142

CHAPTER VI.

THE PROSECUTION

The King County Court House is an imposing, five story, white structure, covering an entire block in the business section of the city of Seattle. Its offices for the conduct of the county and city business are spacious and well appointed. Its corridors are ample, and marble. The elevator service is of the best. But the courtrooms are stuffy little dens, illy ventilated, awkwardly placed, and with the poorest of acoustics. They seem especially designed to add to the depressing effect that invariably attends the administration of “law and order.” The court of Judge Ronald, like many other courts in the land, is admirably designed for the bungling inefficiencies of “justice.” Yet it was in this theater, thru the medium of the Everett trial, that the class struggle was reproduced, sometimes in tragedy and sometimes in comedy.

To reach the greatest trial in the history of labor unionism, perhaps the greatest also in the number of defendants involved and the number of witnesses called, one had to ascend to the fourth floor of the court house and line up in the corridor under the watchful eyes of the I. W. W. “police,” C. R. Griffin and J. J. Keenan, appointed by the organization at the request of the court. There, unless one were a lawyer or a newspaper representative, it was necessary to wait in line for hours until the tiny courtroom was opened and the lucky hundred odd persons were admitted to the church-like benches of J. T. Ronald’s sanctum, where the case of State versus Tracy was on trial.

Directly in front of the benches, at the specially constructed press table, were seats provided for the representatives of daily, weekly and monthly

143

publications whose policies ranged from the ultra conservative to the extreme radical. Here the various reporters were seen writing madly as some important point came up, then subsiding into temporary indifference, passing notes, joking in whispers, drawing personal cartoons of the judge, jury, counsel, court functionaries and out-of-the-ordinary spectators,—the only officially recognized persons in the courtroom showing no signs of reverence for the legal priesthood and their mystic sacerdotalism.

Just ahead of the press table were the attorneys for the prosecution: Lloyd Black, a commonplace, uninspired, beardless youth as chief prosecutor; H. D. Cooley, a sleek, pusillanimous recipient of favors from the lumber barons, a fixture at the Commercial Club, and an also-ran deputy at the dock on November 5th, as next counsel in line; and A. L. Veitch, handsome in a gross sort of a way, full faced, sensual lipped, with heavy pouches beneath the eyes, a self-satisfied favorite of the M. & M., and withal the most able of the three who by virtue of polite fiction represented the state of Washington. From time to time in whispered conference with these worthy gentlemen was a tall, lean, grey, furtive-eyed individual who was none other than the redoubtable Californian detective, Malcolm McLaren.

At right angles to this array of prosecutors the counsel for the defense were seated, where they remained until the positions were reversed at the close of the prosecution’s case. Chief counsel Fred H. Moore, serious, yet with a winning smile occasionally chasing itself across his face and adding many humorous wrinkles to the tired-looking crow-feet at the corners of his eyes; next to him George F. Vanderveer, a strong personality whose lightning flashes of wit and sarcasm, marshalled to the aid of a merciless drive of questions, were augmented by a smile second only to Moore’s in its captivating quality; then E. C. Dailey, invaluable because of his knowledge of local conditions in Everett and personages connected with the case; and by his side, at

144

times during the trial, was H. Sigmund, special counsel for Harry Feinberg.

Seated a little back, but in the same group, was a man of medium height, stocky built, slightly ruddy complexion, black hair, and twinkling blue eyes. He was to all appearances the most composed man in the courtroom. A slight smile crept over his face, at times almost broadened into a laugh, and then died away. This was Thomas H. Tracy, on trial for murder in the first degree.

To the rear of the defendant and forming a deep contrast to the determined, square-jawed prisoner was the guard, a lean, hungry-looking deputy with high cheek bones, unusually sharp and long nose and a pair of moustachios that drooped down upon his chest, a wholly useless and most uncomfortable functionary who could scarce seat himself because of the heavy artillery scattered over his anatomy.

The court clerk, an absurdly dignified court bailiff, a special stenographer, and Sheriff McCullogh of Snohomish county, occupied the intervening space to the pulpit from which Judge J. T. Ronald delivered his legal invocations.

The judge, a striking figure, over six feet in height and well proportioned, of rather friendly countenance and bearing in street dress, resembled nothing so much as a huge black owl when arrayed in his sacred “Mother Hubbard” gown, with tortoise-shell rimmed smoked glasses resting on his slightly aquiline nose and surmounting the heavy, closely trimmed, dark Vandyke beard.

To the right of the judge as he faced the audience was the witness chair, and across the whole of the corner of the room was a plat of the Everett City Dock and the adjacent waterfront, together with a smaller map showing part of the streets of the city. The plat was state’s exhibit “A.” Below these maps on a tilted platform was a model of the same dock, with the two warehouses, waiting room, Klatawa Slip, and the steamer Verona, all built to scale. This was defendant’s exhibit “1.”

Extending from these exhibits down the side of

145

the railed enclosure, were seats for two extra jurors. The filling of this jury box from a long list of talesmen was the preliminary move to a trial in which the defendant was barely mentioned, and which involved the question of Labor’s right to organize, to assemble peaceably, to speak freely, and to advocate a change in existing social arrangements. Capital was lined up in a fight against Labor. There was a direct reflection in the courts of the masters of the age-long, world-wide class struggle.

The examination of talesmen occupied considerable time. Each individual was asked whether he had read any of the following papers: The Industrial Worker, The Socialist World, or the Pacific Coast Longshoreman. The prosecution also inquired as to the prospective juror’s familiarity with the I. W. W. Song Book and the various works on Sabotage. Union affiliations were closely inquired into, and favorable mention of the right to organize brought a challenge from the state. The testing of the talesmen was no less severe on the part of the defense.

Fifty-one talesmen were disqualified, after long and severe legal battles, before a jury was finally secured from among the voters and property owners who alone were qualified to serve. The jury, as selected, was rather more intelligent than was to be expected when consideration is taken of the fact that any person who acknowledged having an impression, an opinion, or a conclusion regarding the merits of the case was automatically excused from service. Those who were chosen to sit on the case were:

Mrs. Mattie Fordran, wife of a steamfitter; Robert Harris, a rancher; Fred Corbs, bricklayer, once a member of the union, then working for himself; Mrs. Louise Raynor, wife of a master mariner; A. Peplan, farmer; Mrs. Clara Uhlman, wife of a harnessmaker in business for himself; Mrs. Alice Freeborn, widow of a druggist; F. M. Christian, tent and awning maker; Mrs. Sarah F. Brown, widow, working class family; James R. Williams, machinist’s

146

helper, member of union; Mrs. Sarah J. Timmer, wife of a union lineman, and T. J. Byrne, contractor. The two alternate jurors, provided for under the “Extra Juror” law of Washington, passed just prior to this trial, were: J. W. Efaw, furniture manufacturer, president of Seattle Library Board and Henry B. Williams, carpenter and member of a union.

