115

CHAPTER V.

BEHIND PRISON BARS

“One of the greatest sources of social unrest and bitterness has been the attitude of the police toward public speaking. On numerous occasions in every part of the country the police of cities and towns have, either arbitrarily or under the cloak of a traffic ordinance, interfered with or prohibited public speaking, both in the open and in halls, by persons connected with organizations of which the police or those from whom they receive their orders did not approve. In many instances such interference has been carried out with a degree of brutality which would be incredible if it were not vouched for by reliable witnesses. Bloody riots frequently have accompanied such interference, and large numbers of persons have been arrested for acts of which they were innocent or which were committed under the extreme provocation of brutal treatment by police or private citizens.

“In some cases this suppression of free speech seems to have been the result of sheer brutality and wanton mischief, but in the majority of cases it undoubtedly is the result of a belief by the police or their superiors that they were ‘supporting and defending the Government’ by such invasion of personal rights. There could be no greater error. Such action strikes at the very foundation of government. It is axiomatic that a government which can be maintained only by the suppression of criticism should not be maintained. Furthermore, it is the lesson of history that attempts to suppress ideas result only in their more rapid propagation.”

The foregoing is the view of the Industrial Relations Commission as it appears on page 98 and 99 of Volume One of their official report to the United States Government.

116

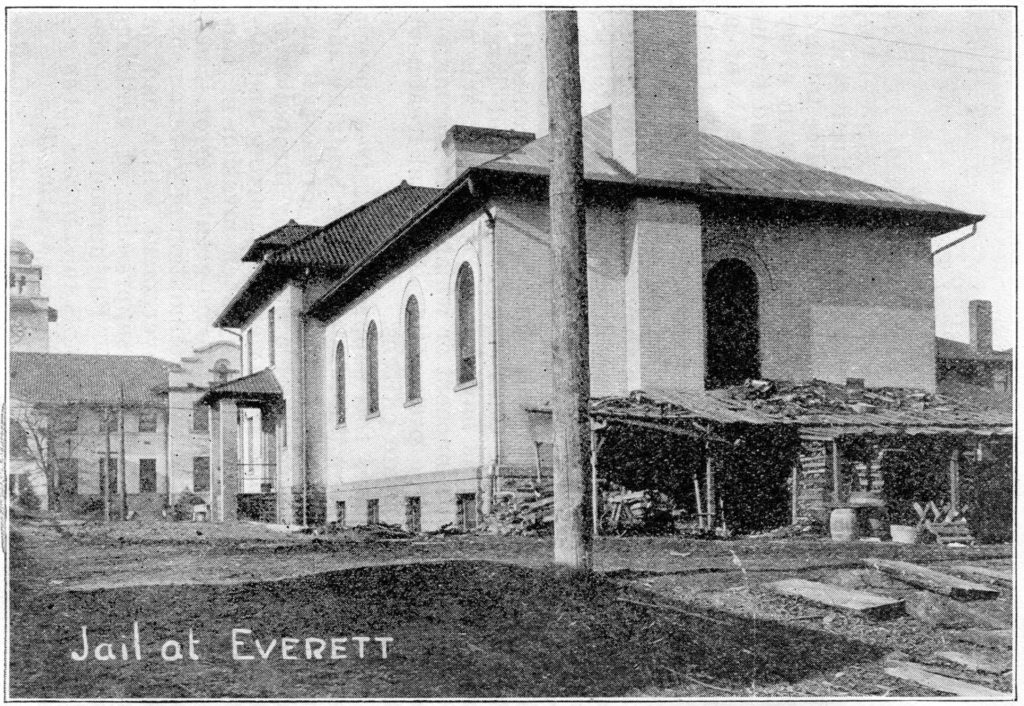

Jail at Everett

117

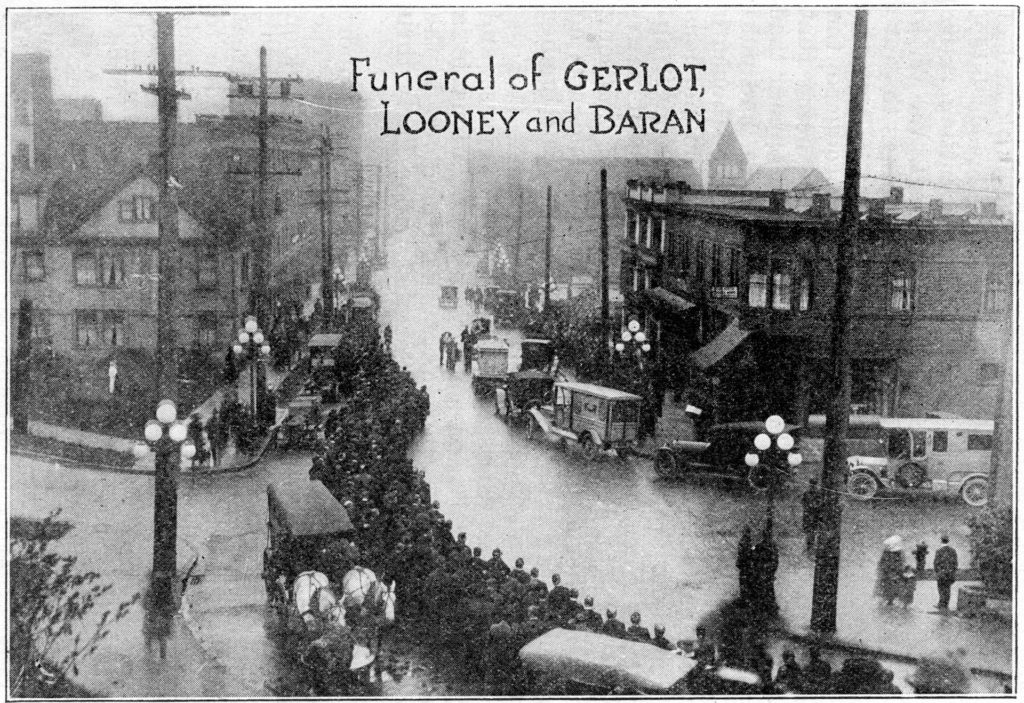

The growth of a public sentiment favorable to the Industrial Workers of the World was clearly shown on November 18th, at which time the bodies of Felix Baran, Hugo Gerlot and John Looney were turned over to the organization for burial. Gustav Johnson had already been claimed by relatives and a private funeral held, and the body of Abraham Rabinowitz sent to New York at the request of his sister.

