9

The Everett Massacre

CHAPTER I.

THE LUMBER KINGDOM

Perhaps the real history of the rise of the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest will never be written. It will not be set down in these pages. A fragment—vividly illustrative of the whole, yet only a fragment—is all that is reproduced herein. But if that true history be written, it will tell no tales of "self-made men" who toiled in the woods and mills amid poverty and privation and finally rose to fame and affluence by their own unaided effort. No Abraham Lincoln will be there to brighten its tarnished pages. The story is a more sordid one and it has to do with the theft of public lands; with the bribery and corruption of public officials; with the destruction and "sabotage," if the term may be so misused, of the property of competitors; with base treachery and double-dealing among associated employers; and with extortion and coercion of the actual workers in the lumber industry by any and every means from the "robbersary" company stores to the commission of deliberate murder.

No sooner had the larger battles among the lumber barons ended in the birth of the lumber trust than there arose a still greater contest for control of the industry. Lumberjack engaged lumber baron in a

10

struggle for industrial supremacy; on the part of the former a semi-blind groping toward the light of freedom and for the latter a conscious striving to retain a seat of privilege. Nor can the full history of that struggle be written here, for the end is not yet, but no one who has read the past rightly can doubt the ultimate outcome. That history, when finally written, will recite tales of heroism and deeds of daring and unassuming acts of bravery on the part of obscure toilers beside which the vaunted prowess of famous men will seem tawdry by comparison. Today the perspective is lacking. Time alone will vindicate the rebellious workers in their fight for freedom. From all this travail and pain is to be born an Industrial Democracy.

The lumber industry dominated the whole life of the Northwest. The lumber trust had absolute sway in entire sections of the country and held the balance of power in many other places. It controlled Governors, Legislatures and Courts; directed Mayors and City Councils; completely owned Sheriffs and Deputies; and thru threats of foreclosure, blackmail, the blacklist and the use of armed force it dominated the press and pulpit and terrorized many other elements in each community. The sworn testimony in the greatest case in labor history bears out these statements. Out of their own mouths were the lumber barons and their tools condemned. For, let it be known, the great trial in Seattle, Wash., in the year 1917, was not a trial of Thomas H. Tracy and his co-defendants. It was a trial of the lumber trust, a trial of so-called “law and order,” a trial of the existing method of production and exchange and the social relations that spring from it,—and the verdict was that Capitalism is guilty of Murder in the First Degree.

To get even a glimpse into the deeper meaning of the case that developed from the conflict at Everett, Wash., it is necessary to know something of the lives of the migratory workers, something of the vital necessity of free speech to the working class

11

and to all society for that matter, and also something about the basis of the lumber industry and the foundation of the city of Everett. The first two items very completely reveal themselves thru the medium of the testimony given by the witnesses for the defense, while the other matters are covered briefly here.

The plundering of public lands was a part of the policy of the lumber trust. Large holdings were gathered together thru colonization schemes, whereby tracts of 160 acres were homesteaded by individuals with money furnished by the lumber operators. Often this meant the mere loaning of the individual’s name, and in many instances the building of a home was nothing more than the nailing together of three planks. Other rich timber lands were taken up as mineral claims altho no trace of valuable ore existed within their confines. All this timber fell into the hands of the lumber trust. In addition to this there were large companies who logged for years on forty acre strips. This theft of timber on either side of a small holding is the basis of many a fortune and the possessors of this stolen wealth can be distinguished today by their extra loud cries for “law and order” when their employes in the woods and mills go on strike to add a few more pennies a day to their beggarly pittance.

Altho cheaper than outright purchase from actual settlers, these methods of timber theft proved themselves quite costly and the public outcry they occasioned was not to the liking of the lumber barons. To facilitate the work of the lumber trust and at the same time placate the public, nothing better than the Forest Reserve could possibly have been devised. The establishment of the National Forest Reserves was one of the long steps taken in the United States in monopolizing both the land and the timber of the country.

The first forest reserves were established February 22, 1898, when 22,000,000 acres were set aside as National Forests. Within the next eight

12

years practically all the public forest lands in the United States that were of any considerable extent had been set off into these reserves, and by 1913 there had been over 291,000 square miles included within their confines.[1] This immense tract of country was withdrawn from the possibility of homestead entry at approximately the time that the Mississippi Valley and the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains had been settled and brought under private ownership. Whether the purpose was to put the small sawmills out of business can not be definitely stated, but the lumber trust has profited largely from the establishment of the forest reserves.

