James Kelly

James Whiteford (1888-1932) was born in Rochester, New York in May 1888 to James Whiteford (1863-1936) and Jeanette/Janet Penman (1867-1947). He had three younger siblings: John Penman (1889-1962), Alexander Thompson (1890-1983), and Margaret (1892-1910?).

It appears Jennie Whiteford took her oldest and youngest children back to Scotland, returning in 1894 when James was age 6 and Maggie was age 11 months. There isn’t much about Jim available from this point, other than census records showing he was in school as were his siblings. Later information involves crime and alcohol. On page 9 of the 16 August 1902 Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 14-year-old James Whiteford “was found almost insensible from the effects of liquor yesterday forenoon at the corner of Lake and Glenwood avenues.”

In 1905, while 17, working as a teamster in Rochester and still living with his parents, Jim enlisted in the military on 5 December. He was 22 years and 8 months, inducted, and assigned to the Coastal Artillery. He was discharged 15 April 15 1906, though his enlistment was supposed to be for three years. Quite possibly the military authorities found out he was too young to serve.

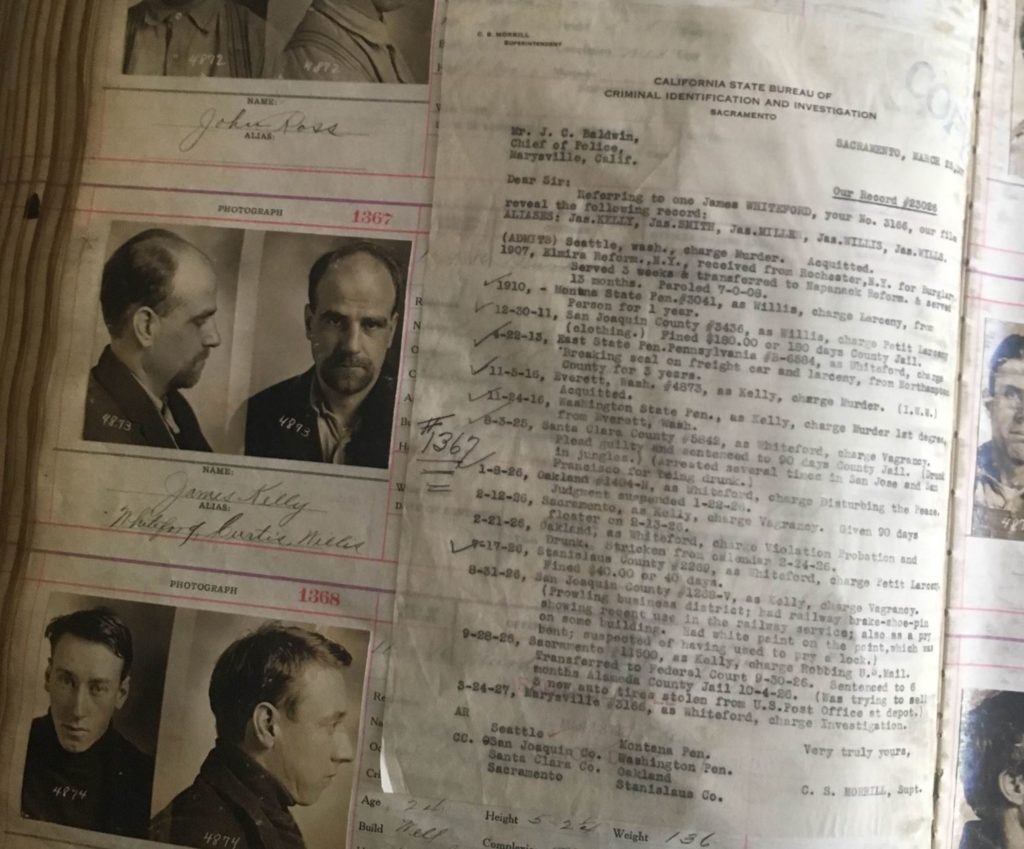

California State Bureau of Criminal Identification and Investigation shared Jim’s arrests and prison records typed on a single page pasted into the arrest book at Everett. The page lists known charges from 1907 to 1927, and aliases that include James Kelly, James Smith, James Miller, James Willis, and James Wills.

About a year after he was released and still using the name James Willis, Jim was arrested with Thomas Kelly on 29 December 1911 in Stockton, California, for petit larceny. He and Kelly grabbed a bunch of merchandise, including trousers and shoes, and were escaping when caught. Unable to pay a $100 fine, they were sent to work on the chain gang for $1 per day (“Are New Working”).

Jim was arrested with Frank Garvin for vagrancy and after serving thirty days, both were arrested again for stealing ten pairs of lace curtains from a railroad car (“Another Charge”). They were charged with breaking the seal on a freight car and larceny. Whiteford was sentenced to a minimum of 3 and maximum of 4 years and fined $1.00 (“Criminal Court in Session at Easton”).