Thousands of workers, each wearing a red rose or carnation, formed in line at the undertaking parlors and then silently marched four abreast behind the three hearses and the automobiles containing the eighteen women pall bearers and the floral tributes to the martyred dead.

To the strains of the “Red Flag” and the “Marseillaise” the grim and imposing cortege wended its way thru the crowded city streets, meeting with expressions of sorrow and sympathy from those who lined the sidewalk. Delegations of workers from Everett, Tacoma, and other Washington cities and towns were in line, and a committee from Portland, Ore., brought appropriate floral offerings. The solidarity of labor was shown in this great funeral procession, by all odds the largest ever held in the Northwest.

Arriving at the graveside in Mount Pleasant cemetery the rebel women reverently bore the coffins from the hearses to the supporting frame, surrounded by boughs of fragrant pine, above the yawning pit. A special chorus of one hundred voices led the singing of “Workers of the World, Awaken,” and as the song died away Charles Ashleigh began the funeral oration.

Standing on the great hill that overlooks the whole city of Seattle, the speaker pointed out the various industries with their toiling thousands and referred to the smoke that shadowed large portions of the view as the black fog of oppression and ignorance which it was the duty of the workers to dispel in order to create the Workers’ Commonwealth. The entire address was marked by a simple note of

118

resolution to continue the work of education until the workers have come into their own, not a trace of bitterness evincing itself in the remarks. Ashleigh called upon those present never to falter until the enemy had been vanquished. “Today,” he said, “we pay tribute to the dead. Tomorrow we turn, with spirit unquellable, to give battle to the foe!”

As the notes of “Hold the Fort!” broke a moment of dead silence, a shower of crimson flowers, torn from the coats of the assembled mourners, covered the coffins and there was a tear in every eye as the bodies slowly descended into their final resting place. As tho loath to leave, the crowd lingered to sing the “Red Flag” and “Solidarity Forever.” Those present during the simple but stirring service were struck with the thought that the class struggle could never again be looked upon as a mere bookish theory, the example of those who gave their lives in the cause of freedom was too compelling a call to action.

But the imperious exactions of the class war left no time for mourning, and ere the last man had left the graveside the first to go was busily spreading the news of an immense mass meeting to be held in Dreamland Rink on the next afternoon. At this meeting five thousand persons from all walks of life gathered to voice their protest against the Everett outrage and to demand a federal investigation. The labor unions, the clergy, public officials and the general citizenry, were represented by the speakers. This was the first of many mass meetings held by the aroused and indignant people of Seattle until the termination of the case.

119

Funeral of Gerlot, Looney and Baran

The “kept” press carried on a very bitter campaign against the I. W. W. for some few days after the dock tragedy, but dropped that line of action when the public let them understand that they were striking a wrong note. Thereafter their policy was to ignore, as far as possible, the entire affair. Practically the only time this rule was broken was in the printing of the song “Christians At War” by John F. Kendrick, taken from the I. W. W. song book.

120

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer gave a photographic reproduction of the cover page of the book and of the page containing the song. The obvious intent was to have people think that this cutting satire was an urge for the members of the I. W. W. to do in times of peace those inglorious things that are eminently respectable in times of war. Later the Times, and several other papers, reproduced the same cover and song, the only change being that certain words were inked out to make it appear that the song was obscene. And tho the P.—I. had published the song in full the Times placed beneath their garbled version these words, “The portions blotted out are words and phrases such as never appear in The Times or in any other decent newspaper.” The simultaneous appearance of this song in a number of papers was merely a coincidence, no doubt; there is no reason to believe that the lumber trust inspired the attack!

Allied as usual with the capitalist press and “stool pigeons” and employers’ associations in a campaign to discredit the workers involved in the case, was the moribund Socialist Labor Party thru its organ, the Weekly People.

The entire I. W. W. press came to the support of the imprisoned men as a matter of course. The Seattle Union Record and many other craft union papers, realizing that an open shop fight lay back of the suppression of free speech, also did great publicity work. But no particular credit is due to those “labor leaders” who, like J. G. Brown, president of the Shingle Weavers’ Union, grudgingly gave a modicum of assistance under pressure from radicals in their respective organizations.

The Northwest Worker of Everett deserves especial praise for its fearless and uncompromising stand in the face of the bitterest of opposition. This paper had practically to suspend publication because of pressure the lumber trust brought to bear on the firm doing their printing. This, with the

121

action recorded in the minutes of the Commercial Club, “decided to go after advertisements in labor journals and the Northwest Worker,” shows that a free press is as obnoxious to the lumber lords as are free speech and free assembly.

It scarcely needs noting that the International Socialist Review rendered yeoman service, as that has been its record in all labor cases since the inception of the magazine. Several other Socialist publications, to whom the class struggle does not appear merely as a momentary quadrennial event, also did their bit. Diverse foreign language publications, representing varying shades of radical thought, gave to the trial all the publicity their columns could carry.