So long as there was in the United States a large and open frontier to be had for the taking there could be no very prolonged struggle against an owning class. It has been easier for those having nothing to go but a little further and acquire property for themselves. But on coming to what had been the frontier and finding a forest reserve with range riders and guards on its boundaries to prevent trespassing; on looking back and seeing all land and opportunities taken; on turning again to the forest reserve and finding a foreman of the lumber trust within its borders offering wages in lieu of a home, it was inevitable that a conflict should occur.

With the capitalistic system of industry in operation, the conflict between the landless homeseekers and the owners of the vast accumulations of capital would inevitably have taken place, but this clash has come at least a generation earlier because of the establishment of the National Forests than it otherwise would. The land now in reserves would furnish homes and comfortable livings for ten million people, and have absorbed the surplus population for another generation. It is also true that the establishment of the National Forests has been one of the

13

vital factors that made the continued existence of the lumber trust possible.

Prior to 1895 the shipments of lumber to the prairie states from west of the Rocky Mountains were very small, and of no effect on the domination of the lumber industry by the trust. Also, prior to that date but a small part of the valuable timber west of the Rocky Mountains had been brought under private ownership. But about this time the pioneer settlers began swarming over the Pacific Slope and taking the free government land as homesteads. As the timber land was taken up, floods of lumber from the Pacific Coast met the lumber of the trust on the great prairies. The lumber trust had looted the government land and the Indian reservations in the middle states of their timber, and had almost full control of the prairie markets until the lumber of the Pacific Slope began to arrive. In 1896 lumber from the Puget Sound was sold in Dakota for $16.00 per thousand feet, and it kept coming in a constantly increasing volume and of a better quality than the trust was shipping from the East. It was but natural that the trust should seek a means to stifle the constantly increasing competition from the homesteads of the West, and the means was found in the establishment of the National Forest Reserves.

While the greater portion of North America was yet a wilderness, the giving of vast tracts of valuable land on the remote frontier to private individuals and companies could be accomplished. But at this time such a procedure would have been impossible, tho it was imperative for the life of the trust that the timber of the Pacific Slope should be withdrawn from the possibility of homestead entry. In order to carry out this scheme it was necessary to raise a cry of "Benefit to the Public" and make it appear that this new public policy was in the interest of future generations. The cry was raised that the public domain was being used for private gain, that the timber was being wastefully handled, that unnecessary amounts were being cut, that the future generations would find themselves without timber

14

that the watersheds were being denuded and that drought and floods would be the certain result, that the nation should receive a return for the timber that was taken, together with many other specious pleas.

That the public domain was being used for private gain was in some instances true, but the vast majority of the timber land was being taken as homesteads, and thus taking the timber outside the control of the trust. That the timber was being wastefully handled was to some extent true, but this was inevitable in the development of a new industry in a new country, and so far as the Pacific Slope is concerned there is but little change from the methods of twenty years ago. That unnecessary amounts were being cut was sometimes true, but this served only to keep prices down, and from the standpoint of the trust was unpardonable on that account alone. The market is being supplied now as formerly, and with as much as it will take. The only means that has been used to restrict the amount cut has been to raise the price to about double what it was in 1896. The denuding of the watersheds of the continent goes on today the same as it did twenty-five years ago, the only consideration being whether there is a market for the timber. Some reforesting has been done, and some protection has been established for the prevention of fires, but these things have been much in the nature of an advertisement since the government has taken charge of the forests, and was done automatically by the homesteaders before the Reserves were established. There has never been any restriction in the amount of timber that any company could buy, and the more it wanted, the better chance it had of getting it. The nation is receiving some return from the sale of timber from the government land, but it is in the nature of a division of the spoils from a raid on the homes of the landless.

When the Reserve were established, the Secretary of the Interior was empowered to "make rules and regulations for the occupancy and the use of the forests and preserve them from destruction." No

15

attempt was made in the General Land Office to develop a technical forestry service. The purpose of the administration was mainly protection against trespass and fire. The methods of the administration were to see to it first that there were no trespassers. Fire protection came later. When the Reserves were established, people who were at the time living within their boundaries were compelled to submit the titles of their homesteads to the most rigid scrutiny, and many people who had complied with the spirit of the law were dispossessed on mere technicalities, while before the establishment of the Reserve system the spirit of the compliance with the homestead law was mainly considered, and very seldom the technicality. And while the Forestry Service was examining all titles to homesteads within the boundaries of the Reserve with the utmost care, the large lumbering companies were given the best of consideration, and were allowed all the timber they requested and a practically unlimited time to remove it.

