did it?”

“I did.”

“Are you an I. W. W.?”

“No sir.”

“Were you ever?”

“No sir.”

Louis Skaroff followed with a detailed story of the murderous attack made upon him by Mayor Merrill in the Everett jail, his story being unshaken when he was recalled and put thru a grilling cross-examination.

William Roberts, who had been beaten and deported with Harry Feinberg, related his experience. The childish questions of Black in regard to the idea of abolishing the wages system nettled this witness and caused him to exclaim, “the trouble is that you don’t understand the labor movement.”

James Orr then told of having his money stolen by the officials so they might pay the fares of twenty-two deported men, and John Ovist followed with the tale of the slugging he had received upon the same occasion that Feinberg, Roberts and Henig were assaulted.

Attorneys George W. Loutitt and Robert Faussett, of Everett, stated that the reputation of McRae for sobriety was very bad. Both of these lawyers had resigned from the Commercial Club upon its adoption of an open shop policy.

Thomas O’Niel testified regarding street meetings and other matters in connection with the case. Cooley asked the witness how many people usually attended the meetings.

“It started in with rather small meetings,” said the witness, “and then every time, as fast as they were molested by the police, the crowd kept growing until at last the meetings were between two and three thousand people.”

The witness said he had read considerable about industrial unionism, and tho he was shocked at first he had come to believe in it.

193

“Until now you are satisfied that their doctrines taken as a whole are proper and should be promulgated and adopted by the working class?” inquired Cooley.

“In this way,” answered O’Niel, “it was not the I. W. W. literature that convinced me so much as the actions of the side that was fighting them.”

“That is, you believe they were right because of the actions of the people on the other side?” said Cooley.

“Yes,” responded the witness, “because I think there are only two people interested in this movement, the people carrying on the propaganda and the people fighting the propaganda, and I saw the people who were fighting the propaganda use direct action, sabotage, and every power, political and industrial, they used it all to whip this organization, and then I asked myself why are they fighting this organization. And the more deeply I became interested, the more clearly I saw why they were doing it, and that made me a believer in the I. W. W.”

Mrs. Louise McGuire followed this witness with testimony about injuries she had received thru the rough treatment accorded her by citizen deputies engaged in breaking up a street meeting.

W. H. Clay, Everett’s Commissioner of Finance, was brought on the stand to testify that he was present and active at the conference that resulted in the formation of the citizen deputies.

John Berg then related his experiences at the time he was taken to the outskirts of Everett and deported after McRae had kicked him in the groin until a serious injury resulted. Owing to the fact that the jury was a mixed one Berg was not permitted to exhibit the rupture. This witness also told his experience on the “Wanderer” and his treatment in the jail upon his arrest.

Oscar Lindstrom then took the stand and corroborated the stories of the witnesses who had testified about the shooting up of the “Wanderer” and the beating and jailing of its passengers. H. Sokol,

194

better known as “Happy,” also told of his experience on the “Wanderer” and gave the facts of the deportation that had taken place on August 23rd.

Irving W. Ziegaus, secretary to Governor Lister, testified that the letter concerning Everett sent from the Seattle I. W. W. had been received; Steven M. Fowler identified certain telegrams sent from Everett to Seattle officials by David Clough on November 5th; after which Chester Micklin, who had been jailed in Everett following the tragedy, corroborated parts of the story of Louis Skaroff.

The evidence of state’s witness, Clyde Gibbons, was shattered at this stage of the trial by the placing of Mrs. Lawrence MacArthur on the stand. This witness, the proprietor of the Merchants Hotel in Everett, produced the hotel register for November 4th and showed that Mrs. Frennette had registered at that time and was in the city when Gibbons claimed she was holding a conversation in an apartment house on Yesler Way in Seattle.

The defense found it necessary to call witnesses who logically should have been brought forward by the prosecution on their side of the case. Among these was the famous “Governor” Clough, citizen deputy and open shop mill owner. David Clough unwillingly testified to having been present at the deportation of twenty-two I. W. W. members on August 23rd, having gone down to the dock at 8:30 that morning, and also to his interest in Joseph Schofield, the deputy who had been injured by his brother outlaws on the dock just before the Beverly Park deportations.

Mahler and Micklin were recalled for some few additional questions, and were followed on the stand by Herman Storm, who gave testimony about the brutal treatment received by himself and his fellow passengers on the launch “Wanderer.” John Hainey and Joseph Reaume also gave details of this outrage.

“Sergeant” J. J. Keenan, who had become a familiar figure because of his “police” duty in the

195

outer court corridor from the inception of the trial, then took the witness stand and recounted his experiences at Snohomish and Maltby, his every word carrying conviction that the sheriff and his deputies had acted with the utmost brutality in spite of the advanced age of their victim. John Patterson and Tom Thornton corroborated Keenan’s testimony.

A surprise was sprung upon the prosecution at this juncture by the introduction on the witness stand of George Kannow, a man who had been a deputy sheriff in Everett and who had been present when many of the brutalities were going on. He told of the treatment of Berg after the “Wanderer” arrests.

“He was struck and beaten and thrown down and knocked heavily against the steel sides of the tank, his head striking on a large projecting lock. He was kicked by McRae and he hollered ‘My God, you are killing me,’ and McRae said he didn’t give a damn whether he died or not, and kicked him again and then shoved him into the tank.”

The gauntlet at the county jail was described in detail and the spirit of the free speech fighters was shown by this testimony:

“Yes, I heard some of them groan. They all took their medicine well, tho. They didn’t holler out but some of them would groan; some of them would go down pretty near to their knees and then get up, then they would get sapped again as they got up. But they never made any real outcries.”

The witness stated that “Governor” Clough was a regular attendant at the deportation parties and so also were W. R. Booth, Ed Hawes, T. W. Anguish, Bill Pabst, Ed Seivers, and Will Taft. He described McRae’s drunken condition and told of drunken midnight revels held in the county jail. His testimony was unshaken on cross-examination.

Mrs. Fern Grant, owner of the Western Hotel and Grant’s Cafe, testified that Mrs. Frennette was in her place of business in Everett on the morning of the tragedy, thus adding to the evidence that Clyde Gibbons had perjured himself in testifying for the prosecution.

196

A party of Christian Scientists, who had attended a lecture in Everett by Bliss Knapp, told of the frightful condition of the eight men who had taken the interurban train to Seattle following their experience at Beverly Park. Mrs. Lou Vee Siegfried, Christian Science practitioner, Thorwald Siegfried, prominent Seattle lawyer, Mrs. Anna Tenelli and Miss Dorothy Jordan were corroborated in their testimony by Ira Bellows, conductor on the interurban car that took the wounded men to Seattle.