Just why seventy-four men were picked as prisoners is a matter of conjecture. Probably it was because the stuffy little Snohomish county jail could conveniently, to the authorities, hold just about that number. The men were placed four in a cell with ten cells to each tank, there being two tanks of steel resting one above the other. Even with all the windows thrown open the ventilation was so poor that the men were made ill by the foul air.

For almost two full months after being transported to Everett the men were held incommunicado; were not allowed to see papers or magazines or to have reading matter of any description; were subjected to the brutalities of Sheriff McRae and other jail officials who had been prominent in previous outrage and participants in the massacre at the dock; and were fed on the vilest prison fare. Mush was the principal article of diet; mush semi-cooked and cold; mush full of mold and maggots; mush that was mainly husks and lumps that could not be washed down with the pale blue prison milk; mush—until the prisoners fitfully dreamed of mush and gagged at the mere mention of the word. Finding themselves slowly starving the men decided that it were better to complete the job at once rather than to linger in misery. A hunger strike was

122

declared! Meal after meal—or mush after mush—passed and the men refused to eat. Those who were thought to be leaders in the miniature revolt were thrown in the blackhole where there was neither light nor fresh air. Still the men refused to eat, so the authorities were forced to surrender and the men had something to eat besides mush.

Great discomfort was experienced by the prisoners from having to sleep on the cold steel floors of the unheated cells during the chill November nights. Deciding to remedy the condition they made a demand for mattresses and blankets from the authorities, not a man of them being willing to have the Defense Committee purchase such supplies. The needed articles were refused and the men resorted to a means of enforcing their demands known as “building a battleship.”

With buckets and tins, and such strips of metal as could be wrenched loose, the men beat upon the walls, ceilings, and floors of the steel tanks. Those who found no other method either stamped on the steel floors in unison with their fellows, or else removed their shoes to use the heels to beat out a tattoo. To add to the unearthly noise they yelled concertedly with the full power of their lungs. Three score and ten men have a noise-making power that words cannot describe. The townspeople turned out in numbers, thinking that the deputies were murdering the men within the jail. The battleship construction workers redoubled their efforts. Acknowledging defeat, the jail officials furnished the blankets and mattresses that had been demanded.

A few days later the men started their morning meal only to find that the mush was strongly “doped” with saltpeter and contained bits of human manure and other refuse—the spite work, no doubt, of the enraged deputies. Another battleship was started. This time the jailers closed all the windows in an effort to suffocate the men, but they broke the glass with mop-handles and continued the din. As

123

before, the deputies were defeated and the men received better food for a time.

On November 24th an official of the State Board of Prisoners took the finger prints and photographs of the seventy-four men who were innocent until proven guilty under the “theory” of law in this country, and, marking these Bertillion records with prison serial numbers, sent copies to every prison in the United States. In taking the prints of the first few men brute force was used. Lured from their cells the men were seized, their hands screwed in a vise, and an imprint taken by forcibly covering their hands with lampblack and holding them down on the paper. When the others learned that some had thus been selected they voted that all should submit to having their prints taken so the whole body of prisoners would stand on the same footing. Attorney Moore was denied all access to the prisoners during the consummation of this outrage.

After obtaining permission of the jail officials a committee of Everett citizens, with the voluntary assistance of the Cooks’ and Waiters’ Union, prepared a feast for the free speech prisoners on Thanksgiving Day. When the women arrived at the jail they were met by Sheriff McRae who refused to allow the dinner to be served to the men. McRae was drunk. In place of this dinner the sheriff set forth a meal of moldy mush so strongly doped with chemicals as to be unfit for human consumption. This petty spite work by the moon-struck tool of the lumber trust was in thoro keeping with the cowardly characteristics he displayed on the dock on November 5th. And the extent to which the daily press in Everett was also under the control of the lumber interests was shown by the publication of a faked interview with attorney Fred Moore published in the Everett Herald under date of November 29th, Moore having been credited with the statement that the prison food deserved praise and the prisoners were “given as good food and as much of it as they could wish.”

During the whole of McRae’s term as sheriff

124

there was no time that decent food was given voluntarily to the prisoners as a whole. At times, with low cunning, McRae gave the men in the upper tank better food than those confined below, and also tried to show favoritism to certain prisoners, in order to create distrust and suspicion among the men. All these attempts to break the solidarity of the prisoners failed of their purpose.

On one occasion McRae called “Paddy” Cyphert, one of the prisoners whom he had known as a boy, from his cell and offered to place him in another part of the jail in order that he might escape injury in a “clubbing party” the deputies had planned. Cyphert told McRae to put him back with the rest for he wanted the same treatment as the others and would like to be with them in order to resist the assault. In the face of this determination, which was typical of all the prisoners, the contemplated beating was never administered.

McRae would oftentimes stand outside the tanks at a safe distance and drunkenly curse the prisoners and refer to them as cowards, to which the men would reply by repeating the words of the sheriff on the dock, “O-oh, I’m hit! I-I’m h-hit!! I-I-I’m h-h-hit!!!” Then they would burst forth with a song written by William Whalen in commemoration of the exploits of the doughty sheriff, a song which since has become a favorite of the migratory workers as they travel from job to job, and which will serve to keep the deeds of McRae fresh in the minds of the workers for many years to come.

TO SHERIFF McRAE

Call out your Fire Department, go deputize your bums;

Gather in your gunmen and stool pigeons from the slums;

You may resolute till doomsday, you ill-begotten knave;

We’ll still be winning Free Speech Fights when you are in your grave!

125

You reprobate, you imp of hate, you’re a traitor to the mind

That brought you forth in human shape to prey upon mankind.

You are lower than the snakes that crawl or the scavengers that fly;

You’re the living, walking image of a damn black-hearted lie!

We’ll still be here in Everett when your career is ended,

And back among the dregs of life your dirty hide has blended;

When you shun the path of honest wrath and fear the days to come,

And bow your head to the flag of red, you poor white-livered bum!