The system of dealing with the lumber trust has been most liberal on the part of the government. A company wanting several million feet of timber makes a request to the district office to have the timber of a certain amount and on a certain tract offered for sale. The Forestry Service makes an estimate of the minimum value of the timber as it stands in the tree and the amount of timber requested within that tract is then offered for sale at a given time, the bids to be sent in by mail and accompanied by certified checks. The bids must be at least as large as the minimum price set by the Forestry Service, and highest bidder is awarded the timber, on condition that he satisfies the Forestry Service that he is responsible and will conduct the logging according to rules and regulations. The system seems fair, and open to all, until the conditions are known.

But among the large lumber companies there has never been any real competition for the possession of any certain tract of timber that was listed for sale by request. When one company has decided on

16

asking for the allotment of any certain tract of timber, other companies operating within that forest seldom make bids on that tract. Any small company that is doing business in opposition to the trust companies, and may desire to bid on an advertised tract, even tho its bid may be greater than the bid of the trust company, will find its offer thrown out as being "not according to the Government specifications," or the company is "not financially responsible," or some other suave explanation for refusing to award the tract to the competing company. On the other hand, when a small company requests that some certain tract shall be listed for sale, it very frequently happens that one of the large companies that is commonly understood to be affiliated with the lumber trust will have a bid in for that tract that is slightly above that of the non-trust company, and the timber is solemnly awarded to "the highest bidder."

When a company is awarded a tract of timber, the payment that is required is ten per cent of the purchase price at the time of making the award, and the balance is to be paid when the logs are on the landing, or practically when they can be turned into ready cash, thus requiring but a comparatively small outlay of money to obtain the timber. When the award is made, it is the policy of the Forestry Service to be on friendly terms with the customers, and the men who scale the logs and supervise the cutting are the ones who come into direct contact with the companies, and it is inevitable that to be on good terms with the foreman the supervision and scaling must be "satisfactory." Forestry Service men who have not been congenial with the foremen of the logging companies have been transferred to other places, and it is almost axiomatic that three transfers is the same as a discharge. The little work that is required of the companies in preventing fires is much more than offset by the fact that no homesteaders have small holdings within the area of their operations, either to interfere with logging or to compete with their small mills for the control of the lumber market.

17

That the forest lands of the nation were being denuded, and that this would cause droughts and floods was a fact before the establishment of the Reserves, and the fact is still true. Where a logging company operates, the rule is that it shall take all the timber on the tract where it works, and then the forest guards are to burn the brush and refuse. A cleaner sweep of the timber could not have been made under the old methods. The only difference in methods is that where the forest guards now do the fire protecting for the lumber trust, the homesteaders formerly did it for their own protection. In January, 1914, the Forestry Service issued a statement that the policy of the Service for the Kaniksu Forest in Northern Idaho and Northeastern Washington would be to have all that particular reserve logged off and then have the land thrown open to settlement as homesteads. As the timber in that part of the country will but little more than pay for the work of clearing the land ready for the plow, but is very profitable where no clearing is required, it can be readily seen that the Forestry Service was being used as a means of dividing the fruit—the apples to the lumber trust, the cores to the landless homeseekers.

One particular manner in which the Government protects the large lumber companies is in the insurance against fire loss. When a tract has been awarded to a bidder it is understood that he shall have all the timber allotted to him, and that he shall stand no loss by fire. Should a tract of timber be burned before it can be logged, the government allots to the bidder another tract of timber "of equal value and of equal accessibility," or an adjustment is made according to the ease of logging and value of the timber. In this way the company has no expense for insurance to bear, which even now with the fire protection that is given by the Forestry Service is rated by insurance companies at about ten per cent. of the value of the timber for each year.

No taxes or interest are required on the timber

18

that is purchased from the government. Another feature that makes this timber cheaper than that of private holdings, is that to buy outright would entail the expense of the first cost of the land and timber, the protection from fire, the taxes and the interest on the investment. In addition to this there is always the possibility that some homesteader would refuse to sell some valuable tract that was in a vital situation, as holding the key to a large tract of timber that had no other outlet than across that tract. There has been as yet no dispute with the government about an outlet for any timber purchased on the Reserves; the contract for the timber always including the proviso that the logging company shall have the right to make and use such roads as are "necessary," and the company is the judge of what is necessary in that line.