Judge Ronald realized the importance of the case as was shown in his admonition to the jury, a portion of which follows:

“It is plain, from both sides here, that we are making history. Let us see that the record that we make in this case,—you and I, as a court,—be a landmark based upon nothing in the world but the truth. We may deceive some people and we may, a little, deceive ourselves; but we cannot deceive eternal truth.”

On the morning of March 9th Judge Ronald, the tail of his black gown firmly in hand, swept into the courtroom from his private chambers, the assembled congregation arose and stood in deep obeisance before His Majesty The Law, the pompous bailiff rapped for order and delivered an incantation, the Judge seated himself on the throne of “Justice,” the assemblage subsided into their seats—and the trial was opened in earnest. Prosecuting Attorney Lloyd Black then gave his opening statement, the gist of which is contained in the following quotations:

“You are at the outset of a murder trial, murder in the first degree. The defendant, Thomas H. Tracy, alias George Martin, is charged with murder in the first degree, in having assisted, counselled, aided, abetted and encouraged some unknown person to kill Jefferson Beard on the 5th of November, 1916.

“* * * As far as the state is concerned, no one knows or can know or could follow the course of the particular bullet that struck and mortally wounded and killed Jefferson Beard.

“* * * The evidence further will show that the first, or one of the first, shots fired was from

147

the steamer Verona and was from a revolver held in the hand of Thomas H. Tracy.

“* * * As to the killing of Jefferson Beard itself the probabilities are, as the evidence of the state will indicate, that he was killed by someone on the hurricane deck of the Verona because the evidence will show that the revolver shots went thru his overcoat, missing his coat, and thru his vest, and had a downward course, so that it must have come from the upper deck. The evidence will show that Thomas H. Tracy was on the main deck firing thru an open cabin window.

“* * * Of the approximately 140 special and regular deputies of Snohomish County about one-half were armed, some with revolvers, some with rifles and some with clubs.

“* * * When the fusilade had come from the I. W. W.’s on the Verona, a portion of the deputies ran thru a door into this warehouse, (indicating): a portion of them went into that warehouse, and used some of the knotholes there, and some shot holes thru which they could see, * * *”

Black then gave a recital of the lumber trust version of the events leading up to November 5th, bringing in the threats of an alleged committee who were said to have declared “that they would call thousands of their members to the city of Everett, flood the jails, demand separate trials, and tie up and overwhelm the court machinery, and that the mayor should consider that they had beaten Spokane and killed its chief, killed Chief Sullivan of that city, that they had defeated Wenatchee and North Yakima, and now it was Everett’s turn.”

“* * * That in furtherance of their threats that they would burn the city of Everett, that a number of mysterious fires took place, fires connected with some person who was opposed to the I. W. W. * * * And in addition, the I. W. W. members were arrested at different times preceding this trouble on the 5th of November and phosphorus was found upon their person either in cans or wrapped up.

148

“* * * At different times, the evidence will show, Sheriff Donald McRae and other peace officers of the city of Everett, including Mayor Merrill, received anonymous letters, and also received direct statements from the I. W. W. that they would get them; and, as one speaker put it, he says ‘Sheriff McRae will wake up some day and say ‘”Good morning, Jesus!”’

Black continued his recital of events, admitting the “Wanderer” incident, but he tried to sidestep the criminal actions at Beverly Park.

“Now, there happened at Beverly Park an incident that the State in this action doesn’t feel that it has anything to do with this particular cause.”

Ironical laughter at this juncture caused the removal of several spectators from the courtroom. So disconcerted was Black that he proceeded to give away the real cause of action against the I. W. W.

“The I. W. W. organization itself is an unlawful conspiracy, an unlawful conspiracy in that it was designed for the purpose of effecting an absolute revolution in society and in government, effecting it not by the procedure of law thru the ballot, but for effecting it by direct action. The I. W. W. meant to accomplish the change in society, not by organization as the labor unions hope to get higher wages, not to get into effect their theory of society by the ballot, as the Socialists hope, but that they expressly state that the election of a Socialist president will accomplish no good, and that sabotage should be employed against government ownership as well as against private production, so that directly they might put into effect their theories of government and society.”

The defense reserved the right to make their opening statement at the close of the prosecution’s case, thus leaving the state in the dark as to the line of defense, and forcing them to open their case at once.

Lester L. Beard and Chester L. Beard, twin sons of the deceased deputy sheriff, testified as to the condition of their father’s clothing, Attorney

149

Vanderveer drawing from Lester Beard the admission that his father was an employment agent in Seattle in 1914.

Following them, Drs. William O’Keef Cox, H. P. Howard, and William P. West testified to having performed an autopsy on Beard and described the course of the bullet upon entering the body. Dr. West was an armed guard at the land end of the City Dock on November 5th, Dr. Cox was also on the dock as a deputy, and Dr. Howard carried a membership in the Commercial Club. They were the physicians present when the autopsy was performed.

The next witness, Harry W. Shaw, a wood and coal dealer of Everett, admitted having joined the citizen deputies because of a call issued by the sheriff thru the Commercial Club. Shaw went to the dock on November 5th, carrying, as he claimed, a revolver with a broken firing pin which he had hoped to have repaired on that Sunday on the way to the dock. He was close to Beard when the latter fell and helped to carry him from the open space on the dock into the warehouse. He afterward accompanied Beard to the hospital in an automobile and returned to the dock with Beard’s unfired revolver in his possession. He swore that he had seen McRae sober three times in succession! When asked by Attorney Moore he gave an affirmative answer to this pertinent question:

“You knew that the matter of the enforcement of the city ordinances of Everett was peculiarly within the powers of the police department of the city, didn’t you?”

Owen Clay was then called to the stand. Clay had been made bookkeeper of the Weyerhouser Mill about a year and a half before this, and had been given a membership in the Commercial Club at the time. He was injured in the right arm in the trouble at the dock and then ran around the corner of the ticket office, after which he emptied his

150

revolver with his left hand. Attorney Vanderveer questioned this witness as follows:

“Who shot Jeff Beard in the right breast?”

“I don’t know.”

“Did you do it?”

“I don’t know.”

“Thank you! That’s all,” said Vanderveer with a smile.

The next witness was C. A. Mitchell, employee of the Clark-Nickerson Mill. He testified that he belonged to Company “B” under the command of Carl Clapp. His testimony placed Sheriff McRae in the same position as that given by the preceding witness, about eight to ten feet from the face of the dock in the center of the open space between the two warehouses, but unlike Clay, who testified that McRae had his left hand in the air, he was positive that the sheriff had his right hand in the air at the time the shooting started.

W. R. Booth, engaged in real estate and insurance business, a member of the Commercial Club, and a deputy at the dock, was next called. Attorney Cooley asked this witness about the speech made at an unspecified street meeting. Vanderveer immediately objected as follows:

“We object to that as immaterial and calling for a conclusion of the witness. He does not know who was speaking, nor whether he was authorized to do it, or brought there by the Industrial Workers of the World, or a hireling of the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ society. It has happened time and time again that people are employed by these capitalists themselves to go out and make incendiary speeches and cause trouble, and employed to go out and fire buildings and do anything to put the opposition in wrong.”

