Hugo Gerlot

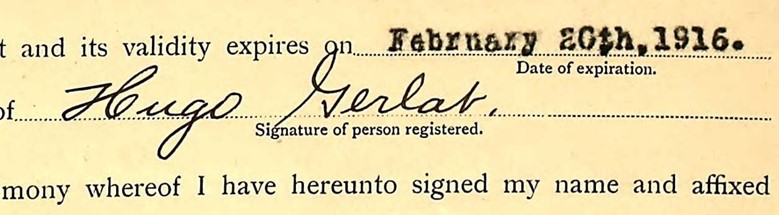

from United States Consulate in London.

Hugo E. Gerlat (1891- 1916) was the oldest of nine children born to Mathias (Matthew) and Caroline Emilie Hauchwitz Gerlat. Hugo’s parents may have been ethnic Germans in Russia from Suwalki gubernia. Mathias emigrated in 1886, Emilie emigrated in 1871, and they were married in 1890 in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, where Hugo was born 19 December 1891. There’s a good chance that the family lived in a German neighborhood and that Hugo spoke both German and English.

Between 1893-1895, the family moved to Milwaukee, where Matthew Gerlat was listed variously as a laborer, cabinet maker, and painter and finisher in Milwaukee city directories.

In 1908, the Milwaukee city directory lists Hugo as a laborer. He then spent some time as a meter man and by 1909, he was listed as an electrician working for the Electric Light Company, also known as the Milwaukee Electric Railroad & Light Company (TMER&L Co.) in 1910. He lived with his family of origin as they moved to new rental houses in the same area of the city until late 1912 or early 1913, when he left home.

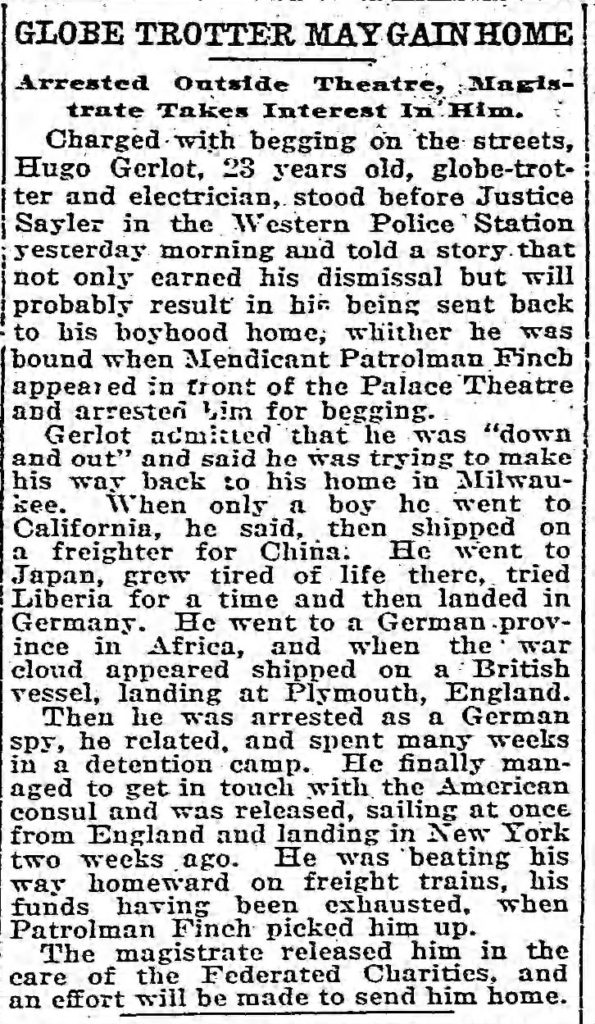

In 1915, Hugo, whose last name was spelled Gerlot, was taken before a Baltimore judge after being arrested for begging (“Globe Trotter May Gain Home”). He said he had left home for California, then shipped out on a freighter bound for China, leaving the United States on 21 January 1914. He traveled to Japan, Liberia, and Germany, then went to a German province in Africa. With war on the horizon, he shipped out on a British vessel and landed at Plymouth, England. Suspected of being a German spy, he spent weeks in a detention camp until he managed to contact the American consul. According to the U.S. Consular Record in London, Hugo arrived in London on December 7, 1914, where he was staying at Mackenzies Hotel while recovering from malaria contracted in Africa.

Hugo returned to the United States on 13 March 1915 aboard the RMS Arabic, a passenger ship of the White Star Line that served the Liverpool-New York and Liverpool-Boston routes. (Five months later on 19 August 1915, the German submarine U-24 torpedoed Arabic, and the ship sank in 9 minutes, the first White Star Line ship to be lost in World War I.)

As the Baltimore Sun reported, two weeks after arriving in the United States, Hugo was arrested outside Baltimore’s Palace Theatre, and when the judge heard his story, he was released and sent back to Milwaukee. Hugo lived in his parents’ home at 1030 Fifteenth Street in Milwaukee with his eight younger siblings, ages 22 to 2. He was listed in the 1915 phone directory as an electrician but he left home again in July, possibly joining a crew on a Great Lakes carrier. If so, he would have visited the Lake Carriers’ Association office to find work, probably at the Association’s assembly room at 280 West Water Street in Milwaukee.