The counties in which Reserves are situated receive no taxes from the government timber, or from the timber that is cut from the Reserves until it is cut into lumber, but in lieu of this they receive a sop in the form of "aid" in the construction of roads. In the aggregate this aid looks large, but when compared with the amount of road work that the people who could make their homes within what is now the Forest Reserves could do, it is pitifully small and very much in the nature of the "charity" that is handed out to the poor of the cities. It is the inevitable result of a system of government that finds itself compelled to keep watch and ward over its imbecile children.

So in devious ways of fraud, graft, coercion, and outright theft, the bulk of the timber of the Northwest has been acquired by the lumber trust at an average cost of less than twelve cents a thousand feet. In the states of Washington and Oregon alone, the Northern Pacific and the Southern Pacific railways, as allies of the Weyerhouser interests of St. Paul, own nearly nine million acres of timber; the Weyerhouser group by itself dominating altogether more than thirty million acres, or an area almost

19

equal to that of the state of Wisconsin. The timber owned by a relatively small group of individuals is sufficient to yield enough lumber to build a six-room house for every one of the twenty million families in the United States.

Why then should conservation, or the threat of it, disturb the serenity of the lumber trust? If the government permits the cutting of public timber it increases the value of the trust holdings in multiplied ratio, and if the government withdraws from public entry any portion of the public lands, creating Forest Reserves, it adds marvelously to the value of the trust logs in the water booms. Even forest fires in one portion of these vast holdings serve but to send skyward the values in the remaining parts, and by some strange freak of nature the timber of trust competitors, like the "independent" and co-operative mills, seems to be more inflammable than that of the "law-abiding" lumber trust. And so it happens that the government's forest policy has added fabulous wealth and prestige and power to the rulers of the lumber kingdom.

But whether the timber lands were stolen illegally or acquired by methods entirely within the law of the land, the exploitation of labor was, and is, none the less severe. The withholding from Labor of any portion of its product in the form of profits—unpaid wages—and the private ownership by individuals or small groups of persons, of timber lands and other forms of property necessary to society as a whole, are principles utterly indefensible by any argument save that of force. Such legally ordained robbery can be upheld only by armies, navies, militia, sheriffs and deputies, police and detectives, private gunmen, and illegal mobs formed of, or created by, the propertied classes. Alike in the stolen timber, the legally acquired timber, and in the Government Forest Reserves, the propertyless lumberjacks are unmercifully exploited, and any difference in the degree of exploitation does not arise because of the "humanity" of any certain set

20

of employers but simply because the cutting of timber in large quantities brings about a greater productivity from each worker, generally accompanied with a decrease in wages due to the displacement of men.