When questioned about McRae’s position on the dock, Booth stated that the sheriff had both hands in the air. This witness admitted having been a member of the “Flying Squadron” and being a participant in the outrage at Beverly Park. He named others who went out with him in the same

151

automobile, Will Seivers and Harry Ramwell, and stated that A. P. Bardson, clerk of the Commercial Club, was probably there as he had been out on all the other occasions. He said that he would not participate in the beating up of anyone, and that when the affair started he went up the road for purposes of his own. He was asked by Vanderveer as to the reason for continuing to associate with people who had abused the men at Beverly Park, to which he replied:

“Because I believe in at least trying to maintain law and order in our city.”

During the examination of this witness, and at various times thruout the long case, it was only with evident effort that Attorney Vanderveer kept on the unfamiliar ground of the class struggle, his natural tendencies being to try the case as a defense of a pure and simple murder charge.

W. P. Bell, an Everett attorney representing a number of scab mills, a member of the Commercial Club and a deputy on the dock, testified next, contradicting the previous witnesses but throwing no additional light upon the case. He was followed by Charles Tucker, a scab and gunman employed by the Hartley Shingle Company and a deputy on the dock. Tucker lied so outrageously that even the prosecution counsel felt ashamed of him. He was impeached by his own testimony.

Editor J. A. MacDonald of the Industrial Worker was called to the stand to show the official relation of the paper to the I. W. W. and to lay a foundation for the introduction of a file of the issues prior to November 5th. A portion of the file was introduced as evidence and at the same time the state put in as exhibits a copy of the I. W. W. Constitution and By-Laws, Sabotage by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Sabotage by Walker C. Smith, The Revolutionary I. W. W. by Grover H. Perry, The I. W. W., Its History, Structure and Methods by Vincent St. John, and the Joe Hill Memorial Edition of the Song Book.

152

Herbert Mahler, former secretary of the Seattle I. W. W. and at the time Secretary-Treasurer of the Everett Prisoners’ Defense Committee, was next upon the stand. He was asked to name various committees and to identify certain telegrams. The unhesitatingly clear answers of both MacDonald and Mahler were in vivid contrast to the mumbled and contradictory responses of the deputies.

William J. Smith, manager of the Western Union Telegraph Company was then called to further corroborate certain telegrams sent and received by the I. W. W.

As the next step in the case prosecutor Black read portions of the pamphlet “Sabotage” by Smith, sometimes using half a paragraph and skipping half, sometimes using one paragraph and omitting the next, provoking a remonstrance from Attorney Vanderveer which was upheld by the Court in these words:

“You have a right to do what you are doing, Mr. Black, but it don’t appeal to my sense of fairness if other omissions are as bad as the one you left out. You are following the practice, but I don’t know of an instance where there has been such an awful juggling about, and it is discretionary with the Court, and I want to be fair in this case. I want to let them have a chance to take the sting out of it so as to let the jury have both sides, because it is there. Now, Mr. Vanderveer, I am going to leave it to you not to impose upon the Court’s discretion. Any new phases I don’t think you have the right to raise, but anything that will modify what he has read I think you have the right to.”

Thereupon Vanderveer read all the omitted portions bearing upon the case, bringing special emphasis on these two parts:

“Note this important point, however. Sabotage does not seek nor desire to take human life.”

“Sabotage places human life—and especially the life of the only useful class—higher than all else in the universe.”

153

With evidences of amusement, if not always approval, the jury then listened to the reading of numerous I. W. W. songs by Attorney Cooley for the prosecution, tho some of the jurymen shared in the bewilderment of the audience as to the connection between the song “Overalls and Snuff” and defendant Tracy charged with a conspiracy to commit murder in the first degree.

D. D. Merrill, Mayor of Everett, next took the stand. He endeavored to give the impression that the I. W. W. was responsible for a fire loss in Everett of $100,000.00 during the latter part of the year 1916. Vanderveer shot the question:

“From whom would you naturally look for information on the subject of fires?”

“From the Fire Chief, W. C. Carroll,” replied the mayor;

“We offer this report in evidence,” said Vanderveer crisply.

The report of the Fire Chief was admitted and read. It showed that there were less fires in 1916 that in any previous year in the history of Everett, and only four of incendiary origin in the entire list!

The prosecution tried to squirm out of this ticklish position by stating that they meant also the fires in the vicinity of Everett, but here also they met with failure for the principal fire in the surrounding district was in the co-operative mill, owned by a number of semi-radical workingmen at Mukilteo.

The mayor told of having been present at the arrest of several men taken from a freight train at Lowell, just at the Everett city limits. Some of these men were I. W. W.’s, and on the ground afterward there was said to have been found some broken glass about which there was a smell of phosphorus. The judge ruled out this evidence because there were other than I. W. W. men present, no phosphorus was found on the men, and if only one package were found it would not indicate a conspiracy but might have been brought by an agent

154

of the employers. This was the nearest the prosecution came at any time in the trial in their attempt to connect the I. W. W. with incendiary fires.

A tense moment in this sensational trial came during the testimony of Mayor Merrill, when young Louis Skaroff was suddenly produced in court and the question flashed at the cringing witness:

“Do you recognize this boy standing here? Do you recognize him, Louis Skaroff?”

“I think I have seen him,” mumbled the mayor.

“Let me ask you if on the 6th day of November at about ten o’clock at night in a room in the City Hall at Everett where there was a bed room having an iron bedstead in it, in the presence of the jailer, didn’t you have an interview with this man?”

Merrill denied having mutilated Skaroff’s fingers beneath the casters of the bed, but even the capitalist press reported that his livid face and thick voice belied his words of denial.

And Prosecutor Lloyd Black remarked heatedly, “I don’t see the materiality of all this.”

Merrill left the stand, having presented the sorriest figure among the number of poor witnesses produced by the prosecution.

Carl Clapp, superintendent of the Municipal Waterworks at Everett, and commander of one of the squads of deputies, followed with testimony to the effect that sixty rifles from the Naval Militia were stored in the Commercial Club on November 5th. At this juncture the hearing of further evidence was postponed for a half day to allow Attorney Vanderveer to testify on behalf of Mayor H. C. Gill in a case then pending in the Federal Court.

On several other occasions Vanderveer was called to testify in this case and there were times when it was thought that he also would be indicted and brought to trial, yet with this extra work and the threat of imprisonment hanging over him, Vanderveer never flagged in his keen attention to the work of the defense. It was commonly thought that the case against Gill and the attempt to involve

155

Vanderveer were moves of the lumber trust and Chamber of Commerce directed toward the I. W. W., for in the background were the same interested parties who had been forced to abandon the recall against Seattle’s mayor. Gill’s final acquittal in this case was hailed as an I. W. W. victory.