For the part you played in Everett’s raid that fateful Sunday morn,

May your kith and kindred live to curse the day that you were born;

May the memory of your victims haunt your conscience night and day,

Until your feeble, insect mind beneath the strain gives way!

Oh, Don McRae, you’ve had your day; make way for Freedom’s host:

For Labor’s sun is rising, soon ’twill shine from coast to coast!

The shot you fired at Everett re-echoes thru the night

As a message to the working class to organize and fight!

Those graves upon the hillside as monuments will stand

To point the way to Freedom’s goal to slaves thruout the land;

And when at last the working class have made the masters yield,

May your portion of the victory be a grave in the Potter’s Field!

126

The end of the first week in January brought about the change in the administrative force of Snohomish county that had been voted at the November election. A new set of lumber trust lackeys were placed in office. James McCullogh succeeded Donald McRae as sheriff, and Lloyd Black occupied the office vacated by Prosecuting Attorney O. T. Webb.

The advent of a new sheriff made some slight difference in the jail conditions, but this was more than offset by the underhanded methods used from that time on with the idea of breaking the solidarity of the free speech fighters. Liquor was placed in the bathrooms where the men could easily get hold of it, but even among those who had been hard drinkers on the outside there were none who would touch it. Firearms were cunningly left exposed in hopes that the men might take them and attempt a jail break, thus giving the jailers a chance to shoot them down or else causing the whole case to be discredited. The men saw thru the ruse and passed by the firearms without touching them.

Working in conjunction with the prosecuting attorney was H. D. Cooley. This gentleman was one of the deputies on the dock, having displayed there his manly qualities by hiding behind a pile of wood at first, and later by telling others to go with rifles to head off the Calista which he had spied approaching from the direction of Mukilteo. Cooley had a practice among the big lumbermen, and in the case against the I. W. W. he was hired by the state with no stipulation as to pay. The general excuse given for his activities in the case, which dated from November 6th, was that he was retained by “friends of Jefferson Beard” and other “interested parties.”

Attorney A. L. Veitch was also lined up with the prosecution. He was the same gentleman who had lectured to the deputies during the preceding fall as a representative of the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Association, and had told the deputies how to handle “outside agitators.” Veitch was also

127

employed by the state as a matter of record, but there was a direct stipulation that he receive no pay from state funds. He also was employed by “friends of Jefferson Beard” and other “interested parties.”

With Veitch there was imported from Los Angeles one Malcolm McLaren, an M. and M. detective and office partner with Veitch, to act as “fix-it” man for the lumber trust. McLaren was at one time an operative for the infamous Wm. J. Burns, and Burns has well said “Private detectives, ninety per cent of them, as a class, are the worst of crooks, blackmailers and scoundrels.” Under McCullogh’s regime this open-shop gumshoe artist had free access to the jail with instructions to go as far as he liked.

Just what the prisoners thought about jail conditions during the time they were incarcerated is given in the following report which was smuggled out to the Industrial Worker and published on March 3rd:

“‘Everything is fine and dandy on the outside, don’t worry, boys.'”

“This is the first thing we heard from visitors ever since we seventy-four have been incarcerated in the Snohomish County Jail at Everett.

“While ‘everything is fine and dandy on the outside’ there are, no doubt, hundreds who would like to hear how things are on the inside. Let us assure everyone on the outside that ‘everything is fine and dandy’ on the inside. We are not worrying as it is but a short time till the beginning of the trials, the outcome of which we are certain will be one of the greatest victories Labor has ever known, if there exists a shadow of justice in the courts of America.

“One hundred days in jail so far—and for nothing! Stop and think what one hundred days in jail means to seventy-four men! It means that in the aggregate the Master Class have deprived us of more than twenty years of liberty. Twenty years! Think of it, and a prospect of twenty more before all are at liberty.

“And why?

128

“There can be but one reason, one answer: We are spending this time in jail and will go thru the mockery of a trial because the masters of Everett are trying to shield themselves from the atrocious murders of Bloody November Fifth.

“After being held in Seattle, convicted without a trial, except such as was given us by the press carrying the advertising of the boss and dependent on him for support, on November 10th forty-one of us were brought to Everett. A few days later thirty more were brought here.

“We found the jail conditions barbarous. There were no mattresses and only one blanket to keep off the chill of a Puget Sound night in the cold, unheated steel cells. There were no towels. We were supplied with laundry soap for toilet purposes, when we could get even that. Workers confined in lower cells were forced to sleep on the floors. There were five of them in each cell and in order to keep any semblance of heat in their bodies they had to sleep all huddled together in all their clothing.

“The first few days we were in the jail we spent in cleaning it, as it was reeking with filth and probably had never been cleaned out since it was built. It was alive with vermin. There were armies of bedbugs and body lice. We boiled up everything in the jail and it is safe to say that it is now cleaner than it had ever been before, or ever will be after the Wobblies are gone.

“When we first came here the lower floor was covered with barrels, boxes and cases of whiskey and beer. This was moved in a few days, but evidently not so far but McRae and his deputies had access to it, as their breath was always charged with the odor of whiskey. It was an everyday occurrence to have several of the deputies, emboldened by liquid courage and our defenseless condition—walk around the cell blocks and indulge in the pastime of calling us vulgar and profane names. Threats were also very common, but we held our peace and were content with the thought that ‘a barking dog seldom bites.’

129

“The worst of these deputies are gone since the advent of sheriff McCullogh, but there are some on the job yet who like their ‘tea.’ About two weeks ago every deputy that came into the jail was drunk; some of them to the extent of staggering.