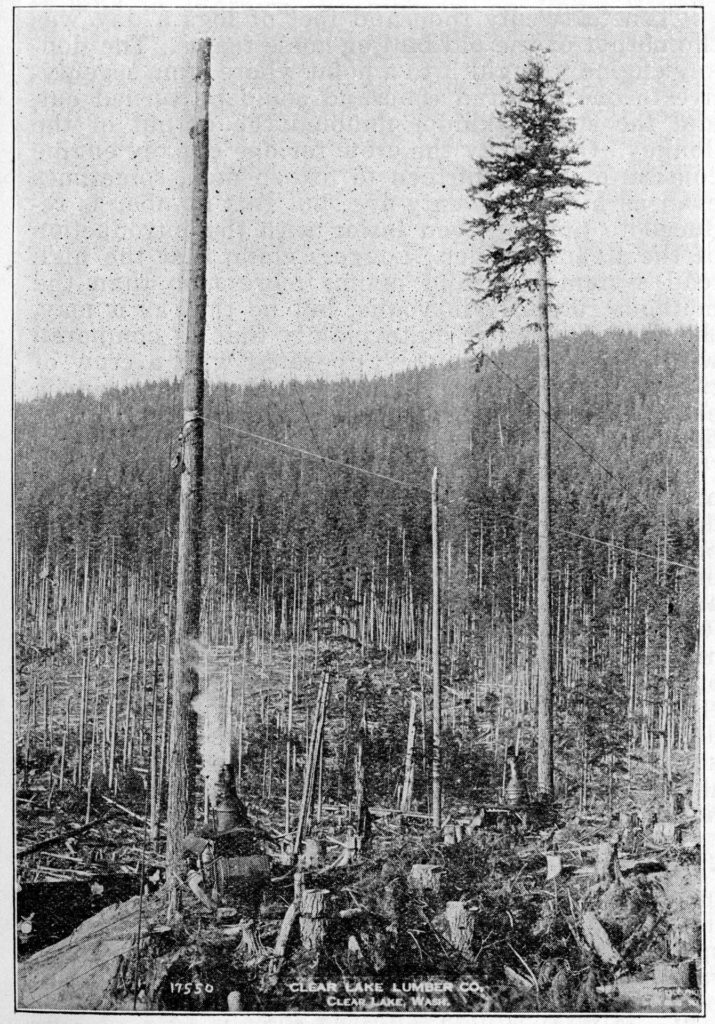

With the development of large scale logging operations there naturally came a development of machinery in the industry. The use of water power, the horse, and sometimes the ox, gave way to the use of the donkey engine. This grew from a crude affair, resembling an over-sized coffee mill, to a machine with a hauling power equal to that of a small sized locomotive. Later on came "high lead" logging and the Flying Machine, besides which the wonderful exploits of "Paul Bunyan's old blue ox" are as nothing.

The overhead system was created as a result of the additional cost of hauling when the increased demand for a larger output of logs forced the erection of more and more camps, each new camp being further removed from the cities and towns. Today its use is almost universal as there remains no timber close to the large cities, even the stumps having been removed to make room for farming operations.

Roughly the method of operation is to leave a straight tall tree standing near the logging track in felling timber. The machine proper is set right at the base of this tree, and about ninety feet up its trunk a large chain is wrapped to allow the hanging of a block. From this spar tree a cable, two inches in diameter, is stretched to another tree some distance in the woods. On this cable is placed what is known as a bicycle or trolley. Various other lines run back and forth thru this trolley to the engine. At the end of one of these lines an enormous pair of hooks is suspended. These grasp the timber and convey it to the cars.

21

The Flying Machine as now used in Western logging.

22

Ten to twenty thousand feet of logs a day was the output of the old bull or horse teams. The donkey engine brought it to a point where from seventy-five to one hundred thousand could be turned out, and the steam skidder doubled the output of the donkey. Ordinarily the crew for one donkey engine consists of from thirteen to fifteen men, sometimes even as high as twenty-five, but this number is reduced to nine or even lower with the introduction of the steam skidder. Loggers claim that the high lead system kills and maims more men than the methods formerly in vogue, but be that as it may, the fact stands out quite plainly that as compared with a line horse donkey, operated with a crew of twenty-five men, the flying machine will produce enough lumber to mean the displacement of one hundred men.

At the same time the sawmills of the old type have disappeared with their rotary or circular saws, dead rollers, and obsolete methods of handling lumber, and in their place is the modern mill with its band saw, shot-gun feed, steam nigger, live rollers, and resaw. Nor do the mills longer turn out rough lumber to be re-handled by trained specialists and highly skilled carpenters with large and costly kits of intricate hand tools. Relatively unskilled workers send forth the finished products, window sashes, doors, siding, etc., carpenters armed only with square, hammer and saw, and classed with unskilled labor, put these in place, and a complete house can be ordered by parcel post.

As is usual with the introduction of new machinery and methods where the workers are not in control, the actual producers find that all these innovations force them to work at a higher rate of speed under more hazardous conditions for a lower rate of pay. It is true of all industry in the main, particularly true of the lumber industry, and the mills of Everett and camps of Snohomish county have no exceptions to test this rule.

The story of Everett has no hint of romance. Some time in the late seventies the representatives

23

of John D. Rockefeller gained possession of a tract of land in Western Washington, on Puget Sound, about thirty miles north of Seattle. The land was heavily timbered and water facilities made it a perfect site for mill and shipping purposes. The Everett Land Company was organized, the tract was plotted, and the city of Everett laid out. The leading streets, Rockefeller, Colby, Hoyt, etc., were named for these early promoters. Hewitt Avenue was given the name of a man who is today recognized as the leading capitalist of the state of Washington. Even the building of those streets reflected no credit upon the city. The work was done by what amounted to convict labor. Unemployed workers, even tho they were plentifully supplied with money, were arrested and without being allowed the alternative of a fine were set to work clearing, grading, planking and, later on, paving the streets. Perhaps it is too much to expect freedom of speech to be allowed on slave-built streets.