Upon the resumption of the trial the prosecution temporarily withdrew Clapp and placed Clyde Gibbons on the stand. This witness was the son of James Gibbons, a deceased member of the I. W. W., well and favorable known in the Northwest. James Gibbons was killed by a speeding automobile about a year prior to the trial, and his widow and son, Clyde, were supported by the I. W. W. and the Boiler Makers’ Union for several months thereafter.

Clyde Gibbons, altho but seventeen years old, joined the Navy by falsifying his age. Charity demands that the veil be drawn over the early days of Clyde’s training, yet his strong imagination and general untruthfulness are matters of record. He was shown in court to have stolen funds left in trust with him by Mrs. Peters, one of the persons against whom his testimony was directed. It is quite probable that the deceit about his age, or some other of his queer actions, were discovered and used to force him to testify as the prosecution desired. The following testimony bears out this idea:

“Who was it that you met at the Naval Recruiting Station and took you to McLaren?”

“I don’t know his name.”

“Well, how did you get to talking to this total stranger about the Everett matter?”

“He told me he wanted to see me in the judge’s office.”

“And they took you down to the judge’s office, did they?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And when you got to the judge’s office you found you were in Mr. McLaren’s and Mr. Veitch’s and Mr. Black’s office in the Smith Building?”

“Yes, sir.”

156

Gibbons testified as to certain alleged conversations in an apartment house frequented by members of the I. W. W., stating that a party of members laid plans to go to Everett and to take with them red pepper, olive oil and bandages. Harston Peters, one of the defendants, had a gun that wouldn’t shoot and so went unarmed, according to this witness. Gibbons also stated that Mrs. Frenette took part in the conversation in this apartment house on the morning of the tragedy, whereupon Attorney Moore asked him:

“On directing your attention to it, don’t you remember that you didn’t see Mrs. Frenette at all in Seattle, anywhere, at any time subsequent to Saturday night; that she went to Everett on Saturday night?”

“Well, I am quite sure I saw her Sunday, but maybe I am mistaken.”

The judge upheld the defense attorneys in their numerous objections to the leading questions propounded by prosecutor Black during the examination of this witness.

Clapp was recalled to the stand and testified further that Scott Rainey, head of the U. S. Naval Militia at Everett, had ordered Ensign McLean to take rifles to the dock, and that the witness and McLean had loaded the guns, placed them in an auto and taken them to the dock, where they were distributed to the deputies just as the Verona started to steam away.

Ignorance as to the meaning of simple labor terms that are in the every-day vocabulary of the “blanketstiff” was shown by Clapp in his answers to these queries:

“What is direct action?”

“Using force instead of lawful means.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, either physical force, or conspiracy.”

“You understand conspiracy to be some kind of force, do you?”

“It may be force.”

157

When asked where he had obtained information about sabotage, this witness said that he had looked up the word in Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, a work in which the term is strangely absent.

Clapp was the first witness to admit the armed character of the deputy body and also to state that deputies with guns were stationed on all of Everett’s docks.

After excusing this witness, Cooley brought in copies of two city ordinances covering street speaking in Everett. One of them which allowed the holding of meetings at the corner of Hewitt and Wetmore Avenues was admitted without question, but the other which purported to have been passed on September 19, 1916, was objected to on the ground that it had not been passed, was never put upon passage and never moved for passage in the Everett City Council.

Richard Brennan, chauffeur of the patrol wagon, A. H. Briggs, city dog catcher, and Floyd Wildey, police officer, all of Everett, then testified regarding the arrest of I. W. W. members during August and September. Wildey stated that on the night of August 30 four or five members of the I. W. W. came away from their street meeting carrying sections of gaspipe in their hands. This was thought to be quite a blow against the peaceful character of the meeting until it was discovered on cross-examination that the weapons were the removable legs of the street speaking platform.

David Daniels, Arthur S. Johnson, Garland Queen, J. R. Steik, M. J. Fox and, later on, Earl Shaver, all of whom were police officers in Everett, gave testimony along somewhat the same lines as the other witnesses from Everett who owed their jobs to the lumber trust. They stated that the I. W. W. men deported on August 23rd, had made threats against McRae and several police officers.

Ed. M. Hawes, proprietor of a scab printing and stationery company, member of the Commercial Club and citizen deputy, gave testimony similar

158

to that of other vigilantes as to the trouble on November 5th. When asked if he had ever known any I. W. W. men offering resistance, Hawes replied that one had tried to start a fight with him at Beverly Park. Having thus established his connection with this infamous outrage, further questioning of this witness developed much of the story of the brutal gauntlet and deportation. Hawes told of one of his prisoners making an endeavor to escape, and when asked whether he blamed the man for trying to get away, answered that he thought the prisoner was a pretty big baby.

“You thought he was a pretty big baby?” queried Vanderveer.

“Yes, sir.”

“Or do you think the men were pretty big babies and cowards who were doing the beating?”

The witness had no answer to this question.

“How much do you weigh?” demanded Vanderveer sharply.

“I weigh 260 pounds,” replied Hawes.

Frank Goff and Henry Krieg, two young lads who were severely beaten at Beverly Park, were suddenly produced in court and the big bully was made to stand alongside of them. He outweighed the two of them. It was plainly evident who the pretty big baby was!

Howard Hathaway, law student and assistant to the state secretary of the Democratic Central Committee, was forced to admit his connection with the raid upon the launch “Wanderer” and also upon the men peacefully camping at Maltby. His testimony was mainly for the purpose of making it appear that James P. Thompson had advocated that the shingle weavers set fire to the mills and win their strikes by methods of terrorism.

Two newspaper reporters, William E. Jones of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and J. J. Underwood of the Seattle Times, were placed upon the stand in order to lay the foundation for an introduction of an article appearing in the P-I on Sunday morning,

159

November 5th. Jones testified that he was present at the Seattle police station when Philip K. Ahern, manager of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, requested the release of Smith and Reese, two of his operatives who had been on the Verona. Underwood stated that upon hearing of the treatment given the I. W. W. men at Beverly Park he had exclaimed, “I would like to see anybody do that to me and get away with it.”

“You meant that, did you?” asked Vanderveer.

“You bet I meant it!” asserted the witness positively.

The two reporters proved to be better witnesses for the defense than for the prosecution.