“When we first entered the jail, true to the principles of the I. W. W., we proceeded to organize ourselves for the betterment of our condition. A ‘grub’ committee, a sanitary committee and a floor committee were appointed. Certain rules and regulations were adopted. By the end of the week, instead of a growling, fighting crowd of men, such as one would expect to find where seventy-four men were thrown together, there was an orderly bunch of real I. W. W.’s, who got up at a certain hour every morning, and all of whose actions were part of a prearranged routine. Even tho every man of the seventy-four was talking as loudly as he could a few seconds before ten p. m., the instant the town clock struck ten all was hushed. If a sentence was unfinished, it remained unfinished until the following day.

“When the jailer came to the door, instead of seventy-four men crowding up and all trying to talk at once, three men stepped forward and conversed with him. Our conduct was astonishing to the jail officials. One of the jailers remarked that he had certainly been given a wrong impression of the I. W. W. by McRae. He said, ‘this bunch is sure different from what I heard they were. You fellows are all right.’ The answer was simply: ‘Organization.’ Instead of a cursing, swearing, fighting mob of seventy-four men, such as sheriff McRae would like to have had us, we were entirely the opposite.

“Time has not hung heavy on our hands. One scarcely notices the length of the days. Educational meetings are frequent and discussions are constantly in order. Our imprisonment has been a matter of experience. We will all be better able to talk Industrial Unionism than when we entered the jail.

“The meals! Did we say ‘meals?’ A thousand

130

pardons! Next time we meet a meal we will apologize to it. Up to the time we asserted our displeasure at the stinking, indigestible messes thrown up to us by a drunken brute who could not qualify as head waiter in a ‘nickel plate’ restaurant, we had garbage, pure and simple. Think of it! Mush, bread and coffee at 7:30 a. m., and not another bite until 4 p. m. Then they handed us a mess which some of us called ‘slumgullion,’ composed of diseased beef. Is it any wonder that four of the boys were taken to the hospital? But we will not dwell on the grub. Suffice it to say we were all more or less sick from the junk dished out to us. We were all hungry from November 10th until January 22nd. One day in November we had beans. Little did we surmise the pains, the agony contained in that dish of innocent looking nutriment, beans. At two in the morning every man in the jail was taken violently ill. We aroused the guards and they sent for a doctor. He came about eight hours later and looked disappointed upon learning that we were not dead. This doctor always had the same remedy in all cases. His prescription was, ‘Stop smoking and you will be all right.’ This is the same quack who helped beat up the forty-one members of the I. W. W. at Beverly Park on October 30th, 1916. His nerve must have failed him or his pills would have finished what his pickhandle had started.

“During the entire time of our confinement under McRae, drunken deputies came into the jail and did everything in their power to make conditions as miserable as possible for us. McRae was usually the leader in villification of the I. W. W.

“When on January 8th a change of administration took place, we called a meeting which resulted in an interview with Sheriff McCullogh. Among other things we demanded a cook. For days the sheriff stalled us off. He professed that he wanted to do things for our comfort. We gave him ample time—but there was no change in the conditions. On January 15th the matter came to a climax. For five

131

days prior to this we had been served with what some called ‘mulligan.’ In reality it was nothing more or less than water slightly colored with the juice of carrots. If there had ever been any meat in it that meat was taken out before the mulligan was served. We called for the sheriff and were informed that he had gone away. We called for one of our attorneys who was in one of the outer offices at the time, but Jailer Bridges refused to let us see him. Having tried peaceful methods without success, we decided to forcibly bring the matter to the attention of the authorities. We poured the contents of the container out thru the bars and onto the floor. The boys in the upper tank did the same thing. For doing this we were given a terrible cursing by Jailer Bridges and the drunken cook, the latter throwing a piece of iron thru the bars, striking one of the boys on the head, and inflicting a long, ugly wound. The cook also threatened to poison us.

“That night when we were to be locked in, one of our jailers, decidedly under the influence of liquor, was in such a condition that he was unable to handle the levers properly and in some manner put the locking system out of commission. After probably three quarters of an hour, during which all of us and every I. W. W. in the world were consigned to hell many times, the doors were finally locked.

“‘By God, you s—s-of-b——s will wish you ate that stew,’ was the way in which the jailer said ‘good night’ to us. The significance of his words was brought back to us next morning when the time came for us to be unlocked. We were left in our cells without food and with the water turned off so we could not even have a drink. We might have remained there for hours without toilet facilities had we not taken matters into our hands. With one accord we decided to get out of the cells. There was only one way to do this—’battleship!’