Another break in the regular order of the trial was made at this point by the placing on the stand of Nicholas Conaieff, member of the I. W. W., who was to leave on the following day with a party of Russians returning to their birthplace to take part in the revolution then in progress. Conaieff stated that the first shot came from the dock. His realistic story of the conditions on the Verona moved many in the courtroom to tears. In his description Conaieff said:

“I was wounded myself. But before I was wounded and as we were lying there three or four deep I saw a wounded man at my feet in a pool of blood. Then I saw a man with his face up, and he was badly wounded, probably he was dead. There were three or four wounded men alongside of me. The conditions were so terrible that it was hard to control one’s self, and a young boy who was in one pile could not control himself any longer; he was about twenty years old and had on a brown, short, heavy coat, and he looked terrified and jumped up and went overboard into the water and I didn’t see him any more.”

Mrs. Edith Frennette testified to her movements on the day of the tragedy and denied the alleged threats to Sheriff McRae. Lengthy cross-examination failed to shake her story.

Members of the I. W. W. who had been injured at Beverly Park then testified. They were Edward Schwartz, Harry Hubbard, Archie Collins, C. H. Rice, John Downs, one of the defendants, Sam Rovinson and Henry Krieg. Any doubt as to the truth

197

of their story was dispelled by the testimony of Mrs. Ruby Ketchum, her husband Roy Ketchum, and her brother-in-law Lew Ketchum, all three of whom heard the screams of the victims and witnessed part of the slugging near their home at Beverly Park. Some members of the investigation committee who viewed the scene on the morning after the outrage gave their evidence as to the finding of bits of clothing, soles of shoes, bloodstained hats and loose hat-bands, and blotches of blood on the paved roadway and cattle guard. These witnesses were three ministers of the gospel of different denominations, Elbert E. Flint, Joseph P. Marlatt, and Oscar H. McGill. The last named witness also told of having interviewed Herbert Mahler, secretary of the I. W. W. in Seattle, following a conference with Everett citizens, with the object of having a large public demonstration in Everett to expose the Beverly Park affair and to prevent its repetition. It was after this interview that the call went out for the I. W. W. to hold a public meeting in Everett on Sunday, November 5th. Mahler was recalled to the stand to verify McGill’s statement in the matter of the interview.

This testimony brought the case up to the events of November 5th and the defense, having proven each illegal action of the sheriff, deputies and mill owners, and disproven the accusations against the I. W. W., proceeded to open to the gaze of the public and force to the attention of the jury the actual facts concerning the massacre on the Verona.

An important witness was Charles Miller, who viewed the tragedy from a point about four hundred feet from the Verona while on the deck of his fishing boat, the “Scout.” He stated that the Verona tilted as soon as the first shots came. Miller placed the model of the boat at the same relative position it had occupied as the firing started on Bloody Sunday and the prosecution could not tangle up this witness on this important point. The “identification” witnesses of the prosecution were of necessity liars

198

if the stern of the Verona was at the angle set by Miller.

C. M. Steele, owner of apartment houses and stores in Everett, stated that he had been in a group who saw an automobile load of guns transported to the dock prior to the docking of the Verona, this auto being closely followed by a string of other machines. The witness tried to get upon the dock but was prevented by deputies who had a rope stretched clear across the entrance near the office of the American Tug Boat Company. He saw the boat tilt as the firing started and noticed that the stern swung out at the time. This testimony was demonstrated with the model. Harry Young, chauffeur, corroborated this testimony and told of rifle fire from the dock.

Mrs. Mabel Thomas, from a position on Johnson’s float quite near the Verona, told of the boat listing until the lower deck was under water, almost immediately after the firing started. Mrs. Thomas testified that “one man who was facing toward the Improvement Dock, raised his hands and fell overboard from the hurricane deck as tho he were dead. His overcoat held him to the top of the water for a moment and then he went down. One jumped from the stern and then there were six or seven in the water. One got up thru the canvas and crawled back in. One man that fell in held up his hands for a moment and sank. There were bullets hitting all around him.”

Mr. Carroll Thomas, husband of the preceding witness, gave the same testimony about the men in the water and stated that he saw armed men on the Improvement Dock.

The testimony of Ayrold D. Skinner, a barber in Everett at the time of the tragedy and who had been brought from California to testify, was bitterly attacked by Veitch but to no avail. When the Verona landed Skinner was so situated as to command a view of the whole proceedings. He told of the boat listing, the men falling in the water and being shot, and his testimony about a man on board the tug

199

“Edison” firing a rifle directly across the open space on the dock in the direction of the Verona was unshakeable. This witness also testified that about ten deputies with rifles were running back and forth in a frightened manner and were firing from behind the Klatawa slip. The witness saw Dick Hembridge, superintendent of the Canyon Lumber Company, Carl Tyre, timekeeper, Percy Ames, the boom man, and a Dr. Hedges. The last two came up to where the witness was, each bearing a rifle. Skinner stated that he said to Ames, “Percy, what is the world coming to?” and Ames broke down as tho he felt something were wrong. Then Dr. Hedges came running up from where the boat was, he was white in the face, and he cried “Don’t go down there, boys; they are shooting wild, you don’t know where in hell the shots are coming from.”

Carl Ryan, night watchman of the Everett Shingle Company, N. C. Roberts, an Everett potter, Robert Thompson and Edward Thompson testified about the angle of the boat, as to rifles on the dock, the shooting from the tug “Edison” and from the Improvement Dock, in support of witnesses who had previously testified.

Alfred Freeman, I. W. W. member who was on the Verona, testified about the movements of those who made the trip to Everett and told of the conditions on the boat. His testimony, and that of numerous other I. W. W. witnesses, disproved the charges of conspiracy.