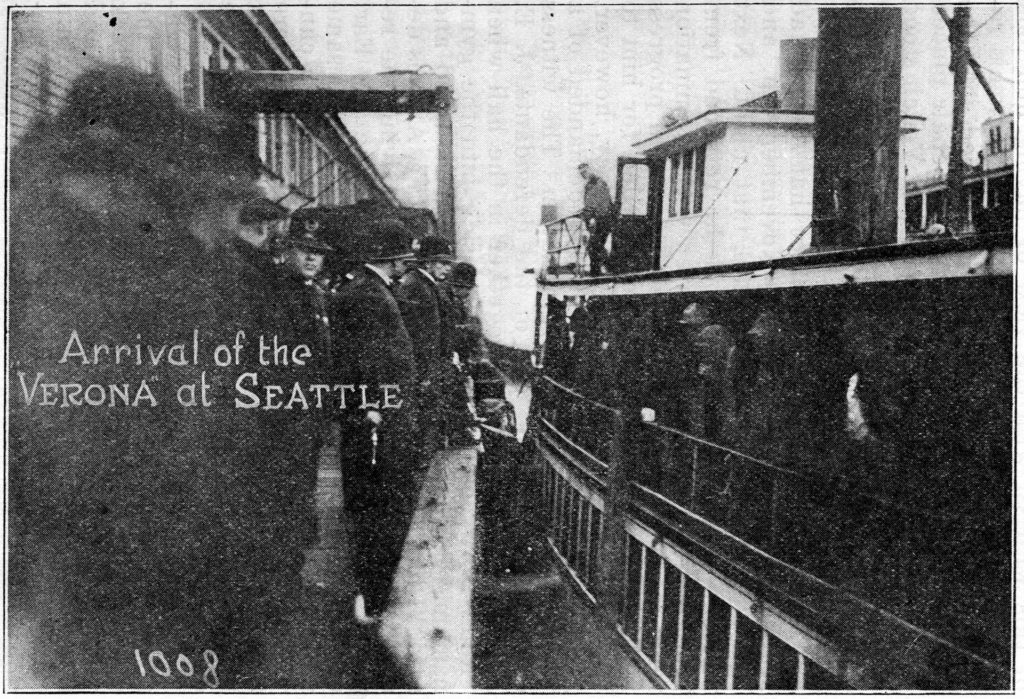

Sanford Asbury, T. N. Henry, Ronald Johnson, John S. Donlan, and J. E. Gleason, then testified regarding the movements of the men who left Seattle on the Verona and Calista on the morning of November 5th. They uniformly agreed that the crowd was in no way disorderly, nor were their actions at all suspicious. The defense admitted that the Verona had been chartered but stated that there were passengers other than I. W. W. members on board.

The first witness from the Verona was Ernest Shellgren, the boat’s engineer, who testified that he was in the engine pit when the boat landed and heard crackling sounds telegraphed down the smoke stack that he knew an instant later were bullets. He was struck by a spent bullet and ran to various places on the boat seeking shelter from the hail of lead that appeared to come from all directions, finally returning to the boiler as the safest place on the boat. He stated that he saw one man firing a blue steel revolver from the boat, only the hand and revolver being in his line of vision. The only other gun he saw was one in the hands of the man who asked him to back the boat away from the dock during the firing. He also stated that the I. W. W. men on the way over to Everett comported themselves as was usual with any body of passengers.

Shellgren was asked if he could identify John

160

Downs or Thomas H. Tracy as being connected with the firing in any way and he stated that he could not do so. The defense objected to the use of Downs’ picture, as it did on every occasion where a picture of one of the prisoners was used, on the grounds that the photographs were obtained by force and in defiance of the constitutional rights of the imprisoned free speech fighters.

Seattle police detectives, Theodore Montgomery and James O’Brien, who made a search of the Verona upon its return to Seattle, testified to having found a little loose red pepper, two stones the size of a goose egg tied up in a cloth, and a few empty cartridges. These two witnesses also developed the fact that in no case were regular bandages used on the wounded men, thus establishing the fact that no serious trouble was anticipated.

James Meagher, occupation “home owner,” member of the Commercial Club and citizen deputy, testified that a hundred shots were fired from the Verona before a gun was pulled on the dock, one of the first shots striking him in the leg. This witness was asked:

“Did you see a single gun on the boat?”

“No sir,” was his mumbled response.

The prosecution witnesses disagreed as to the number of lines of deputies stretched across the back and sides of the open space on the dock, the statements varying from one to four files.

Chad Ballard, Harry Gray, and J. D. Landis, of the Seattle police detective bureau, and J. G. McConnell, Everett Interurban conductor, testified to the return and arrest of Mrs. Frenette, Mrs. Mahler and Mrs. Peters, after the trouble on November 5th. The police officers also told of a further searching of the Verona on its return. The defense admitted that some of the members had red pepper in their possession and stated that they would ask the judge to instruct the jury that red pepper is a weapon of defense and not of offense and that murder cannot be committed with red pepper.

161

Elmer Buehrer, engineer at the Everett High School, and citizen deputy, gave testimony that was halting, confused and relatively unimportant. He was prompted by the prosecution to such an extent that Attorney Vanderveer at the close of one question said, “Look at me and not at counsel.”

“Look where you please,” cried Cooley angrily.

“Well, look where you please,” rejoined Vanderveer. “He can’t help you.”

It was apparent that the only reason for putting on this witness and former witness Meagher was because of a desire to create sympathy thru the fact that they had been wounded on the dock.

Edward Armstrong, master mariner on the Verona, testified that he had thrown out the spring line and lifted out the gate when the firing started. He fell to the deck behind a little jog, against the bulkhead, and while in that position two bullets went thru his cap. Altho this witness stated that he judged from the sound that the first shot came from some place to the rear of him, his testimony as to the attitude of McRae was as follows:

“I seen him with his right hand hanging on the butt of the gun.”

“And that was before there was any shooting?”

“Yes sir.”

As to the condition of the boat after the trouble he gave an affirmative answer to the question:

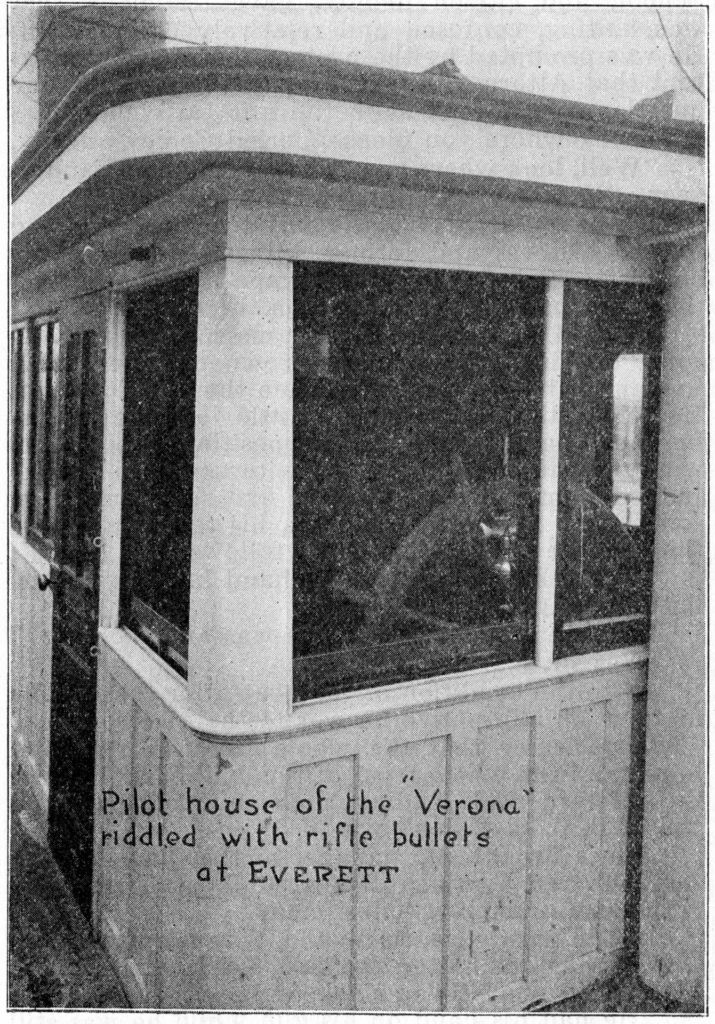

“You know that the whole front of the pilot house and the whole front of this bulkhead front of the forward deck leading to the hurricane deck is full of B. B. shot, don’t you?”

James Broadbent, manager of the Clark-Nickerson Mill, and a citizen deputy, followed Armstrong with some unimportant testimony.

L. S. Davis, steward on the Verona, also stated that McRae committed the first overt act in taking hold of his gun. He was asked:

“He had his hand on his gun while he was still facing you?”

“Yes sir. I could see it plainly,” answered Davis.

162

Pilot house of the "Verona" riddled with rifle bullets at Everett

163

“That was before he started to turn, before he was hit?”

“Yes sir.”

Davis was wounded in the arm as he was on the pilot house steps.

He was asked about the general disposition, manner and appearance of the men on the Verona on the way over to Everett, and answered:

“I thought they were pretty nicely behaved for men—for such a crowd as that.”

“Any rough talk; any rough, ugly looks?”

“No sir.”

“Any guns?”

“No.”

“Any threats?”

“I didn’t hear any threats.”

“Jolly, good-natured bunch of boys?”

“Yes.”

“Lots of young boys among them, weren’t there?”

“Yes, quite a few.”

Davis stated that three passengers got off at Edmunds on the way up to Everett, thus establishing the fact that there were other than I. W. W. men on board.

R. S. “Scott” Rainey, commercial manager of the Puget Sound Telephone Company and a citizen deputy, was called and examined at some length before it was discovered that he was not an endorsed witness. This was the second time that the prosecution had turned this trick. Vanderveer objected, stating that there would be two hundred endorsed witnesses who would not be used.

“Oh no!” returned Mr. Veitch.

“Well,” said Vanderveer, “a hundred then. A hundred we dare you to produce!”

“We will take that dare,” responded Veitch. But the prosecution failed to keep their word, and deputy Dave Oswald of the Pacific Hardware Company, who during the various deportations tried to have the I. W. W. men stripped, covered with hot

164

tar, rolled in feathers and ridden out of town on a rail, and a number of his equally degenerate brother outlaws were never produced in court.

Rainey testified that he had seen a quantity of murderous looking black-jacks in the Commercial Club for distribution to the deputies. He also saw men fall overboard from the Verona and saw none of them rescued. He thought there were twenty-five men with guns on the boat, and he did his firing at the main deck.

“And you didn’t care whether you hit one of the twenty-five or one of the other two hundred and twenty-five?” scornfully inquired Vanderveer.

“No sir,” said the miserable witness.

The next witness called was William Kenneth, city dock wharfinger in the employ of Captain Ramwell. This witness testified that there were numerous holes in the warehouses that were smooth on the inside and splintered on the outside, thus indicating that they were from shots blindly fired thru the walls from within. On being recalled on the Monday morning session of March 26th the witness said he wished to state that he was unable to testify from which direction the holes in the warehouses had been made. It appeared that he had discovered the bullet marks to have been whittled with a penknife since he had last viewed them.

Arthur Blair Gorrell, of Spokane, student at the State University, was on the dock during the trouble and was wounded in the left shoulder blade. He stated that he knew that McRae had his gun drawn before he was shot.

Captain K. L. Forbes, of the scab tugboat Edison, next took the witness chair. He didn’t like the idea of calling his crew scabs for the engineer carried a union card. When questioned about the actions of the scab cook on the Edison, this witness would not state positively that the man was not firing directly across the open space on the dock at the Verona, and in line with Curtis and other deputies.

165

Thomas E. Headlee, ex-mayor of Everett, bookkeeper at the Clark-Nickerson mill, and a citizen deputy, said he went whenever and wherever he was called to go by the sheriff.

“Then it’s just like this,” said Vanderveer, “when you pull the string, up jumps Headlee?”

This witness tried to blame all the fires in Everett onto the I. W. W. and the absurdity of his testimony brought this question from the defense:

“Just on general principles you blame it on the I. W. W.?”

“Sure!” replied the witness, “I got their reputation over in Wenatchee from my brother-in-law who runs a big orchard there.”

Lewis Connor, member of the Commercial Club, and his friend, Edwin Stuchell, university student, both of whom were deputies on the dock on November 5th, then testified, but developed nothing of importance. Stuchell’s father was part owner of the Eclipse mill and was said to have been on the board of directors of the Commercial Club. These witnesses were followed by Raymond E. Brown, owner of an Everett shoe store, a weak-kneed witness who had been sworn in as a deputy by W. W. Blain, secretary of the Commercial Club.

One of the greatest sensations in this sensational trial was when former sheriff Donald McRae took the stand on Tuesday, March 27th.

McRae was sober!

The sheriff was fifty years of age, of medium height, inclined to stoutness, smooth-shaven, with swinish eyes set closely on either side of a pink-tinted, hawk-like nose that curved just above a hard, cruel and excessively large mouth. The sneering speech and contemptible manner of this witness lent weight to the admissions of his brutality that had been dragged from reluctant state’s witnesses thru the clever and cutting cross-examination conducted by Moore and Vanderveer.

McRae told of his former union affiliations, having once been International Secretary of the Shingle

166

Weavers’ Union, and on another occasion the editor of their paper—but he admitted that he had never in his life read a book on political economy.

He detailed the story of the arrests, deportations and other similar actions against the striking shingle weavers and the I. W. W. members, the recital including an account of the “riot” at the jail, the deportation of Feinberg and Roberts, the shooting at the launch “Wanderer” and the jailing of its passengers, and the seizing of forty-one men and their deportation at Beverly Park. McRae’s callous admissions of brutality discounted any favorable impression his testimony might otherwise have conveyed to the jury.

He admitted having ordered the taking of the funds of James Orr to pay the fares of workers deported on August 23rd, but denied the truth of an account in the Everett Herald of that date in which it was said that I. W. W. men had made some remarks to him “whereupon Sheriff McRae and police officer * * promptly retaliated by cracking the I. W. W.’s on the jaw with husky fists.”