132

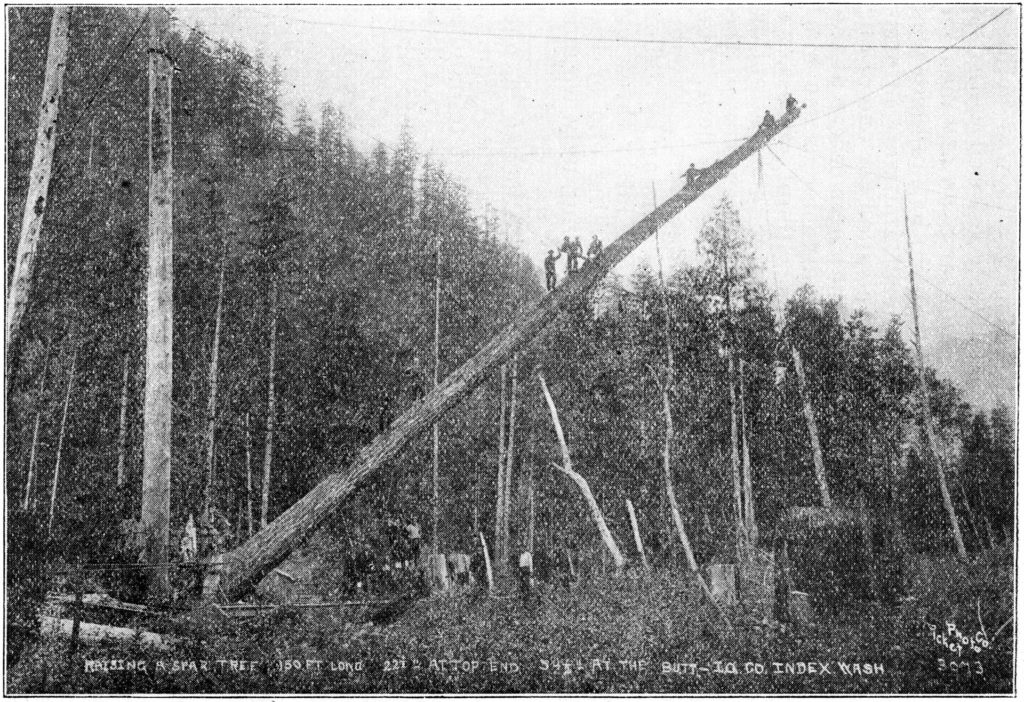

An all-I. W. W. crew raising a spar tree 160 ft. long, 22½

inches at top and 54½ inches at butt, at Index, Wash.

133

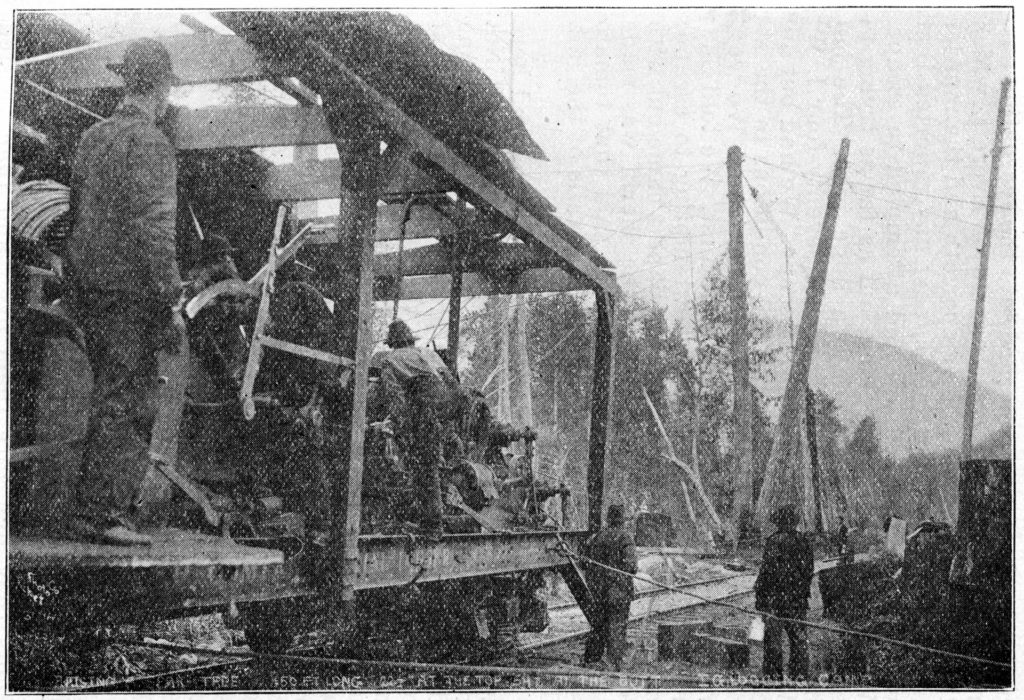

Another view of the same operation.

“Battleship we did! Such a din had never before been heard in Everett. Strong hands and shoulders were placed to the doors which gave up

134

their hold on the locks as if they had been made of pasteboard, and we emerged into the recreation corridors. The lumber trust papers of Everett, which thought the events of November 5th and the murder of five workers but a picnic, next day reported that we had wrecked the jail and attempted to escape. We did do a little wrecking, but as far as trying to escape is concerned that is a huge joke. The jail has not been built that can hold seventy-four I. W. W. members if they want to escape. We had but decided to forcibly bring the jail conditions to the attention of the authorities and the citizens. We were not willing to die of hunger and thirst. We told Sheriff McCullogh we were not attempting to escape; he knew we were not. Yet the papers came out with an alleged interview in which the sheriff was made to say that we were. It was also said that tomato skins had been thrown against the walls of the jail. There were none to throw!

“Summing up this matter: we are here, and here we are determined to remain until we are freed. Not a man in this jail would accept his liberty if the doors were opened. This is proven by the fact that one man voluntarily came to the jail here and gave himself up, while still another was allowed his liberty but sent for the Everett authorities to come and get him while he was in Seattle. This last man was taken out of jail illegally while still under the charge of first degree murder, but he preferred to stand trial rather than to be made a party to schemes of framing up to perjure away the liberties of his fellow workers.

“Signed by the workers in the Snohomish County Jail.”

If the authorities hoped to save money by their niggardly feeding policy the battleship of January 19th, mentioned in the foregoing account, convinced them of their error. With blankets tied to the cell doors they first tore them open and then twisted them out of shape. Taking a small piece of gaspipe they disarranged the little doors that controlled the

135

locking system above each cell, and then demolished the entire system of locks. Every bolt, screw and split pin was taken out and made useless. While some were thus engaged others were busy getting the food supplies which were stacked up in a corner just outside the tanks. When Sheriff McCullogh finally arrived at the jail, some three hours later, he found the prisoners calmly seated amid the wreckage eating some three hundred pounds of corned beef they had obtained and cooked with live steam in one of the bath tubs. Shaking his head sadly the sheriff remarked, “You fellows don’t go to the same church that I do.” The deputy force worked for hours in cleaning up the jail, and it took a gang of ironworkers nine working days, at a cost of over $800.00, to repair the damage done in twenty minutes. Twenty of the “hard-boiled Wobblies” were removed to Seattle shortly after this, but it was no trouble for the men to gain their demands from that time on. They had but to whisper the magic word “battleship” to remind the jailers that the I. W. W. policy, as expressed in a line in Virgil, was about to be invoked:

“If I cannot bend the powers above,

I will rouse Hell.”