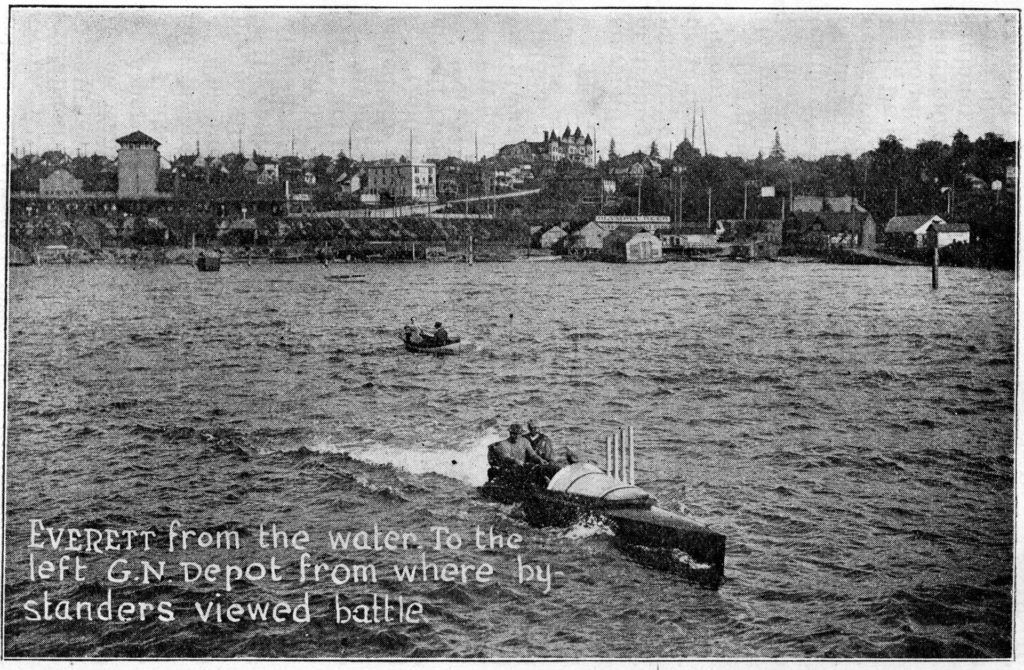

I. W. McDonald, barber, John Josephson, lumber piler, and T. M. Johnson, hod carrier, all of Everett, stated that the shots from the boat did not come until after there had been considerable firing from the dock. These witnesses were among the thousands of citizens who overlooked the scene from the hillside by the Great Northern depot.

200

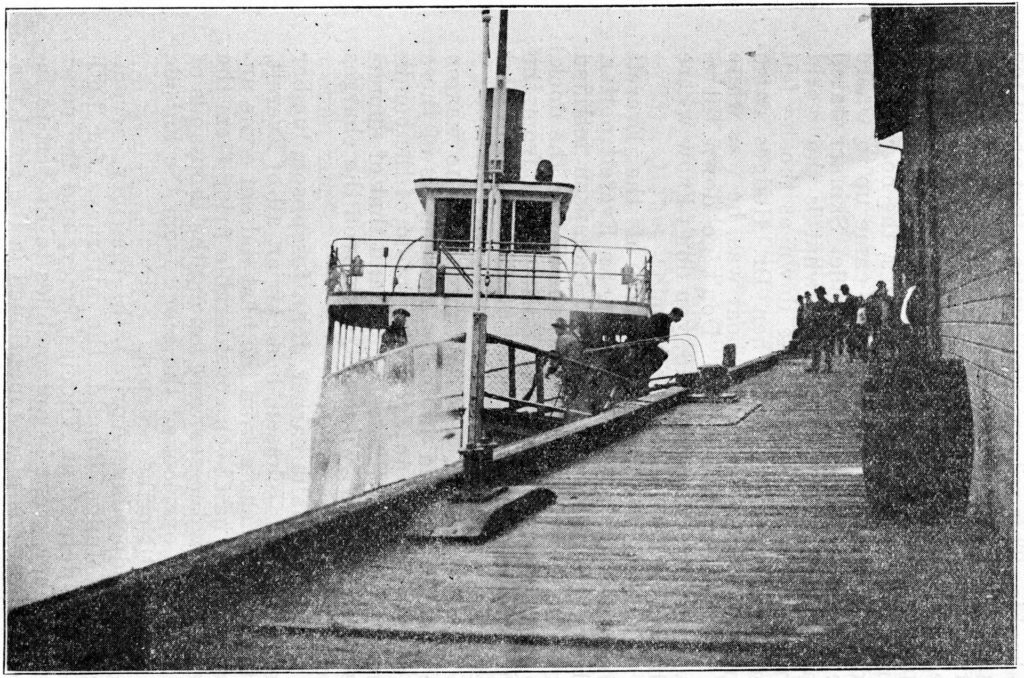

VERONA AT EVERETT DOCK,

under same tide condition as at time of Massacre.

On Wednesday, April 18th, the jury, accompanied by Judge Ronald, the attorneys for both sides, the defendant, Thomas Tracy, and the court stenographer, went in automobiles to Everett to inspect the various places mentioned in the court

201

proceedings. The party stopped on the way to Everett to look over the scene of the Beverly Park outrages of October 30th. No one spoke to the jury but Judge Ronald, who pointed out the various features at the request of the attorneys in the background.

After visiting the corner of Hewitt and Wetmore Avenues, the party went to the city dock. Both warehouses were carefully examined, the bulletholes, tho badly whittled, being still in evidence. Bulletholes in the floor, clock-case, and in the walls still showed quite plainly that the firing from within the warehouse and waiting room had been wild. Bullets imbedded in the Klatawa slip on the side toward the Bay also gave evidence of blind firing on the part of the deputies. In the floor of the dock, between the ship and the open space near the waiting room, were several grooves made by bullets fired from the shore end of the dock. These marks indicated that the bullets had taken a course directly in line with the deputies who were in the front ranks as the Verona landed.

The party boarded the Verona and subjected the boat to a searching examination, discovering that the stairways, sides, and furnishings were riddled with shot holes. The pilot house, in particular, was found to have marks of revolver and high power rifle bullets, in addition to being closely marked with small shot holes, some of the buck-shot still being visible.

The captain swung the boat out to the same angle as it had been on November 5th, this being done at a time when it was computed that the tide would be relatively the same as on the date of the tragedy. Someone assumed the precise position at the cabin window that Tracy was alleged to have been in while firing. The jury members then took up the positions which the “identification witnesses” had marked on a diagram during their testimony. The man in the window was absolutely invisible!

A photograph was then taken from the point where “Honest” John Hogan claimed to have been when he saw Tracy firing and another view made by

202

a second camera to show that the first photograph had been taken from the correct position. These were later introduced as evidence.

No testimony was taken in Everett but on the re-opening of court in Seattle next morning Frank A. Brown, life insurance solicitor, testified that McRae dropped his hand just before the first shot was fired from somewhere to the right of the sheriff. He also identified a Mr. Thompson, engineer of the Clark-Nickerson mill, and a Mr. Scott, as being armed with guns having stocks. Mike Luney, shingle weaver, told of a fear-crazed deputy running from the dock with a bullethole in his ear and crying out that one of the deputies had shot him. Fred Bissinger, a boy of 17, told of the deputies breaking for cover as soon as they had fired a volley at the men on the boat. It was only after the heavy firing that he saw a man on the boat pull a revolver from his pocket and commence to shoot. He saw but two revolvers in action on the Verona.