Regarding the launch “Wanderer” the sheriff was asked:

“Did you strike Captain Mitten over the head with the butt of your gun?”

“Certainly did!” replied McRae with brutal conciseness.

“Did any blood flow?”

“A little, not much.”

“Not enough to arouse any sympathy in you?”

“No,” said the sheriff unfeelingly.

“Did you strike a little Finnish fellow over the head with a gun?”

“I certainly did!”

“And split his head open and the blood ran out, but not enough to move you to any sympathy?”

“No, not a bit!” viciously answered McRae.

“Did you hit any others?” inquired Vanderveer.

“No, not then.”

“Why not?”

167

“They probably seen what happened to the captain and the other fellow for getting gay.”

As to the holding of Mitten in jail for a number of days on a charge of resisting an officer, and his final release, McRae was asked:

“Why didn’t you try him on that charge?”

“Because when we let the I. W. W.’s go they insisted on him going, too, and I said, ‘all right, take him along.'”

“You did whatever the I. W. W.’s wanted in that?”

“Well, I was glad to get rid of them,” remarked the sheriff.

McRae said that none of the men taken to Beverly Park were beaten on the dock before being placed in automobiles for deportation, but on cross-examination he admitted that one of the deputies got in a mix-up and was beaten by a brother deputy. The sheriff stated that he took one man out to Beverly Park in a roadster, and had then returned to Everett to attend a dance given by the Elks’ lodge.

In relating the events on November 5th, McRae’s story did not differ materially from that of the witnesses who had already testified. He stated that a bullet passed thru his foot, striking the heel of his shoe, and coming out of the side. The shoe was then offered in evidence. He testified that another shot struck the calf of his leg and passed completely thru the limb. Both these wounds were from the rear. His entire suit was offered in evidence. The coat had nine bullet holes in it, yet McRae was not injured at all in the upper portion of his body! The sheriff stated that he fired twenty shots in all, and was then removed to the Sister’s Hospital while the shooting was still in progress.

McRae then identified Ed Roth, James Kelly and Thomas H. Tracy as three of the I. W. W. men who were most active in firing from the Verona. In his identification of Tracy, McRae stated that the defendant was in the second or third cabin window aft the door, and was hanging out of the window

168

with his breast against the sill and his elbow on the ledge. Vanderveer then placed himself in the position described by the sheriff and requested McRae to assume the same attitude he was in at the time he saw Tracy. Upon doing this it was apparent that the edge of the window sill would have cut off all view of Tracy’s face from the sheriff, so McRae endeavored to alter his testimony to make it appear that Tracy’s face was a foot or more inside the cabin window. This was the first identification of Tracy or other men on the boat that was attempted by the prosecution.

The sheriff stated that there were only twenty or twenty-five armed men on the Verona, and he admitted, before he left the stand, that he had told Attorney Vanderveer it was a pity that the spring line on the Verona did not break when the boat tilted so as to drown all the I. W. W.’s in the Bay.

Charles Auspos, alias Charles Austin, followed McRae as the state’s witness second in importance only to the ex-sheriff. The testimony of these two was relied upon for a conviction.

Just why Auspos joined the I. W. W. will never be known, but his claim was that he could not work in the Dakota harvest fields or ride on the freight trains without an I. W. W. card. He was asked:

“When you did line up, you were then willingly a member, were you?”

“Yes sir.”

“And you did not go to Yakima and come back to Seattle to fight for free speech because you were compelled to do so?” asked Moore.

“No,” replied Auspos, “there was no compulsion.”

169

Arrival of the "Verona" at Seattle

Auspos stated that he was willing to take a chance in the fight for free speech and that the worst he expected was something similar to the happenings at Beverly Park. That he was not so willing in his testimony was shown by the uneasy actions of the prosecution lawyers, who moved from place to place around the court room during the examination

170

of this witness, with the view of having him look one of them in the eyes at all times during his recital. At one time Black nearly climbed into the jury box, while Cooley fidgeted in his chair placed directly in the middle of the aisle, and Veitch stood back of the court clerk on the opposite side of the court room, trying to engage the attention of the hesitating witness.

The testimony was to the effect that Auspos had reached Seattle on Saturday, November 4th, and had slept in the I. W. W. hall that night. Next morning at about eleven o’clock he returned from breakfast and was again admitted with examination for a membership card. A meeting was in progress in the gymnasium but was too crowded for him to be able to get in. There was no secrecy, however, just as there was no oath of fealty demanded of a worker upon joining the organization. The witness claimed that he and one of the defendants, J. E. Houlihan, were standing together in the hall when “Red” Doran called Houlihan aside into the gymnasium. Two minutes later Houlihan returned and said, “I made it.” “What did you get?” Auspos declared he then asked his partner, receiving the reply, “A thirty-eight.” Auspos claimed he saw Earl Osborne cleaning a gun in the gymnasium that same morning, and there was a rifle or shotgun in a canvas case in one corner. He said that men were breaking up chairs to obtain legs as clubs and that he, with others, was furnished with a little package of red pepper.

Regarding his actions upon the Verona the witness stated that he and James Hadley came up the steps from the freight deck to the passenger deck just as the boat was nosing against the dock and that he walked across the deck to a point within three feet of the rail. His description of the motion of McRae’s hands differed from that given by the deputy witnesses and was such as would indicate the drawing of a gun from a belt holster. He testified that McRae swung around to the right just

171

before being shot, thus contradicting McRae, who had declared that the turn he had made was to the left. The witness in a rather indefinite manner stated that the first shot came from the boat. All the damaging claims in the testimony of Auspos were severely shaken by the cross-examination conducted by Moore, and Auspos finally admitted that the only point on which he wished to have his evidence differ from the statement he had made to Vanderveer prior to the trial was in the matter of the firing of the first shot. Auspos made no attempt to identify anyone on the boat as having a firearm.

During the examination some reference was made to “Red” Downs, at which Judge Ronald remarked:

“I am a little confused. Did he say ‘Red’ Downs or ‘Red’ Doran?”

“There are two of them,” responded Moore.

“Lots of red in this organization,” cut in prosecutor Cooley, amid laughter from the spectators.

Attorney Moore brought from Auspos the admission that the plea of “Not Guilty” was a true one and he still believed that he and the other prisoners were not guilty of any crime. Yet such are the peculiarities of the legal game that an innocent man can turn state’s evidence upon his innocent associates.

After uncovering the previous record of Auspos, he was asked about his “confession” as follows:

“Mr. McLaren and you had reached an understanding in your talk before Mr. Cooley came?”

“Yes sir.”

“The question of what you are to get in connection with your testimony here has not as yet been definitely decided?”

“I am going to get out of the country.”

“You are not going to get a trip to Honolulu?” asked Moore with a smile as he concluded the cross-examination of Auspos.