In their articles of incorporation the promoters reserved to themselves all right to the ownership and control of public utilities, such as water, light and power and street railway systems. A mortgage of $1,500,000 was placed upon the property. After a time the company failed, the mortgage was foreclosed and the property purchased by Rucker Brothers. The Everett Improvement Company was then organized with J. T. McChesney as president. It held all rights to dispose of public utility franchises. The firm of Stone & Webster, the construction, light, heat, power and traction trust, secured franchises granting them the right to furnish light and power for the city of Everett and also to operate the street railway system for 99 years. The Everett Improvement Company owns a dock lying to the south of the municipally owned City Dock where the Everett tragedy was staged. Thru its alliances the shipping of Everett is in the hands of the same group of capitalists that control all other public utilities. The waterworks was sold to the city but has remained in the hands of the same officials who were in charge

24

when its title was a private one. Everett operates under the commission form of government.

The American National Bank was organized with McChesney as president. The only other bank of importance in Everett was the First National. These two institutions consolidated with Wm. C. Butler as president and McChesney as one of the directors. The Everett Savings and Trust Company was later organized, with the same stockholders and under the same management as the First National Bank. The control of every public service corporation in Everett is directly in the hands of these two banks, and, indirectly, thru loans to industrial corporations, they control both the lumber and the shingle mills of Snohomish County in which Everett is situated.

Everett, the "City of Smokestacks," as its promoters have named it, is an industrial community of approximately 35,000 people. Its main activities are the production of lumber and shingles, and shipping. The practically undiversified nature of its economic life binds all those engaged in the employment of labor into a common body. The owners of the lumber and shingle mills, the owners and officials of the banks where the lumber men do business, the lawyers representing the mills and the banks, the employers engaged in shipping lumber and supplies for the lumber industry, their lawyers and their bank connections, the owners of hardware stores that supply equipment for the mills and allied industries, all are united by common ties and common interests and they all support one policy. Not only are they banded together against the wage workers but they also oppose the entrance of any kind of business that will in any way menace their rule. They arose almost as one in opposition to the entrance of the ship building industry into Everett, despite the fact that it would add measurably to the general prosperity of the city, and with a full knowledge that their harbor offered wonderful natural facilities for that line of endeavor. In the face of

25

an action that threatened their autocratic power their alleged "patriotism" vanished.

In 1912 the Everett Commercial Club was organized. In the month of December, 1915, following a visit from a San Francisco representative of the Merchants and Manufacturers' Association, it was re-organized on the Bureau plan as a stock concern. Stock memberships were issued to employers and business houses and were subsequently distributed among the employers and their employes. Memberships were doled out to persons who would be subservient to the wishes of the small group of capitalists representing the great corporate interests. W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club, testified, under oath, that the Everett Improvement Company took 25 memberships, the First National Bank took 10, the Weyerhouser Lumber Company 10, the Clough-Hartley Mill Company 5, the Jamison Mill Company 5, and other mills and allied industries also purchased memberships in bulk. Organized labor, however, had no representation at the Commercial Club.

There is nothing in the history of Everett to suggest the usual spontaneous outgrowth of the honest endeavors of hardy pioneer settlers. From the first day the Rockefeller interests set foot in the virgin forests of Snohomish County up to the present time, the spirit of democracy has been crushed by the greed and cupidity of this small and powerful group.

The struggle at Everett was but one of the inevitable phases of the larger struggle that takes place when a class or group that has no property comes in contact with those who have monopolized the earth and its resources. It was no new, marvelous, isolated case of violence. It was the normal accompaniment of industry based upon the exploitation of wage workers, and was of one piece with the outbreak on the Mesaba Range, in Bayonne, Ludlow, Paint Creek, Paterson, Lawrence, San Diego, Fresno, Spokane, Homestead and in countless other places. All these apparently

26

disconnected and sporadic uprisings of labor and the accompanying capitalist violence are joined together in a whole that spells wage slavery. As one of the manifestations of the class conflict, the Everett tragedy cannot be considered apart from that age-long and world-wide struggle between the takers of profits and the makers of values.

FOOTNOTE:

[1] Data on Forest Reserve taken from 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica articles by Gifford Pinchot.