One of the most dramatic and clinching blows for the defense was struck when there was introduced as a witness Fred Luke, who was a regular deputy sheriff and McRae’s right-hand man. Luke’s evidence of the various brutalities, given in a cold, matter-of-fact manner, was most convincing. He stated that the deputies wore white handkerchiefs around their necks so they would not be hammering each other. He contradicted McRae’s testimony about Beverly Park by stating positively that the sheriff had gone out in a five passenger car, and not in a roadster as was claimed, and that they had both remained there during the entire affair. He told how he had swung at the I. W. W. men with such force that his club had broken from its leather wrist thong and disappeared into the woods. When questioned about the use of clubs in dispersing street crowds at the I. W. W. meetings he said:

“I used my sap as a club and struck them and drove them away with it.”

“Why didn’t you use your hands and push them out?” asked Cooley.

203

“I didn’t think we had a right to use our hands,” said the big ex-deputy.

“What do you mean by that?” said the surprised lawyer.

“Well,” replied the witness, “what did they give us the saps for?”

Cooley also asked this witness why he had struck the men at Beverly Park.

“Well,” replied the ex-deputy, “if you want to know, that was the idea of the Commercial Club. That was what they recommended.”

Luke, who was a guard at the approach to the dock on November 5th, told of having explained the workings of a rifle to a deputy while the shooting was in progress. The state at first had contended that there were no rifles on the dock and later had made the half-hearted plea that none of the rifles which were proven to have been there were fired.

Following this important witness the defense introduced Fird Winkley, A. E. Amiott, Dr. Guy N. Ford, Charles Leo, Ed Armstrong, mate of the Verona and a witness for the state, and B. R. Watson, to corroborate the already convincing evidence that the stern of the Verona was swung quite a distance from the dock.

Robert Mills, business agent of the Everett Shingle Weavers, who had been called to the stand on several occasions to testify to minor matters, was then recalled. He testified that it was his hand which protruded from the Verona cabin window in the photographs, and that his head was resting against the window jamb on the left hand side as far out as it would be possible to get without crawling out of the window. As Mills was a familiar figure to the entire jury and was also possessed of a peculiarly unforgettable type of countenance, the state’s identification of Tracy was shown to have been false.

The Chief of Police of Seattle, Charles Beckingham, corroborated previous testimony by stating that the identification and selection of I. W. W. men had been made from a dark cell by two Pinkerton

204

men, Smith and Reese, aided by one of the defendants, I. P. McDowell, alias Charles Adams.

Malcolm McLaren was then placed upon the stand and the admission secured that he was a detective and had formerly been connected with the Burns Agency. Objection was made to a question about the employment of McLaren in the case, to which Vanderveer replied that it was the purpose of the defense to prove that the case was not being prosecuted by the State of Washington at all. In the absence of the jury Vanderveer then offered to prove that McLaren had been brought from Los Angeles and retained in the employ of certain mill owners, among them being “Governor” Clough and Mr. Moody of the First National Bank, and that McLaren had charge of the work of procuring the evidence introduced by the state. He offered to prove that Veitch and Cooley were employed by the same people. The court sustained the objection of the state to the three offers.

Testimony on various phases of the case was then given by Mrs. Fannie Jordan, proprietor of an apartment house in Seattle, Nick Shugar, Henry Luce, Paul Blakenship, Charles W. Dean, and later on by Oliver Burnett.

Captain Chauncey Wiman was called to the stand, but it happened that he had gone into hiding so soon after the boat landed that he could testify to nothing of particular importance. From his appearance on the witness stand it seemed that he was still nearly scared to death.

Another surprise for the prosecution was then sprung by placing Joseph Schofield on the witness stand. Schofield told of having been beaten up at the city dock by Joseph Irving, during the time they were lining up the forty-one I. W. W. men for deportation. The witness displayed the scar on his head that had resulted from the wound made by the gun butt, and described the drunken condition of McRae and other deputies on the occasion of his injury. And then he told that “Governor” Clough had gone to his wife just a couple of days before he

205

took the witness stand and had given her $75.00. This deputy witness was on the dock November 5th, and he described the affair. He swore that McRae had his gun drawn before any shooting started, that there were rifles in use on the dock, that a man was firing a Winchester rifle from the tug Edison. He was handed a bolt action army rifle to use but made no use of it. Schofield voluntarily came from Oregon to testify for the defense.

Chief Beckingham resumed the stand and was asked further about McDowell, alias Adams. He said:

“We sent a man in with this man Adams, who was in constant fear that somebody might see him, and he would stand way back that he might tip this man with him and this man’s fingers came out to identify the I. W. W. men who were supposed to have guns.”

“What inducements were made to this man Adams?” asked Vanderveer.

“In the presence of Mr. Cooley and Mr. Webb and Captain Tennant and myself he was told that he could help the state and there would be no punishment given him. He was taken to Everett with the impression that he would be let out and taken care of.”

Another ex-deputy, Fred Plymale, confirmed the statements of Fred Luke in regard to McRae’s use of a five passenger car at Beverly Park and showed that it was impossible for the sheriff to have attended a dance at the hour he had claimed. The efforts of the prosecution to shake the testimony that had been given by Fred Luke was shown by this witness who testified that he had been approached by Mr. Clifford Newton, as agent for Mr. Cooley, and that at an arranged conversation McRae had tried to have him state that the runabout had been used to go to the slugging party.

Walter Mulholland, an 18 year old boy, and Henry Krieg, both of whom were members of the I. W. W. and passengers on the Verona, then testified in detail about the shattering gun fire and the

206

wounding of men on board the boat. Mulholland told of wounds received, one bullet still being in his person at that time. Krieg, not being familiar with military terms, stated that there were many shells on the deck of the Verona after the trouble, and the prosecution thought they had scored quite a point until re-direct examination brought out the fact that Henry meant the lead bullets that had been fired from the dock.

E. Carl Pearson, Snohomish County Treasurer, rather unwillingly corroborated the testimony of ex-deputies Luke and Plymale in regard to the actions of McRae at Beverly Park.

The witness chair seemed almost to swallow the next nine witnesses who were boys averaging about twelve years in age. These lads had picked up shells on and beneath the dock to keep as mementos of the “Battle.” Handfuls of shells of various sizes and description, from revolver, rifle and shotgun, intermingled with rifle clips and unfired copper-jacketed rifle cartridges, were piled upon the clerk’s desk as exhibits by these youthful witnesses. After the various shells had been classified by L. B. Knowlton, an expert in charge of ammunition sales for the Whiton Hardware Company of Seattle for six years, the boys were recalled to the stand to testify to the splintered condition of the warehouses, their evidence proving that a large number of shots had been fired from the interior of the warehouses directly thru the walls. The boys who testified were Jack Warren, Palmer Strand, Rollie Jackson, William Layton, Eugene Meives, Guy Warner, Tom Wolf, Harvey Peterson, and Roy Jensen. Veitch, by this time thoroly disgusted with the turn taken by the case, excused these witnesses without even a pretense of cross-examination.