“No sir,” stammered the tool of the prosecution unconvincingly.

172

It was at this point that the prosecution introduced several additional leaflets and pamphlets issued by the I. W. W. Publishing Bureau, the principal reason being to allow them to appeal to the patriotism of the jury by referring to Herve’s pamphlet, “Patriotism and the Worker,” and Smith’s leaflet, “War and the Workers.”

The next witness after Auspos was Leo Wagner, another poor purchase on the part of the prosecution. He merely testified that a man on the Calista had said that the men were armed and were not going to stand for being beaten up. Objection was made to the manner in which Cooley led the witness with his questions, and when Cooley stated that it was necessary to refresh the memory of the witness, Vanderveer replied that the witness had been endorsed but a few days before and his recollection should not be so very stale.

When this witness was asked what he was paid for his testimony he squirmed and hesitated until the court demanded an answer, whereupon he said:

“I got enough to live on for a while.”

William H. Bridge, deputy sheriff and Snohomish county jailer, was the next witness. He stated on his direct examination that the first shot came from the second or third window back from the door on the upper cabin. Black asked Bridge:

“How do you know there was a shot from that place?”

“Because I saw a man reach out thru the window and shoot with a revolver.”

“In what position was he when shooting?”

“Well, I could see his hand and a part of his arm and a part of his body and face.”

“Who was the man, if you know?”

“Well, to the best of my judgement, it was the defendant, Thomas H. Tracy.”

Under Vanderveer’s cross-examination this witness was made to place the model of the Verona with its stern at the same angle as it had been at the time of the shooting. The witness was then asked

173

to assume the same position he had been in at the time he said he had seen Tracy. The impossibility of having seen the face of a man firing from any of the cabin windows was thus demonstrated to the jury.

Then to clinch the idea that the identification was simply so much perjury, Vanderveer introduced into evidence the stenographic report of the coroner’s inquest held over Jefferson Beard in which the witness, Bridge, had sworn that the first shot came from an open space just beneath the pilot house and had further testified that he could not recognize the person who was doing the firing.

Walter H. Smith, a scab shingle weaver, and deputy on the dock, followed with a claim to have recognized Tracy as one of the men who was shooting from the Verona. He also stated that he could identify another man who was shooting from the forward deck. He was handed a number of photographs and failed to find the man he was looking for. Instead he indicated one of the photographs and said that it was Tracy. Vanderveer immediately seized the picture and offered it in evidence.

“I made a mistake there,” remarked Smith.

“I know you did,” responded Vanderveer, “and I want the jury to know it.”

The witness had picked out a photograph of John Downs and identified it as the defendant.

The prosecution then called S. A. Mann, who had been police judge in Spokane, Wash., from 1908 into 1911, and questioned him in regard to the Spokane Free Speech fight and the death of Chief of Police John Sullivan. Here attorney Fred Moore was on familiar ground, having acted for the I. W. W. during the time of that trouble. Moore developed the fact that there had been several thousand arrests with not a single instance of resistance or violence on the part of the I. W. W., not a weapon found

174

on any of their persons, and no incendiary fires during the entire fight. He further confounded the prosecution by having Judge Mann admit that in the Spokane fight a prisoner arrested on a city charge was always lodged in the city jail and one arrested on a county charge was always placed in the county jail—a condition not at all observed in Everett.

Moore also brought out the facts of the death of Chief Sullivan so far as they are known. The witness admitted that Sullivan was charged with abuse of an adopted daughter of Mr. Elliott, a G. A. R. veteran; that desk officer N. V. Pitts charged Sullivan with having forced him to turn over certain Chinese bond money and the Chief resigned his position while under these charges; that the Spokane Press bitterly attacked Sullivan and was sued as a consequence, the Scripps-McRae paper being represented by the law firm of Robertson, Miller and Rosenhaupt, of which Judge Frank C. Robertson was the head; that the Chronicle and Spokesman-Review joined in the attack upon the Chief; and that when Sullivan was dying from a shot in the back the following conversation occurred between himself and the dying man: “I said to him ‘John, who do you suppose did this?’ He says, ‘Judge F. C. Robertson and the Press are responsible for this.’ I said, ‘John, you don’t mean that, you can’t mean it?’ He says, ‘That is the way I feel.'”

Judge Ronald prevented the attorneys from going very deeply into the Spokane affair, saying:

“I am not going to wash Spokane linen here; we have some of our own to wash!”

C. R. Schweitzer, owner of a scab plumbing shop, aged 47, yet grey-haired, brazenly admitted having emptied a shotgun into the unarmed boys on the Verona. It was the missiles from the brand-new shotgun—probably furnished by Dave Oswald—that riddled the pilot house and wounded many of the men who fell to the deck when the Verona

175

tilted. Schweitzer fired from a safe position behind the Klatawa slip. Why the prosecution used him as a witness is a mystery.

W. A. Taro, Everett Fire Chief, testified regarding the few incendiary fires that had occurred in Everett during the year 1916, but failed to connect them with the I. W. W. in any way. D. Daniels, Everett police officer, testified to a phosphorous fire which did no damage and was in no way connected with the I. W. W.

Mrs. Jennie B. Ames, the only woman witness called by the prosecution, testified that Mrs. Frennette was on the inclined walk at the Great Northern Depot, at a point overlooking the dock, and was armed with a revolver at the time the Verona trouble was on. Police officer J. E. Moline also swore to the same thing, but was badly tangled when confronted with his own evidence given at the preliminary hearing of Mrs. Frennette on December 6th, 1916.

Never was there a cad but who wished himself proclaimed as a gentleman; never a bedraggled and maudlin harlot but who wanted the world to know that she was a perfect lady. The last witness to be called by the prosecution was John Hogan—”Honest” John Hogan if prosecutor Lloyd Black was to be credited.

“Honest” John Hogan was a young red-headed regular deputy sheriff, who was a participant in the outrage on the City Dock on November 5th. “Honest” John Hogan claimed to have seen the defendant, Thomas Tracy, firing a revolver from one of the forward cabin windows. “Honest” John Hogan had the same difficulty as the other “identifying” witnesses when he also was asked to state whether it was possible to see a man firing from a cabin window when the stern of the boat was out and the witness in his specified position on the dock. “Honest”

176

John Hogan was sure it was Tracy that he saw because the man had a week’s growth of whiskers on his face.

And this ended the case for the prosecution.

As had been predicted there were hundreds of witnesses who were endorsed and not called, and almost without an exception those who testified were parties who had a very direct interest in seeing that a conviction was secured. But thru the clever work of the lawyers for the defense what was meant to have been a prosecution of the I. W. W. was turned into an extremely poor defense of the deputies and their program of “law and order.” From the state’s witnesses the defense had developed nearly the whole outline and many of the details of its side of the case.

When the state rested its case, Tracy leaned over to the defense lawyers and, with a smile on his face, said:

“I’d be willing to let the case go to the jury right now.”