On 22 April 1913, as James Curtis, Whiteford, Willis/Willis, Jim arrived at Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) in Pennsylvania and given number #B-6584. He’s listed as a Protestant who works as a cook who left home at the age of 12, can read and write, smokes, drinks, chews, swears, and is occasionally intemperate. He had 45 cents in his pocket when arrested. At ESP, he worked making stockings, earning $56.89 and receiving $32.84 when released on parole on 4 April 1916. The record says he planned to go his mother Jennie’s home at 4 Leavenworth St., Rochester, NY. Instead, he disappeared in June 1916.

About six months later, he was arrested after the shootout at the Everett City Dock. The arrest book reports that he worked as a cook and was transferred from Seattle to the Snohomish County Jail as #4873 on November 15, 1916. The book also lists his age as 36, though he was closer to 28.

By April 1, 1917, after the state had rested and the defense had not yet begun during the Tracy trial, Jim was recognized and returned to ESP to finish serving his sentence. This was despite being identified by Sheriff McRae as one of the men shooting from the Verona.

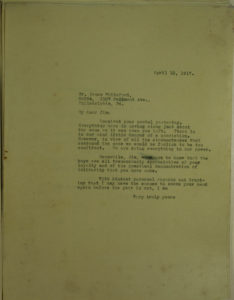

Smith praises Jim for choosing to return to ESP instead of agreeing to talk in exchange for dropping all charges against him, praise echoed from a letter from the defense team dated 10 April 1917, “Meanwhile, Jim, want you to know that the boys are all tremendously appreciative of your loyalty and of the practical demonstration of Solidarity that you have made” (Bert Carpenter papers, Joseph A. Labadie Collection, Special Collections Library, University of Michigan).

There’s nothing new about jailhouse informants. There’s no way to know if Jim had crucial information or would be willing to lie to help prosecutors get a conviction. And I have no way of knowing for certain, but perhaps this was the most principled stand Jim Whiteford every made by choosing not to take the easier path of informant.

Jim returned to ESP with $29, buttons, and a Canadian dime in his pockets on 7 April 1917. He served 11 months and 23 days and was paid $65.84 40 when released on 1 March 1918. Documents show he planned to go to Chicago, the headquarters of the IWW General Executive Board (GEB).

There is a gap of seven years between his release and any documentation about him that I could find. He may have re-joined the military as the United States entered World War I on 6 April 1917, or perhaps passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919 helped him achieve sobriety. Perhaps he worked with the IWW and that kept him out of trouble.

California State Bureau of Criminal Identification and Investigation report says that on 3 August 1925 in Santa Clara County, Jim was given #5842 as Whiteford, charged with vagrancy for being drunk in the hobo jungles. He pled guilty and sentenced to 90 days County Jail. The report mentions that he was arrested several times in San Jose and San Francisco for being drunk.

Jim’s younger brother John was living in Los Angeles, California and working in the motion picture industry at about this same time. John became known as Blackie Whiteford and appeared in 275 films between 1928 and 1962. He was best known for appearing in 28 films with The Three Stooges between 1936 and 1956. His last appearance was as a townsman in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

Then came a series of arrests and time in jail for vagrancy, drunkenness, and burglary. On 28 September 1926, in Sacramento, he’s charged with robbing the U.S. Mail and sentenced to 6 months at Alameda County Jail. He was caught trying to sell 3 new auto tires stolen from the U.S. Post Office depot.

On Valentine’s Day, 1930, Whiteford, described as a transient war veteran, had his 30-day sentence for vagrancy suspended because Judge D.L. Bass thought Jim’s fluffy collie puppy was cute (“Friendly Puppy Wins Freedom for Master”). On 27 December 1930, he received a beating with a baseball bat after being caught trying to steal from someone at an auto camp (“Whiteford Pleads Not Guilty to Burglary”).

Jim’s death is sad and sordid. On 18 April 1932, an unidentified itinerant, a “canned heat” addict, was found in his jail cell dead of acute alcohol poisoning. He and another hobo, Pat Hogan, had been hauled in from a nearby hobo jungle, both drunk and expected to sleep it off. On the dead man’s left arm was a tattoo of a woman’s figure and the word “Mother.” On his right was a woman’s head and two numbers: No. A—25554425 and Serial B—32953, both believed to be Army identification numbers (“Poison ‘Alky’ Kills Hobo in S.R. Jail Cell”).

Jim was identified on 15 May 1932, with The Press Democrat of Santa Rosa, California, reporting that he was a veteran of World War I, with 16 months of service with the quartermaster. I haven’t been able to confirm this, though I know he served in the Army 1905-1906 and he was given a military funeral in Rochester. His parents were not told of the circumstances of their son’s death (“Itinerant Who Died in Jail is Identified”).