Completely clinching this link in the evidence against the citizen deputies was the testimony of Miss Lillian Goldthorpe and her mother, Hannah Goldthorpe. Miss Goldthorpe, waitress in the Commercial Club dining room, picked up some rifle shells that had fallen from the rifles stacked in the

207

office, and also from the pocket of one of the hunting coats lying on the floor. She took these home to her mother who afterward turned them over to Attorney Moore. She also identified certain murderous looking blackjacks as being the same as those stored in the Club. It is hardly necessary to state that the open-shop advocates who continually prate about the “right of a person to work when and where they please” were not slow about taking away Lillian’s right to work at the Commercial Club after she had given this truthful testimony!

James Hadley, I. W. W. member on the Verona, told how he had dived overboard to escape the murderous fire and had been the only man in the water to regain a place on the boat.

“I saw two go overboard and I didn’t see them any more,” said Hadley. “Then I saw another man four feet from me and he seemed to be swimming all right, and all of a sudden he went down and I never saw him any more. I was looking right at him and he just closed his eyes and sank.”

Mario Marino, an 18 year old member of the I. W. W., then told of the serious wounds he had received on the boat. He was followed by Brockman B. Armstrong, another member of the union, who was close to the rail on the port side of the boat. He saw a puff of smoke slightly to the rear of McRae directly after the sound of the first shot. A rifle bullet cut a piece out of his forehead and a second went thru his cap and creased his scalp, felling him to his knees. Owen Genty was shot thru the kidney on the one side of him, and Gust Turnquist was hit in the knee on the other. As he lay in the heap of wounded men a buckshot buried itself in the side of his head near the temple. As the Verona was pulling out he tried to crawl to shelter and was just missed by a rifle bullet from the dock situated to the south.

Archie Collins, who had previously testified about Beverly Park, was then called to the stand to tell of the trip to Everett and the trouble that resulted. Prosecutor Black displayed his usual asininity by

208

asking in regard to preparations made by Verona passengers:

“What were they taking or not taking?”

“There might be two or three million things they were not taking,” cut in Judge Ronald chidingly.

Black’s examination of the various witnesses was aptly described by Publicity Agent Charles Ashleigh in the Industrial Worker, as follows:

“His examinations usually act as a soporific; heads are observed nodding dully thruout the courtroom and one is led to wonder whether, if he were allowed to continue, there would not be a sort of fairy-tale scene in which the surprised visitor to the court would see audience, jury, lawyers, judge, prisoner and functionaries buried in deep slumber accompanied only by a species of hypnotic twittering which could be traced eventually to a dignified youth who was lulled to sleep by his own narcotic burblings but continued, mechanically, to utter the same question over and over again.”

During this dreamy questioning Black asked about the men who were cleaning up the boat on its return trip, with a view to having the witness state that there were empty shells all over the deck. His question was:

“Did you pick anything up from the floor?”

Instantly the courtroom was galvanized into life by Collin’s startling answer:

“I picked up an eye, a man’s eye.”

The witness had lifted from the blood-stained deck a long splinter of wood on which was impaled a human eye!

The story of Fred Savery was typical of the unrecognized empire builders who make up the migratory class. Fred was born in Russia, his folks moving to Austria and then migrating to Canada when the lad was but two years old. At the age of nine he started at farm work and at twelve he was big enough to handle logs and work in the woods. Savery took the stand in his uniform of slavery, red mackinaw shirt, stagged-off pants, caulked shoes, and a battered slouch hat in his hand. The honest

209

simplicity of his halting French-Canadian speech carried more weight than the too smooth flowing tales told by the well drilled citizen deputies on whom the prosecution depended for conviction.

Cooley dwelt at great length on the constant travel of this witness, a feature incidental to the life of every migratory worker. Even the judge tired of these tactics and told the prosecution that there was no way to stop them from asking the interminable questions but it was merely a waste of time. But all of Cooley’s dilatory tactics could not erase from the minds of the listeners the simple, earnest, sincere story Fred Savery told of the death of his fellow worker, Hugo Gerlot.

Charles Ashleigh was then placed upon the witness stand to testify to having been selected as one of the speakers to go to Everett on November 5th. He stated that he had gone over on the Interurban and had returned that afternoon at four o’clock. After the prosecution had interrogated him about certain articles published subsequent to the tragedy Ashleigh was excused.

To impeach the testimony of William Kenneth, wharfinger at the City Dock, the defense then introduced Peter Aikken of Everett. Following this witness Owen Genty, one of the I. W. W. men wounded on the Verona, gave an account of the affair and stated that the first shot came from a point just to the rear of the sheriff.

Raymond Lee, a youth of 19 years, told of having gone to Everett on the day of the Beverly Park affair in order to mail free speech pamphlets directly to a number of Everett citizens. He went to the dock at the time of the deportation, getting past the deputies on a plea of wanting to see his uncle, his youth and neat appearance not being at all in accord with the current idea of what an I. W. W. member looked like. Lee was cross-questioned at great length by Veitch. This witness told the story of the death of Abraham Rabinowitz on the Verona in these few, simple words:

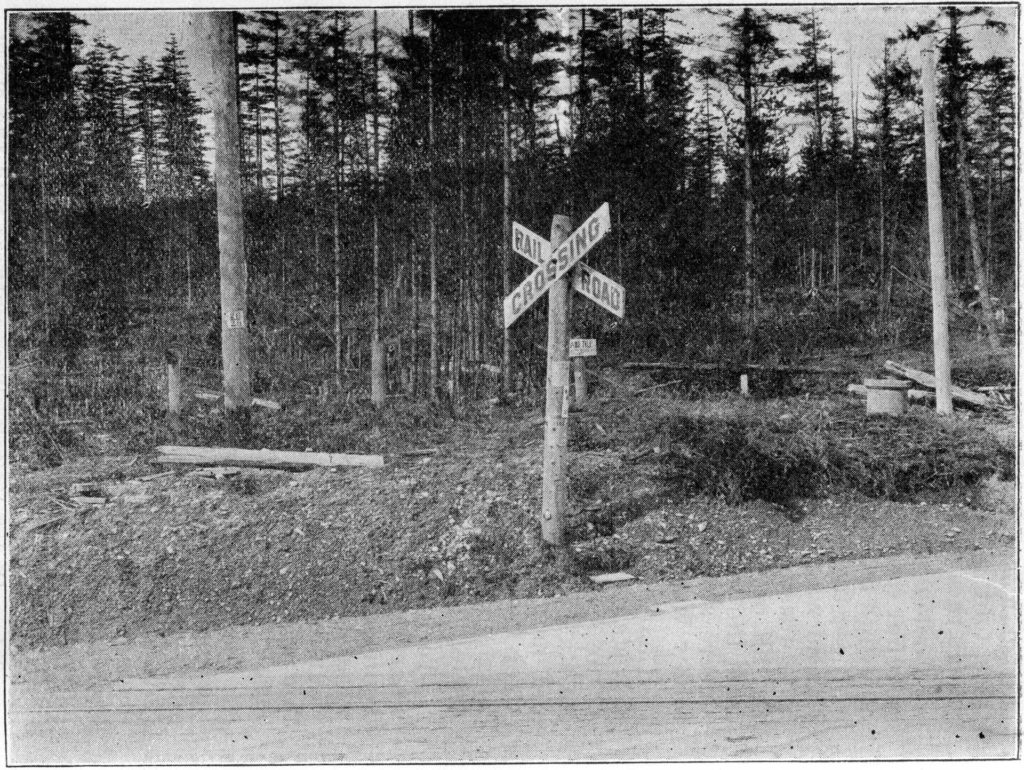

View of Beverly Park, showing County Road.

211

“Rabinowitz was lying on top of me with his head on my leg. I felt my leg getting wet and I reached back to see what it was, and when I pulled my hand away it was covered with blood. He was shot in the back of the brain.”

James McRoden, I. W. W. member who was on the Verona, gave corroborative testimony about the first shot having been from the dock.

James Francis Billings, one of the free speech prisoners, testified that he was armed with a Colts 41 revolver on the Verona, and shortly after the shooting started he went to the engineer of the boat and ordered him to get the Verona away from the dock. He threw the gun overboard on the return trip to Seattle. Black tried to make light of the serious injuries this witness had received at Beverly Park by asking him if all that he received was not a little brush on the shin. The witness answered:

“No sir. I had a black eye. I was beaten over both eyes as far as that is concerned. My arms were held out by one big man on either side and I was beaten on both sides. As Sheriff McRae went past me he said ‘Give it to him good,’ and when I saw what was coming I dropped in order to save my face, and the man on the left hand side kicked me from the middle of my back clear down to my heels, and he kept kicking me until the fellow on the right told him to kick me no more as I was all in. My back and my hip have bothered me ever since.”

Black tried to interrupt the witness and also endeavored to have his answer stricken from the testimony but the judge answered his objection by saying:

“I told you to withdraw the question and you didn’t do it.”

Vanderveer asked Billings the question:

“Why did you carry a gun on the fifth of November?”

“I took it for my own personal benefit,” replied Billings. “I didn’t intend to let anybody beat me up like I was beaten on October 30th in the condition I was in. I was in bad condition at the time.”

212

Harvey E. Wood, an employe of the Jamison Mill Company, took the stand and told of a visit made by Jefferson Beard to the bunkhouse of the mill company on the night of November 4th and stated that at the time there were six automatic shot guns and three pump guns in the place. These were for the use of James B. Reed, Neal Jamison, Joe Hosh, Roy Hosh, Walter S. Downs, and a man named McCortell. This witness had acted as a strikebreaker up until the time he was subpoenaed.

Two of the defendants, Benjamin F. Legg and Jack Leonard, fully verified the story told by Billings.

Leland Butcher, an I. W. W. member who was on the Verona, told of how he had been shot in the leg. When asked why he had joined the I. W. W. he answered:

“I joined the I. W. W. to better my own condition and to make the conditions my father was laboring under for the last 25 years, with barely enough to keep himself and family, a thing of the past.”

Another of the defendants, Ed Roth, who had been seriously wounded on the Verona, gave an unshaken story of the outrage. Roth testified that he had been shot in the abdomen at the very beginning of the trouble and because of his wounded condition and the fact that there were wounded men piled on top of him he had been unable to move until some time after the Verona had left the dock. This testimony showed the absurdity of McRae’s pretended identification of the witness. Roth was a member of the International Longshoremen’s Association and had joined the I. W. W. on the day before the tragedy.

John Stroka, a lad of 18, victim of the deputies at Beverly Park and a passenger on the Verona, gave testimony regarding the men wounded on the boat.

The next witness was Ernest P. Marsh, president of the State Federation of Labor, who was called for the purpose of impeaching the testimony of Mayor Merrill and also to prove that Mrs. Frennette was a visitor at the Everett Labor Temple on the morning

213

of November 5th, this last being added confirmation of the fact that Clyde Gibbons had committed perjury on the stand.

To the ordinary mind—and certainly the minds of the prosecution lawyers were not above the ordinary—the social idealist is an inexplicable mystery. Small wonder then that they could not understand the causes that impelled the next witness, Abraham Bonnet Wimborne, one of the defendants, to answer the call for fighters to defend free speech.

Wimborne, the son of a Jewish Rabbi, told from the witness stand how he had first joined the Socialist Party, afterward coming in contact with the I. W. W., and upon hearing of the cruel beating given to James Rowan, had decided to leave Portland for Everett to fight for free speech. Arriving in Seattle on November 4th, he took passage on the steamer Verona the next day.

Prosecutor Black asked the witness what were the preparations made by the men on the boat.

“Don’t misunderstand my words, Mr. Black,” responded Wimborne, “when I say prepared, I mean they were armed with the spirit of determination. Determined to uphold the right of free speech with their feeble strength; that is, I never really believed it would be possible for the outrages and brutalities to come under the stars and stripes, and I didn’t think it was necessary for anything else.”

“Then when these men left they were determined?” inquired Black.

“Yes, determined that they would uphold the spirit of the Constitution; if not, go to jail. There were men in Everett who would refuse the right of workingmen to come and tell the workers that they had a way whereby the little children could get sufficient clothing, sufficient food, and the right of education, and other things which they can only gain—how? By organizing into industrial unions, sir, that is what I meant. We do not believe in bloodshed. Thuggery is not our method. What can a handful of workers do against the mighty forces

214

of Maxim guns and the artillery of the capitalist class?”

“Did you consider yourself a fighting member?” questioned Black.

“If you mean am I a moral fighter? yes; but physically—why, look at me! Do I look like a fighter?” said the slightly built witness.