The Association was a voluntary alliance of steamship companies. On September 1, 1880 Great Lakes vessel owners founded the Cleveland Vessel Owners’ Association which, with other similar organizations worked to regulate Great Lakes shipping. In 1885 the Lake Carrier’s Association was founded by local vessel owners in Buffalo, New York and in 1892, the Cleveland Vessel Owners’ Association, as well as others, merged with the original Association from Buffalo.

In 1903 the Association was incorporated under the laws of West Virginia, and in that same year entered into its first agreement with the Lake Seamen’s Union. The most important—indeed the dominating—member of the Association was the Pittsburg Steamship Co., a subsidiary of the United States Steel Corporation. Though the Association had negotiated with several unions including the International Seamen’s Union of America, on April 9, 1908, the Association voted unanimously to adopt the open shop, saying, “That the owners of ships on the Great Lakes do now declare that the open-shop principle be adopted and adhered to on our ships” (Brissenden, Employment System of the Lake Carriers’ Association, p. 36).

Hugo would have signed an Association agreement to get Association credentials, which included a pledge that read,

From engagement on any vessel included in the membership of the Lake Carriers’ Association he will perform all his lawful duties regardless of whether any officer or member of the crew may or may not be member of any union or association, failure in which shall be good ground in the final discretion of the Lake Carriers’ Association for revocation of this card (Brissenden, Employment System of the Lake Carriers’ Association, p. 42).

Once accepted, Hugo would have paid $1 annual dues and received his certificate/identification card and discharge book. The identification card listed a description of the card holder to stop attempts to give or sell credentials, including address, place of birth, age, height, and complexion.

Once Hugo was assigned a ship at the shipping office, he, like others who were not officers, would give his discharge book to a ship’s master or chief engineer. The person holding the credentials would essentially grade the sailor’s performance and return the book when the sailor left the ship. Without a discharge book and a good grade, a sailor would have a difficult time finding his next job on a Great Lakes ship.

When Hugo was killed aboard the Verona on 5 November 1916, his Lake Carriers’ Association card was used to identify him. But there’s no mention of a discharge book. He may have lost it or left his place aboard ship before the end of the season in mid-December. This wouldn’t have been surprising as turnover rates on Association vessels was very high. For example, in 1913, there were on average, nine changes made to keep each deck hand job filled; six changes for each porter’s job; six for each fireman’s; four for each wheelman’s; four for each watchman’s; and four for each (“second”) cook’s (Brissenden, Employment System of the Lake Carriers’ Association, p. 31).

There’s also no mention of whether Hugo was carrying an IWW membership card. There’s little evidence that Hugo was an IWW other than the IWW claiming him as a member. According to the Industrial Worker, the men aboard the Verona included members of the International Longshoremens’ Association, the Seamen’s Union, Auxiliary Truckers’ Union, and other labor organizations as well as the IWW. Some men didn’t claim union membership but were traveling to Everett to look for work and others were spending a beautiful fall day taking a free boat trip.

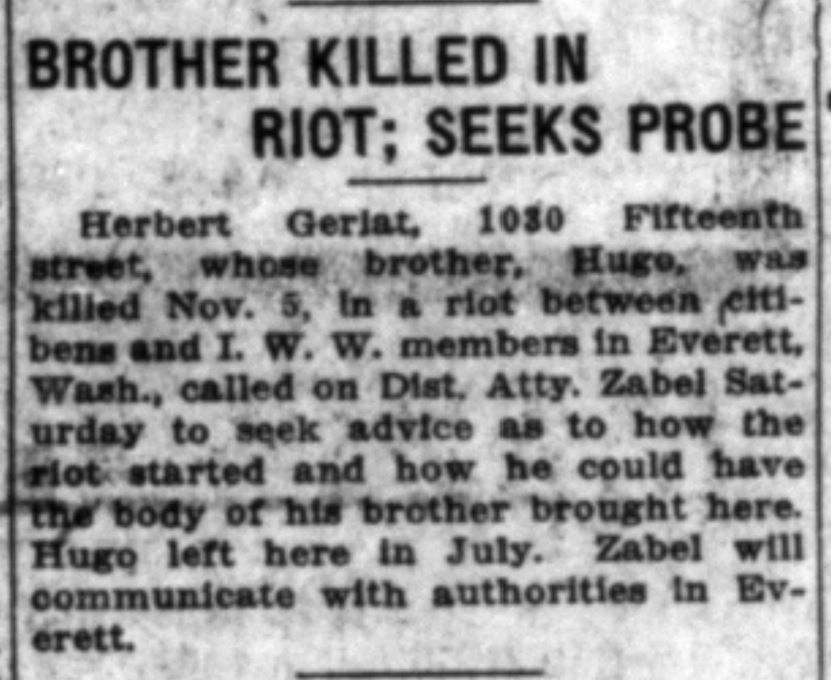

But Hugo’s body was not returned to Milwaukee. He, along with Felix Baran and John Looney, were buried on 23 November 1916 at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Seattle. These three men were later memorialized by the local Russian Colony and the IWW. The local Russian Colony spelled his name correctly while the IWW did not.

Hugo’s parents, Emilie and Mathias Gerlat, divorced in 1920, with Matt ordered to pay attorneys and court fees as well as $10 per week maintenance and support of their three minor children. A year later, Matt committed suicide by drinking carbolic acid.