Lloyd Black, prosecuting attorney only by a political accident, soon dropped his ideals and filled the position of prosecutor as well as his limited abilities allowed, and it was apparent that he felt the hands of the lumber trust tugging on the strings attached to his job and that he had succumbed to the insidious influence of his associates. He called various prisoners from their cells and by pleading, cajoling and threatening in turn, tried to induce them to make statements injurious to their case.

Fraudulently using the name of John M. Foss, a former member of the General Executive Board of the I. W. W. and then actively engaged in working for the defense, Black called out Axel Downey, a boy of seventeen and the youngest of the free speech prisoners, and used all the resources of his

136

department to get the lad to make a statement. Downey refused to talk to any of the prosecution lawyers or detectives and demanded that he be returned to his cell. From that time on he refused to answer any calls from the office unless the jail committee was present. Nevertheless the name of Axel Downey was endorsed, with several others, as a witness for the prosecution in order to create distrust and suspicion among the prisoners.

About this time the efforts of Detective McLaren and his associates were successful in “influencing” one of the prisoners, and Charles Auspos, alias Charles Austin, agreed to become a state’s witness. Contrary to the expectation of the prosecution, the announcement of this “confession” created no sensation and was not taken seriously on the outside, while the prisoners, knowing there was nothing to confess, were concerned only in the fact that there had been a break in their solidarity. “We wanted to come out of this case one hundred per cent clean,” was the sorrowful way in which they took the news.

Auspos had joined the I. W. W. in Rugby, North Dakota, on August 10th, 1916, and whether he was at that time an agent for the employers is not known, but it is evident that he was not sufficiently interested in industrial unionism to study its rudimentary principles. It may be that the previous record of Auspos had given an opportunity for McLaren to work upon that weak character, for Auspos started his boyhood life in Hudson, Wisconsin, with a term in the reformatory, and his checkered career included two years in a military guard house for carrying side-arms and fighting in a gambling den, a dishonorable discharge from the United States Army, under the assumed name of Ed. Gibson, and various arrests up until he joined the I. W. W.

This Auspos was about 33 years of age, five foot eleven inches tall, weight about 175 pounds, brown hair, brown eyes, medium complexion but face inclined to be reddish, slight scar on side of face, and

137

was a teamster and general laborer by occupation, his parents living in Elk River, Minn.

And while Auspos had by his actions descended to the lowest depths of shame, there were those among the prisoners who had scaled the heights of self-sacrifice. There were some few among them whose record would look none too well in the light of day, but the spirit of class solidarity within them led them to say, “Do with me as you will, I shall never betray the working class.” James Whiteford, arrested under the name of James Kelly, deserves the highest praise that can be given for he was taken back to Pennsylvania, which state he had left in violation of a parole; to serve out a long penitentiary sentence which he could have avoided by a few easily told lies implicating his fellow workers in a conspiracy to do murder on November 5th.

Shortly after the attempted “frame-up” with Axel Downey there was a strong effort made to bring pressure upon Harvey Hubler. A “lawyer” who called himself Minor Blythe, bearing letters obtained by misrepresentation from Hubler‘s father and sister, attempted to get Hubler from his cell on an order signed by Malcolm McLaren, the detective. With the experience of Downey fresh in mind, Hubler refused to go out of the tank, even tho the “lawyer” stated that he had been sent by Hubler‘s father and could surely get him out of jail.

The next day twelve armed deputies came into the jail to force Hubler to accompany them to the office. The prisoners as a whole refused to enter their cells, and armed themselves with such rude weapons as they could find in order to repulse the deputies. The concerted resistance had its effect and a committee of three, Feinberg, Peters and Watson, accompanied Hubler to the office. Hubler there refused to read the letter, asking that it be read aloud in the presence of the other men. The detectives refused to do this and the men were put back in the tank.

That afternoon, with two other prisoners,

138

Hubler went out of the tank to wash his clothes. The jailers had been awaiting this opportunity and immediately locked the men out. The gunmen then overpowered Hubler and dragged him struggling to the office. The letter was then read to Hubler, who made no comment further than to say that the I. W. W. had engaged attorneys to defend him and he wished to be taken back where the rest of the men were.

Meanwhile the men in the tanks had started another battleship. A hose had been installed in the jail since the previous battleship and the deputies turned this upon the men as soon as the protest started. The prisoners retaliated by taking all mattresses, blankets, clothing and supplies belonging to the county and throwing them where they would be ruined by the water, and not knowing what was happening to Hubler they shouted “Murder” at the top of their voices. While the trouble was going on several members of the I. W. W., many Everett citizens, and one attorney tried to gain admittance to the jail office to learn the cause of the disturbance, but this was denied for more than an hour. Hubler was finally brought back and the battleship ceased. The county had to furnish new bedding and clothing for the prisoners.

After this occurrence the prisoners were allowed the run of the corridors and were often let out to play ball upon the jail lawn, with only two guards to watch them. There were no disorders in the jail from that time on.

A committee of Everett women asked permission to serve a dinner to the imprisoned men and when this was granted they fairly outdid themselves in fixing up what the boys termed a “swell feed.” This was served to the men thru the bars but tasted none the less good on that account.