“Did you or did you not expect to go to jail when you left Portland?” asked the prosecutor.

“My dear Mr. Black, I didn’t know and I didn’t care!” responded Wimborne with a shrug of his shoulders.

Wimborne joined the I. W. W. while in the Everett County Jail.

Michael J. Reilley, another of the defendants, testified as to the firing of the first shot from the dock and also gave the story of the death of Abraham Rabinowitz. Vanderveer asked him the question:

“Do you know why you are a defendant?”

“Yes, sir,” replied Reilley, “because I didn’t talk to them in the city jail in Seattle. I was never picked out.”

Attorney H. D. Cooley was recalled to the stand and was made to admit that he was a member of the Commercial Club and a citizen deputy on the dock November 5th. He was asked by Vanderveer:

“Did you see any guns on the dock?”

“Yes sir.”

“Did you see any guns fired on the dock?”

“Yes sir.”

“Did you see any guns fired on the boat?”

“No sir.”

“Did you see a gun on the boat?”

“I did not.”

“You were in full view of the boat?”

“I was.”

Yet the ethics of the legal profession are such that this attorney could justify his actions in laboring for months in an endeavor to secure, by any and all means, the conviction of the men on the boat!

Defendant Charles Black testified that McRae

215

dropped his hand to his gun and pulled it just as one of the deputies fired from a point just behind the sheriff. Black ran down the deck and into the cabin, passing in front of the windows from which the deputies had sworn that heavy firing was going on.

Leonard Broman, working partner with Abraham Rabinowitz, then took the stand and told his story. When asked what were the benefits he received from having joined the I. W. W., the witness replied:

“They raised the wages and shortened the hours. Before I joined the I. W. W. the wages I received in Ellis, Kansas, was $3.00 for twelve hours and last fall the I. W. W. got $3.50 for nine hours on the same work.”

Ex-deputy Charles Lawry told of various brutalities at the jail and also impeached McRae’s testimony in many other particulars.

Dr. Grant Calhoun, who had attended the more seriously injured men who were taken from the Verona on its return to Seattle, told of the number and nature of the wounds that had been inflicted. On eight of the men examined he had found twenty-one serious wounds, counting the entrance and exit of the same bullet as only one wound. Veitch conducted no cross-examination of the witness.

Joe Manning, J. H. Beyers, and Harvey Hubler, all three of them defendants, gave their testimony. Manning told of having been seated in the cabin with Tracy when the firing commenced, after which he sought cover behind the smokestack and was joined by Tracy a moment later. Beyers identified Deputy Bridge as having stood just behind McRae with his revolver drawn as tho firing when the first shot was heard. This witness also corroborated the story of Billings in regard to demanding that the engineer take the boat away from the dock. Hubler verified the statements about conditions on the Verona and also told of being taken from his jail cell by force on an order signed by detective McLaren in an attempt to have him discharge the defense attorneys and accept an alleged lawyer from Los Angeles.

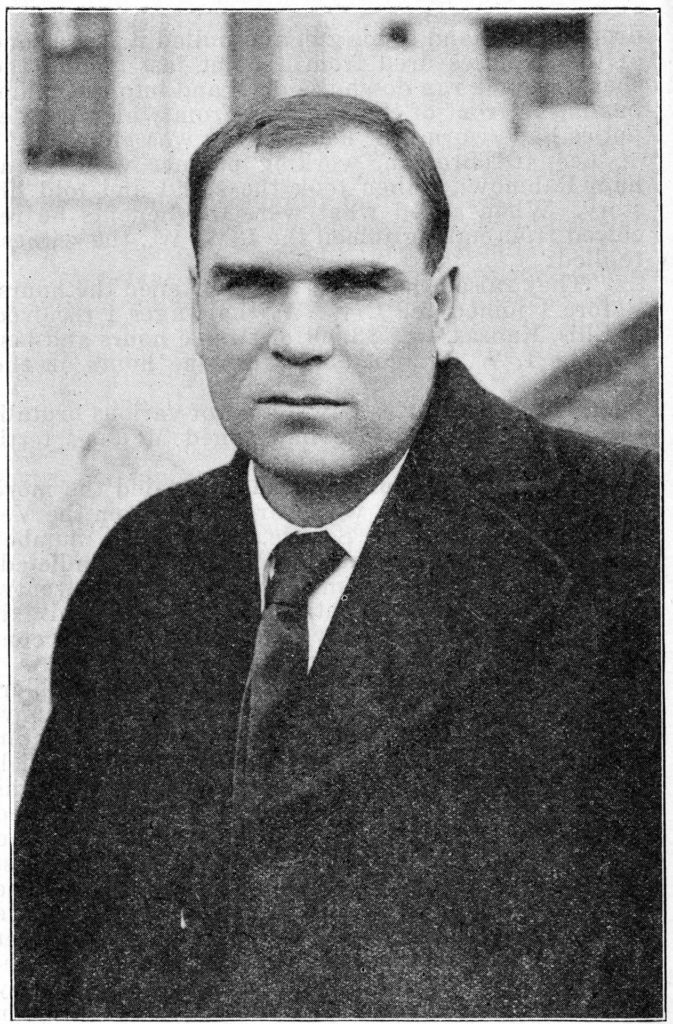

THOMAS H. TRACY

217

Harry Parker and C. C. England told of injuries sustained on the Verona, and John Riely stated there was absolutely no shooting from the cabin windows, that being impossible because the men on the boat had crowded the entire rail at that side.

Jerry L. Finch, former deputy prosecuting attorney of King County, gave impeaching testimony against Wm. Kenneth and Charles Tucker. Cooley asked this witness about his interviews with the different state’s witnesses:

“If you talked with all of them, you would probably have something on all of them?”

The judge would not let Finch answer the question, but there is no doubt that Cooley had the correct idea about the character of the witnesses on his side of the case.

In detailing certain arrests Sheriff McRae had claimed that men taken from the shingleweavers’ picket line were members of the I. W. W. B. Said was one of the men so mentioned. Said took the witness stand and testified that he was a member of the longshoremen’s union and was not and had not been a member of the I. W. W.

J. G. Brown, president of the International Shingleweavers’ Union, testified that the various men arrested on the picket line in Everett were either members of the shingle weavers’ union or else were longshoremen from Seattle, none of the men named by McRae being members of the I. W. W. The testimony of Brown was also of such a nature as to be impeaching of the statements of Mayor Merrill on the witness stand.

Charles Gray, Robert Adams, and Joe Ghilezano, I. W. W. men on the Verona, then testified, Adams telling of having been shot thru the elbow, and Ghilezano giving the details of the way in which his kneecap had been shot off and other injuries received.