139

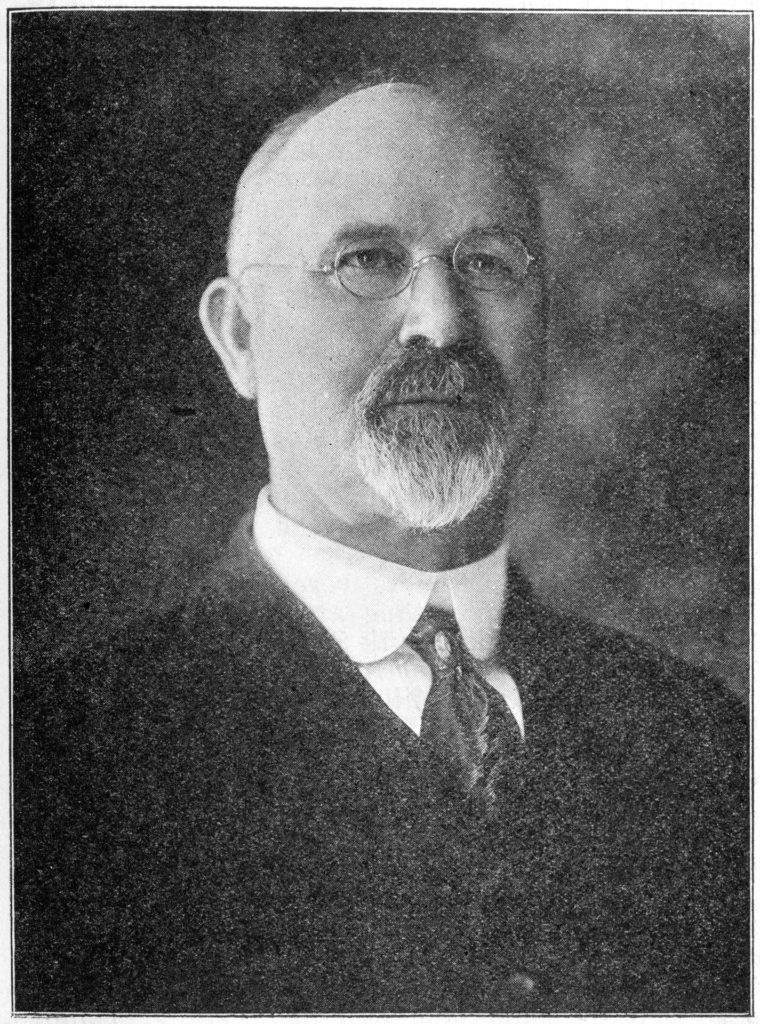

Judge J. T. Ronald

The Seattle women, not to be outdone, gave a banquet to the prisoners who had been transported to the Seattle county jail. The banquet was spread on tables set the full length of the jail corridor, and

140

the menu ran from soup to nuts. An after dinner cigar, and a little boutonniere of fragrant flowers furnished by a gray-haired old lady, completed the program.

These banquets and the jail visitors, together with numerous books, magazines and papers—and a phonograph that was in almost constant operation—made the latter part of the long jail days endurable.

The defense was making strong efforts, during this time, to secure some judge other than Bell or Alston, the two superior court judges of Snohomish County, finally winning a victory in forcing the appointment of an outside judge by the governor of the state.

Judge J. T. Ronald, of King County, was selected by Governor Lister, and after the men had pleaded “Not Guilty” on January 26th, a change of venue on account of the prejudice existing in Everett’s official circles was asked and granted, Seattle being selected as the place where the trial would take place.

Eleven of the prisoners were named on the first information, the men thus arraigned being F. O. Watson, John Black, Frank Stuart, Charles Adams, Harston Peters, Thomas H. Tracy, Harry Feinberg, John Downs, Harold Miller, Ed Roth and Thomas Tracy. The title of the case was “State vs. F. O. Watson et al.,” but the first man to come to trial was Thomas H. Tracy. The date of the trial was set for March 5th.

On November 5th, when he was taken from the Verona to jail, Thomas H. Tracy gave his name at the booking window as George Martin, in order to spare the feelings of relatives to whom the news of his arrest would have proven a severe shock. When the officers were checking the names later he was surprised to hear them call out “Tracy, Thomas Tracy.” Thinking that his identity was known because of his having been secretary in Everett for a time, he stepped forward. An instant later a little fellow half his size also marched to the front. There

141

were two Tom Tracys among the arrested men! Neither of them knew the other! Tracy then gave his correct name and both he and “Little Tom Tracy” were later held among the seventy-four charged with murder in the first degree.

During all the time the free speech fighters were awaiting trial the lumber trust exerted its potent influence at the national capital to the end of preventing any congressional investigation of the tragedy of November 5th and the circumstances surrounding it. The petitions of thousands of citizens of the state of Washington were ignored. All too well the employers knew what a putrid state of affairs would be uncovered were the lumber trust methods exposed to the pitiless light of publicity. That the trial itself would force them into the open evidently did not enter into their calculations.

In changing the information charging the murder of C. O. Curtis to the charge of murdering Jefferson Beard the prosecution thought to cover one point beyond the possibility of discovery, which change seems to have been made as a result of the exhuming of the body of C. O. Curtis in February. Curtis had been buried in a block of solid concrete and this had to be broken apart in order to remove the body. Just who performed the autopsy cannot be ascertained as the work was covered in the very comprehensive bill of $50.50 for “Exhuming the body of C. O. Curtis, and autopsy thereon,” this bill being made out in the name of the superintendent of the graveyard and was allowed and paid by Snohomish County. This, together with the fact that at no time during the trial did the prosecution speak of C. O. Curtis as having met his death at the hands of the men on the Verona, seems to bear out the contention of the defense that Curtis was the victim of the rifle fire of one of his associates.

So on March 5th, after holding the free speech prisoners for four months to the day, the lumber trust, in the name of the State of Washington, brought the first of them, Thomas H. Tracy, to trial, on a charge of first degree murder, in the King County Court House at Seattle, Washington.