The murderous intentions of the deputies were further shown by the testimony of Nels Bruseth, who ran down to the shore to launch a boat and

218

rescue the men in the water. He was stopped in this errand of mercy by the deputies.

Civil Engineer F. Whitwith, Jr., of the firm of Rutherford and Whitwith, surveyed the dock and the steamer Verona and made a report in court of his findings. His evidence clearly showed that there was rifle, shotgun and revolver fire of a wild character from the interior of the warehouses and from many points on the dock. He stated that there were one hundred and seventy-three rifle or revolver bullet marks, exclusive of the B-B and buckshot markings which were too numerous to count, on the Verona, these having come from the dock, the shore, and the Improvement Dock to the south. There were sixteen marks on the boat that appeared as tho they might have been from revolver fire proceeding from the boat itself. There were also small triangular shaped gouges in the planking of the dock, the apex of the triangles indicating that bullets had struck there and proceeded onward from the Klatawa slip to the open space on the dock where deputies had been stationed. The physical facts thus introduced were incontrovertible.

Defendant J. D. Houlihan gave positive testimony to the effect that he had not spoken privately with “Red” Doran in the I. W. W. hall on the morning of November 5th, that he had received no gun from Doran or anyone else, that he did not have the conversation which Auspos imputed to him, that he had no talk with Auspos on the return trip. All efforts to confuse this witness failed of their purpose.

In verification of the testimony about deputies firing on the Verona from the Improvement Company Dock the defense brought Percy Walker upon the stand. Walker had been cruising around the bay in a little gasoline launch and saw men armed with long guns, probably rifles or shotguns, leaning over a breastwork of steel pipes and firing in the direction of the Verona.

Lawrence Manning, Harston Peters, and Ed. J. Shapeero, defendants, told their simple straightforward stories of the “battle.” Peters stated that

219

as he lay under cover and heard the shots coming from the dock he “wished to Christ that he did have a gun.” Shapeero told of the wounds he had received and of the way the uninjured men cared for the wounded persons on the boat.

Mrs. Joyce Peters testified that she had gone to Everett on the morning of November 5th in company with Mrs. Lorna Mahler. The reason she did not go on the Verona was because the trip by water had made Mrs. Mahler ill on previous occasions. She saw Mrs. Frennette in Everett only when they were on the same interurban car leaving for Seattle after the tragedy.

Albert Doninger, W. B. Montgomery and Japheth Banfield, I. W. W. men who were on the Verona, all placed the first shot as having come from the dock immediately after the sheriff had cried out “You can’t land here.”

N. Inscho, Chief of Police of Wenatchee, testified that during the time the I. W. W. carried on their successful fight for free speech in his city there were no incendiary fires, no property destroyed, no assaults or acts of violence committed, and no resistance to arrest.

H. W. Mullinger, lodging house proprietor, John M. Hogan, road construction contractor, Edward Case, railroad grading contractor, William Kincaid, alfalfa farmer, and John Egan, teamster, all of North Yakima and vicinity, were called as character witnesses for Tracy, the defendant having worked with or for them for a number of years.

The defense followed these witnesses with Oscar Carlson, the passenger on the Verona who had been fairly riddled with bullets. Carlson testified that he was not and never had been a member of the I. W. W., that he had gone to Everett with his working partner, Nordstrom, as a sort of an excursion trip, that he had purchased a one way ticket which was taken up by the captain after the boat had left Seattle, that he intended returning by way of the Interurban, and that the men on the boat were orderly and well behaved. He told of having gone to the

220

very front of the boat as it pulled into Everett from which point he heard the first shot, which was fired from the dock. He fell immediately and while prostrate was struck with bullet after bullet. He then told of having entered suit against the Vashon Navigation Company for $50,000.00 on account of injuries received. Robert C. Saunders, of the law firm of Saunders and Nelson, then testified that he was handling the case for Carlson and had made out the affidavit of complaint himself and was responsible for the portion that alleged that a lawless mob were on the boat, Carlson having made no such statement to him at any time.

Charles Ashleigh was recalled to the stand to testify to having telephoned to the Seattle newspapers on November 4th, requesting them to send reporters to Everett the next day. He was followed on the stand by John T. Doran, familiarly known as “Red” on account of the color of his hair. Doran stated that he was the author of the handbill distributed in Everett prior to the attempted meeting of November 5th. He positively denied having given a gun to Houlihan or anyone else on November 5th. Upon cross-examination he said that he was in charge of the work of checking the number of men who went on the Verona to Everett, and had paid the transportation of the men in a lump sum.

As the next to the last witness on its side of the long-drawn out case the defense placed on the stand the defendant, Thomas H. Tracy. The witness told of having been one of a working class family, too large to be properly cared for and having to leave home and make his own way in the world before he was eleven years old. From that time on he had followed farming, teaming and construction work in all parts of the west, his bronzed appearance above the prison pallor giving evidence of his outdoor life.

Tracy told of having been secretary of the I. W. W. in Everett for a short time, that being the only official position he had ever held in the organization. He explained his position on the boat at the time

221

it docked, stating that the first shot apparently came from the dock and struck close to where he was sitting. Immediately the boat listed and threw him away from the window, after which he sought a place of safety behind the smokestack. He denied having been in any way a party to a conspiracy to commit an act of violence, or to kill anyone.

“You are charged here, Mr. Tracy,” said Vanderveer, “with having aided and abetted an unknown man in killing Jefferson Beard. Are you guilty or not guilty?”

“I am not guilty,” replied Tracy without a trace of emotion.

The cross-questioning of the defendant in this momentous case was conducted by citizen-deputy Cooley. His questions to the man whom he and his fellow conspirators on the dock had not succeeded in murdering were of the most trivial nature, clearly proving that arch-sleuth McLaren had been unable to discover or to manufacture anything that would make Tracy’s record other than that of a plain, unassuming, migratory worker.

“Where did you vote last?” asked Cooley.

“I never voted,” responded Tracy.

“Never voted in your life?” queried Cooley.

“No!” replied the defendant who for the time represented the entire migratory class. “I was never in one place long enough!”

Then, acting on the class theory that it is an honor to be a “globe-trotter” but a disgrace to be a “blanket-stiff,” the prosecutor brought out Tracy’s travels in minute detail. This examination of the railroad construction worker brought home to the listeners the truth of the little verse:

“He built the road;

With others of his class he built the road;

Now o’er its weary length he packs his load,

Chasing a Job, spurred on by Hunger’s goad,

He walks and walks and walks and walks,

And wonders why in Hell he built the road!”

Then there hobbled into the court room on crutches a stripling with an empty trouser leg, his face

222